Photographing Is Nothing – Looking Is Everything

Henri Cartier-Bresson, arguably the most influential photographer of the twentieth century, said: “Photographing is nothing. Looking is everything.” This is a very wise statement that a lot of people ignore.

Photographers tend to get wrapped around the axle on equipment, which is understandable when you consider the complexity and capability of modern digital cameras. But the equipment has almost nothing to do with good photography. Looking has a great deal to do with it: looking and recognizing what you’re feeling as you look.

To put it another way, successful visual art, especially great visual art, depends on the artist being able to bring out something beyond the mere beauty or literal meaning of a scene. Something transcendental. Something beyond the scene’s empirical significance. Something spiritual. Two examples of this are John Constable’s “The Hay Wain,” which also happens to be visually beautiful, and Edward Hopper’s “Nighthawks,” which doesn’t. Both leave you with something that goes beyond the image itself.

When it comes to transcendental significance an advantage painting has over photography is that a painting doesn’t have to be an accurate image of reality. “Nighthawks” is simplified drastically. There’s no random trash on the street outside the diner, for instance. You’re on a darkened street, and you’re looking through a large window into an all-night diner. You see an interaction between two customers at the counter and the server. There’s also a mysterious third customer concentrating on something we can’t see. There’s a feeling from the painting that I can’t identify or describe. I think that if I could describe it the painting wouldn’t have such a powerful effect. It’s probably Hopper’s most recognized work.

