Mastering The Art Of Photographic Composition – Part Three

Where Is Your Center On Interest

With an understanding of our frame, about what we put around our photograph, we can now look at composition more specifically.

Composition is the arrangement of elements in a photograph. Some elements are more important than others and the important ones can be considered as ‘centres of interest’.

Most photographs have a centre of interest whether we intend it to or not. A centre of interest is just that, a part of the photograph that is of particular interest, whether it is to us as the photographer, or to the viewer.

Very often if not most of the time, the centre of interest is our subject (say, a person), or more specifically, it might be the eye a person or the peak of a mountain that is our subject.

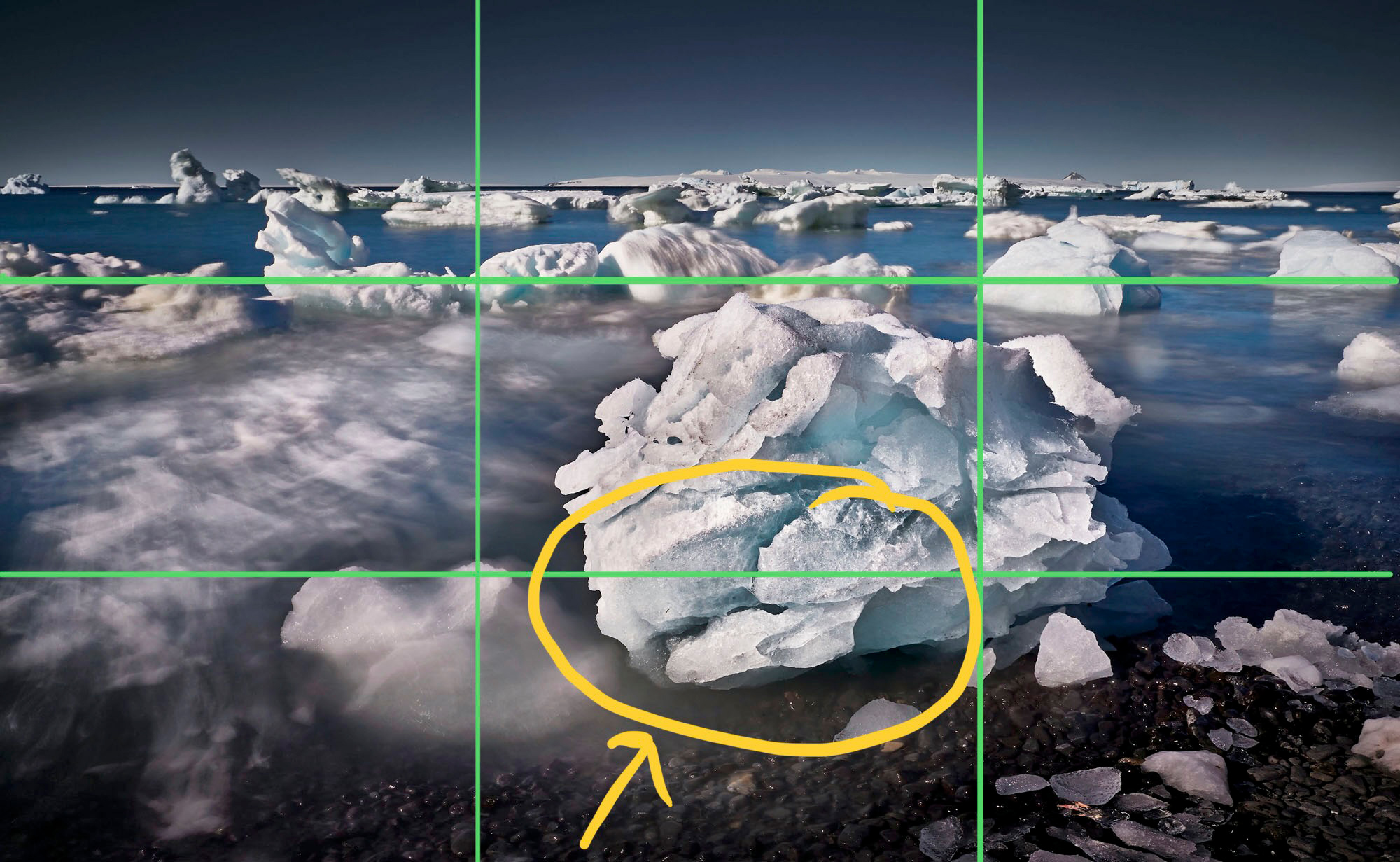

Compositionally, the centre of interest should be the most important element within the frame. For instance, it could be a single tree in a forest of trees, a person running along a beach, or a car falling off a precipice.

Generally, centres of interest are only a small part of the frame and are used to balance the surrounding area. And there can be more than one centre of interest in a photograph.

So why are centres of interest important?

Compositionally, this is where our viewers’ eyes go. They look around a photograph and generally settle on a centre of interest. As photographers, it’s our job to ensure our viewers look at what we consider is the centre of interest.

For instance, there might be an interesting tree in a landscape. One way to ensure the viewers only look at this tree is to eliminate everything else from the photograph. This is where framing and viewpoint are so important because they can help you isolate your subject and create a centre of interest.

Unfortunately, this isn’t always possible. For instance, because of the tree’s location or possibly our viewpoint, we could be forced to include other ‘compositional elements’ such as more trees, shrubs or rocks. These other elements can fight for attention with the tree, so if we can’t eliminate them from the scene (or we don’t want to), we might have to use other techniques such as lighting, focus or post-production processing.

We can also use the position of our subject within the frame.

Composition revolves around the centre of interest and where we place it within the frame can influence what our viewers think about it.

Don’t forget if you are a Silver or Gold member you can click on an image and see it larger

When our subject is positioned in the centre of the frame, it is considered to be very strong, but also static and a little boring.

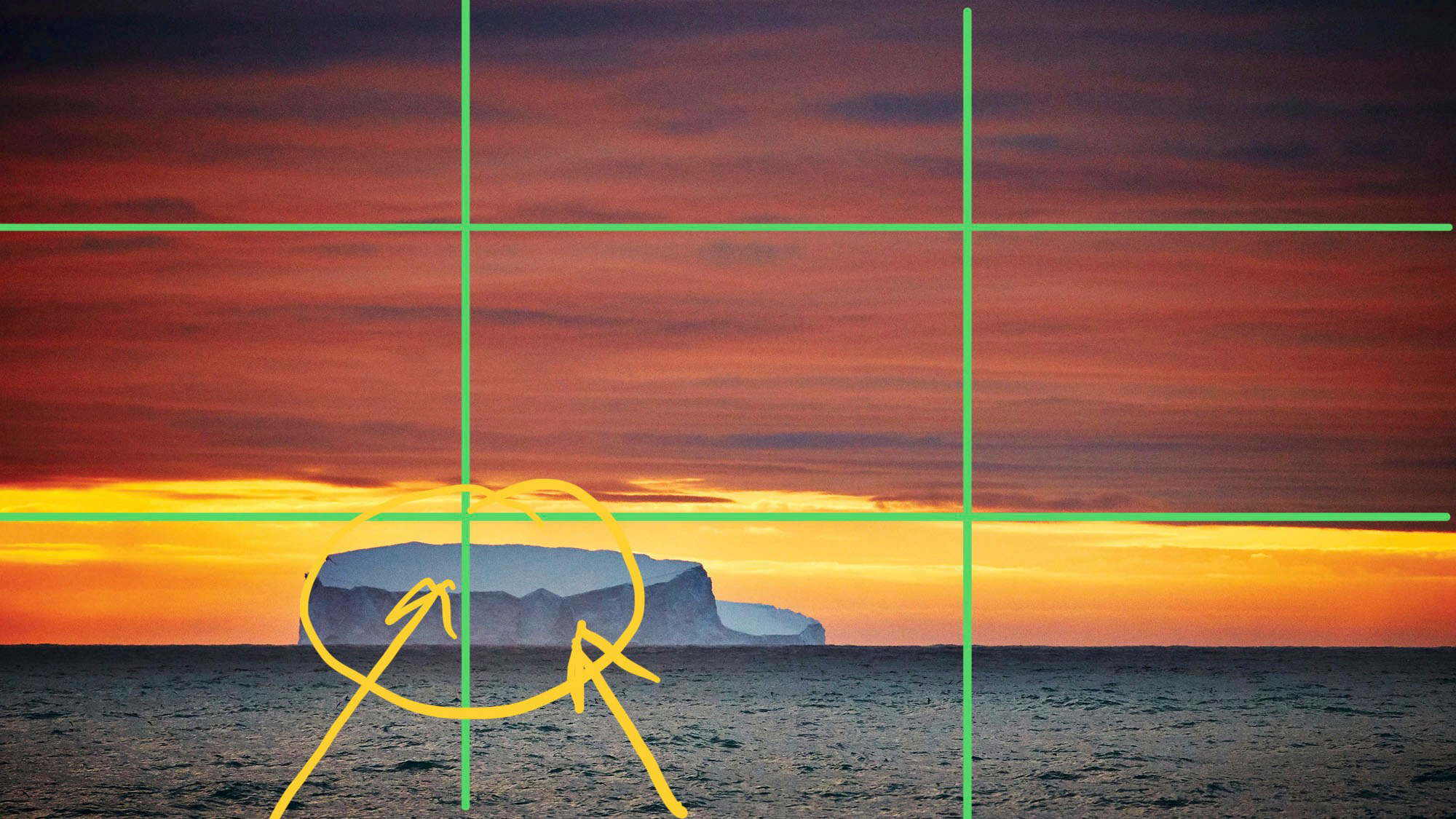

If you position the centre of interest to the side, it is more dynamic and can suggest movement.

Think about where you usually place your centre of interest. Most photographers place it in the middle and this is quite logical because generally we also focus on the centre of interest. Since autofocus cameras have the focusing points in the middle of the viewfinder (or at least, this is the default position), guess where most photographers leave their centre of interest after focusing?

Sometimes, the middle of the frame is exactly the right position, but not always.

If you’re putting your subject in the middle of the frame simply because it’s easy to do so, you’re putting it there for the wrong reason.

Another position might make a much stronger, more interesting photograph.

The small tree and patches of sunlight are competing centres of interest. The darker and plain background (in the shadow) helps the tree stand out compositionally. The sunlit tree is the centre of interest, along with the strip of sunlit grass to the right. This strip of sunlight is a centre of no interest and will be cropped out!

What Is The Rule Of Thirds

Once you’ve determined your centre of interest, exactly where should you place it in the frame?

The centre of the photograph, as discussed already, is not always the best position; somewhere off to the side is generally better, but not too close to the edge of the frame.

Many photographers use the Rule of Thirds to help with composition and as long as you remember that rules are meant to be broken, it’s not a bad starting point.

The Rule of Thirds is loosely related to the Golden Mean, a classical ratio used by the Ancient Greeks and also found occurring in Nature.