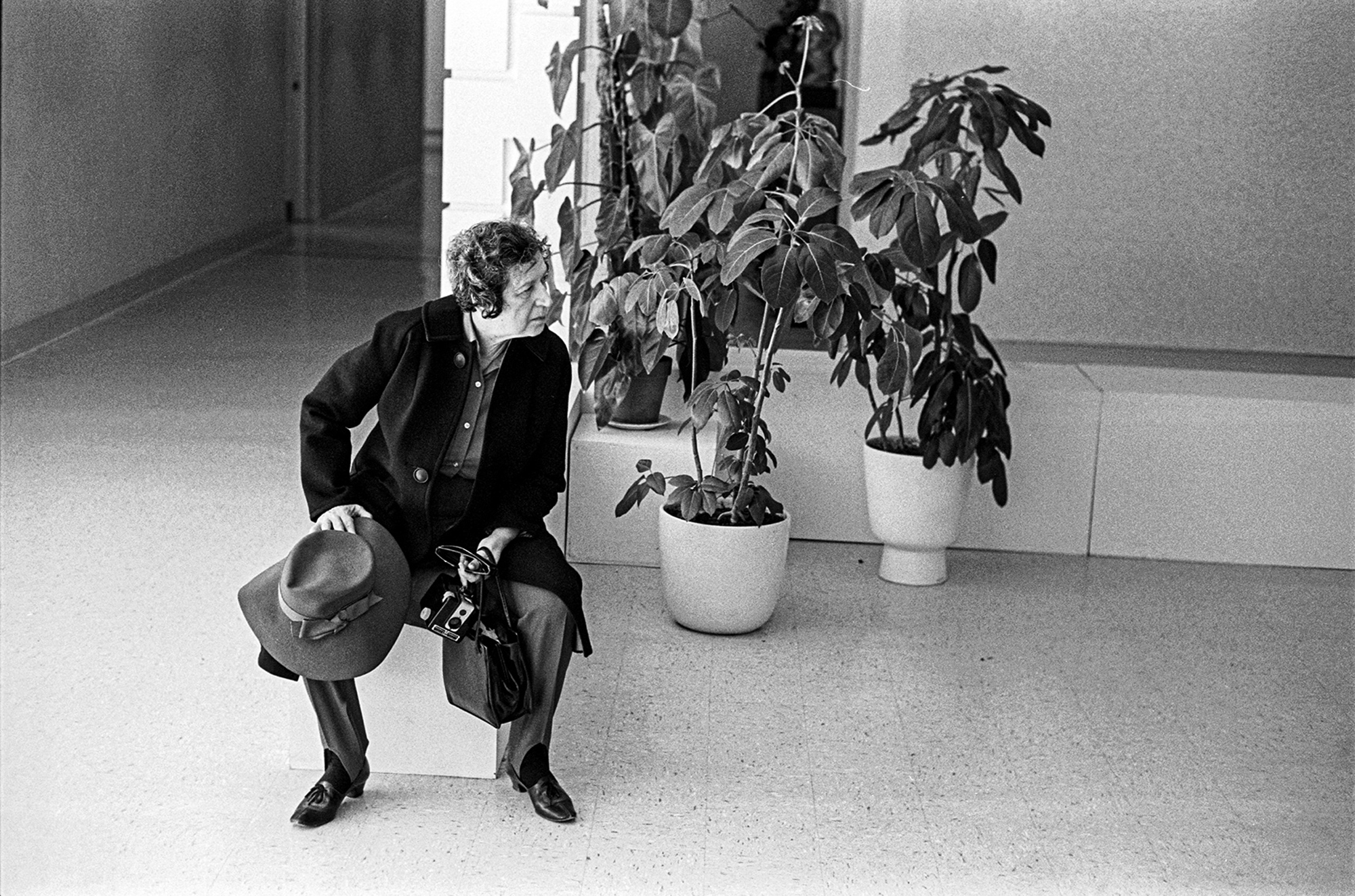

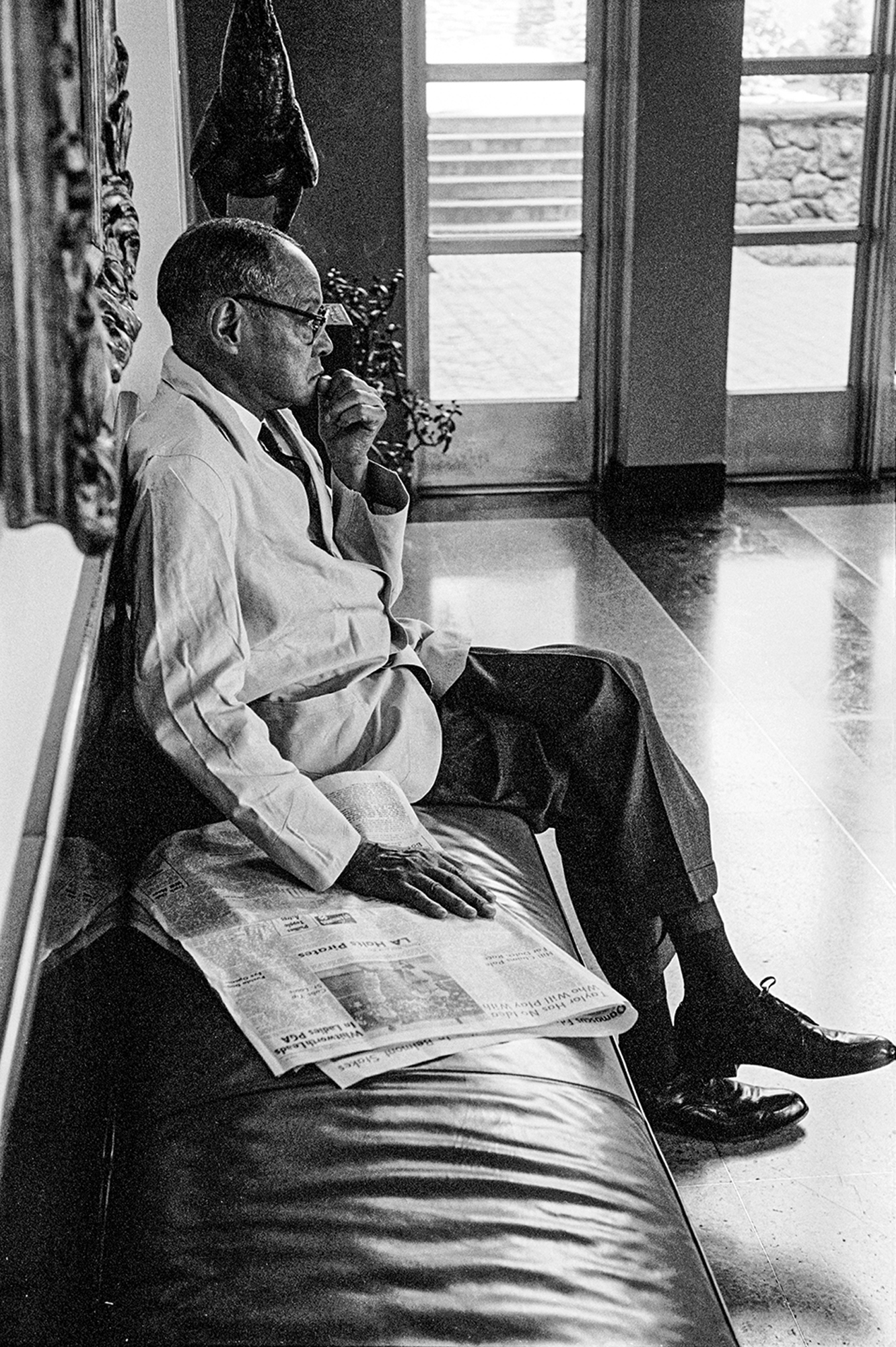

On the other hand a photograph such as Garry Winogrand’s “Los Angeles 1969” brings objectivity to the fore in a more powerful way than can a painting. A crippled young man in a wheelchair is being passed on the sidewalk by three pretty girls. The message is obvious, but there’s something more powerful in that image than its simplistic message. The scene is haunting. Once you see it you can’t shake off the echoes the picture leaves in your mind.

Social networking sites such as Facebook are full of photographers attempting to sell their products. The products are almost always landscapes. After all, a landscape stays still and doesn’t complain if it catches you shooting its picture. Furthermore, a well-done landscape can be quite beautiful. Unfortunately, an ordinary landscape doesn’t echo in your mind the way “The Hay Wain,” with its comfortable-looking cabin and two people crossing the stream in the flat wagon does. Nor does it hang around in your mind the way “Nighthawks” does. Nor does it grab you the way Winogrand’s photograph does.

Ansel Adams, primarily a landscape photographer, was wildly successful. Why not me? There’s a beautiful landscape right outside my window. All I have to do is go out with a really good digital camera and bang away. I suspect something like that crosses the minds of the landscape photographers I see on the web. After all, with today’s equipment, you can do the things Ansel did without a lot of pain and strain in a stinky darkroom.

Ansel’s success wasn’t built on technology though he was a very competent technologist. He and Fred Archer developed the “Zone System,” which in film days could give your negative a near-perfect brightness range if you were willing to take a few light-meter readings and do some arithmetic. The result was more or less the equivalent of what Adobe’s Camera Raw gives you with a single click.

Ansel’s success was built on his ability to look and see, not on the quality of his equipment or his post-processing skill. Many of his photographs, especially, in my estimation, “Moonrise Hernandez” contain something that goes far beyond the literal scene. Ansel was driving home from a New Mexico shoot when he saw what the evening light was doing in Hernandez, a little town next to the road. He slammed on the brakes, hauled his camera and tripod to the platform on top of his van, and made the shot. His technical expertise came into play when he realized he didn’t have his light meter and didn’t have time to climb down and get it. He “guessed” at the exposure, though his was a very well-educated guess. It’s true that Ansel did some major post-processing on “Moonrise,” but the picture with its transcendental significance was there once he clicked the shutter.

There are a couple of reasons why landscape photographs I see offered on the web may not sell well.

First, there’s today’s ease in making technically excellent photographs. You don’t need a darkroom, and thanks to products like Adobe and DxO, extensive post-processing is doable, even relatively easy, without a lot of expensive physical equipment. In-Camera Raw It’s easy to adjust things like brightness range and color saturation. You can shoot birds on the wing using almost unbelievably high shutter speeds and apertures, and DxO’s PhotoLab or PureRaw can remove the distracting noise introduced by ultra-high ISOs.

But all these miracles are available to your next-door neighbor. Your neighbor can step outside and shoot that lovely landscape just as you can. He doesn’t need to buy it from you.

Then there’s the problem that many landscapes offered for sale on the web are indistinguishable from the ones down the page. Landscape shooters have a tendency to go for pretty rather than transcendental. There’s a lot of pretty out there: sunsets, sunrises, waves against the shore, snowy winter scenes, etc., etc., etc.

So how do you learn to produce photographs with at least a modicum of Transcendentalism, which “WordWeb” defines as “Any system of philosophy emphasizing the intuitive and spiritual above the empirical and material.”

Learning about the rule of thirds won’t help much. One thing that might help is looking at images that have stood the test of time. You might go back to the first Impressionist exhibition, held in Nadar’s photographic studio, since the Salon wouldn’t accept the Impressionists’ paintings. Many of the paintings in the salon have been forgotten. The Impressionists’ paintings haven’t. Another thing worth doing is becoming thoroughly familiar with Edward Hopper’s work and the Impressionists’ work. In the world of photography, Henri Cartier-Bresson is worth extensive study, as are Garry Winogrand, Robert Frank, and Ansel Adams.

What you’re looking for isn’t just beauty or a well-told story but something that gives you an experience beyond beauty and empiricism. Once you find images that give you that experience – and you won’t find many of them – you’re ready to grab your camera and go out looking for that same kind of experience in real life. The search can be exhausting and disappointing. First, you won’t find many scenes in real life that give you that kind of experience. Second, you’ll flub a lot of shots. The kind of thing you’re looking for often lasts no more than a few seconds.

So when you’re out looking, always be ready mentally to slam on the brakes and shoot the picture. With the equipment we have today, you don’t need to haul a tripod to the top of the car, and the light meter is already in the camera. Nowadays, it’s even more true that photographing is nothing. But looking hasn’t become any easier.