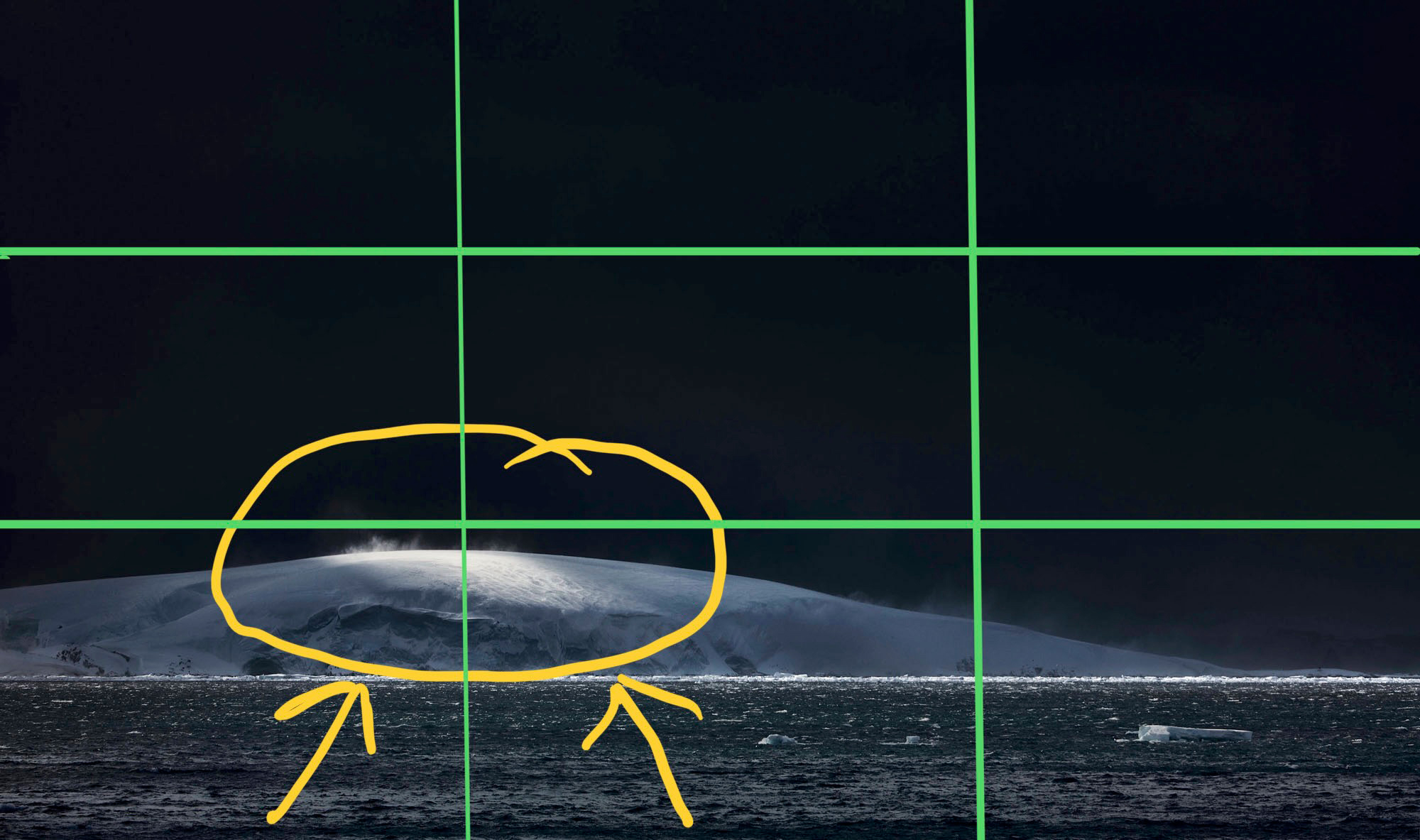

However, the Rule of Thirds is a little simpler to calculate and suggests you divide the frame into three sections, first horizontally and again vertically. You position your centre of interest roughly where the lines intersect, so this gives you four options.

Some cameras even overlay a grid in the viewfinder to help you compose better photographs, but don’t be too precise in your positioning. Your centre of interest needn’t be exactly on the intersecting lines – near enough is often good enough.

You also don’t want to position your subject on this grid if it means adversely changing your framing. There’s no point including a rubbish bin in the side of your image, just to get your centre of interest in the right place. Better to first omit the rubbish bin, then get the best compromise possible for your centre of interest.

There are a lot of photographs where the Rule of Thirds simply won’t work, because of the size or shape of your main subject. However, there are other compositional devices, such as lines and shapes, which can be directed along the Rule of Thirds to strengthen composition.

For most people, working out how to use composition requires experience. With experience, you look at lots of different photographs and paintings, and you assess them. Eventually you have a feeling for what works, and what doesn’t.

Some researchers have delved into the mathematics and geometry behind composition and although helpful, for every image that proves the rules, there seems to be at least another that breaks the same rules.

Composition is a difficult thing to teach because it depends in part on aesthetics, on culture and even fashion.

For instance, in a country where the script is read from right to left, composition is often considered stronger when it’s opposite to what we in Australia would consider best, because we read from left to right! So, what works in one culture might be less effective in another.

Nevertheless, although composition can be difficult to pin down, there’s no doubt an understanding and appreciation of the issues involved makes a big difference!

Using The Rule Of Thirds

Peter Eastway

May 2022

Sydney, New South Wales

Peter Eastway is an Australian photographer known internationally for his landscape photography and creative use of post-production. He has been involved in photo magazine publishing for over 30 years, establishing his Australia's Better Photography Magazine, in 1995. As a result, Peter and his websites are a wealth of information on how to capture, edit and print, offering tutorials, videos and inspiration for amateur and professional photographers. Peter was the author of the Lonely Planet’s Guide to Landscape Photography. His photography has featured on the cover of the Lonely Planet’s guide to Australia, in articles in the Qantas inflight magazine, and in an international Apple television commercial. And he has worked with Phase One researching and promoting its high-end medium format cameras and Capture One raw processing software. He has also published The New Tradition, an anthology of 100 award winning images with accompanying techniques and discussions. He was one of the featured photographer in the first Tales By Light television series aired on the National Geographic Channel in Australia and produced in partnership with Canon Australia. It can currently be viewed on Netflix around the world. Peter Eastway is a Grand Master of Photography, a Fellow and an Honorary Fellow of the Australian Institute of Professional Photography, and a Master and Honorary Fellow of the New Zealand Institute of Professional Photography. He won the 1996 and 1998 AIPP Australian Professional Photographer of the Year Award. He is a WPPI Master of Photography. He was more recently the 2019 AIPP NSW Epson Professional Photographer of the Year (Australia). Peter is just over 60, rides a short surfboard, believes two skis are better than one, and in case you're buying him lunch, he is vegetarian.