Russ Lewis

December 2022

Leesburg, FL

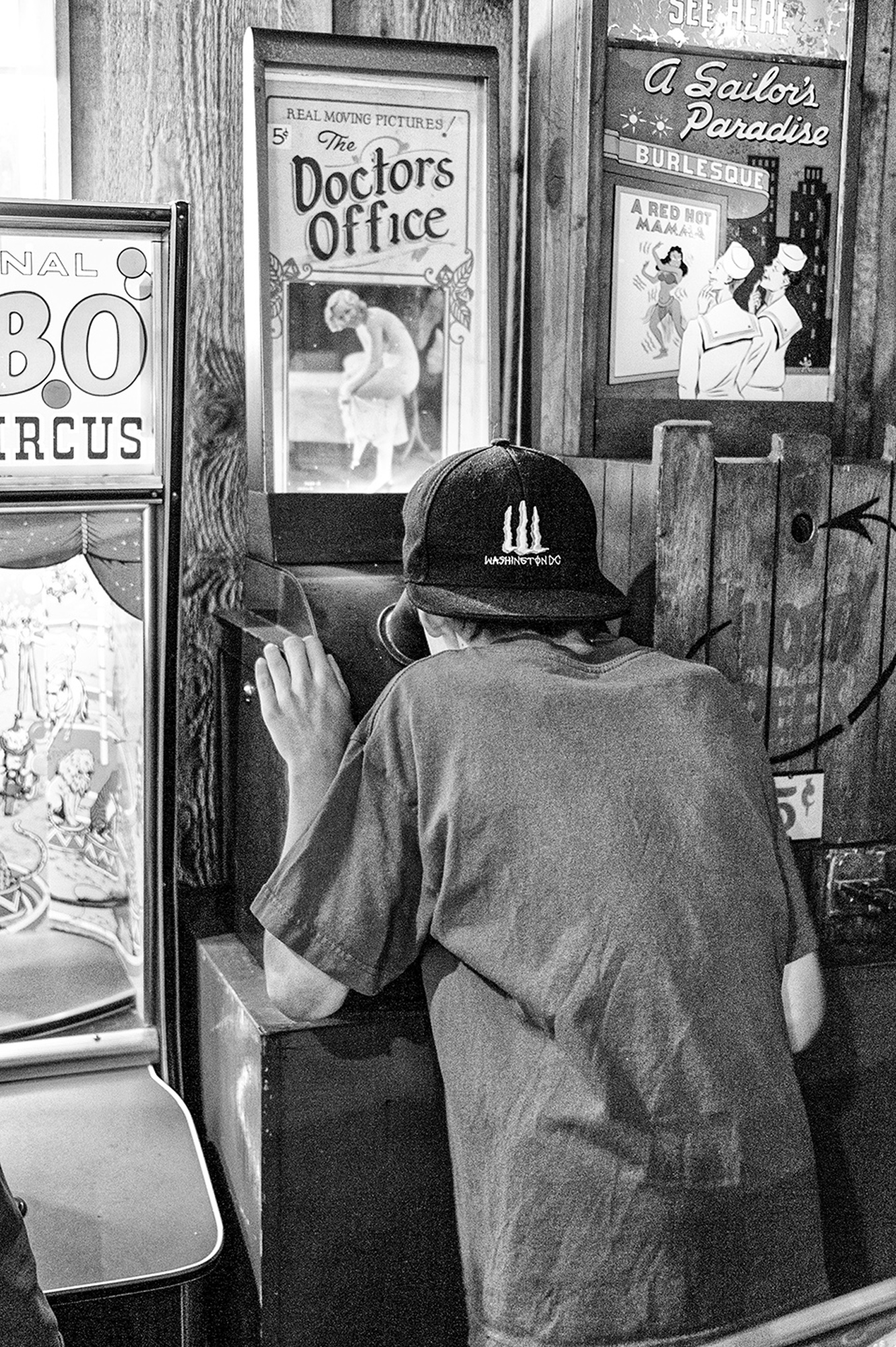

I'm now 92. I spent 26 years in the United States Air Force. Flew fighter-bombers in Korea and was there when the war ended. Ten years later I was commander of a radar site in the Mekong delta. Nine years after that I was commander of the group that contained all the radar sites left in Southeast Asia during the Cambodian operation. I was there when that one ended. After I retired from the Air Force I began doing software engineering, and did that for another thirty years. I became a photographer at 13 when I built a darkroom in my parents' fruit cellar. When the war ended in Korea I started going downtown in Taegu, shooting pictures mostly of people. I was doing street photography, though I didn't know it at the time. Street has been my favorite thing ever since. You can see it all on my web site. russ-lewis.com.