Pattern Emergence In A Complex Agricultural Ecosystem

An Opportunity for Monochrome Photography

By Anders Vinberg and Chris Cluett

The Palouse is a geographic region of approximately 19,000 sq. miles of farmland primarily located in the southeastern portion of Washington State. Since the late 19th century, the Palouse has been a major wheat producer, along with other grains. The characteristic rolling hills were formed since the ice age from windblown dust and silt called “loess.”

The Palouse experiences an annual agricultural lifecycle composed of four components: winter dormancy, spring emergence, summer growth exuberance, and fall maturity. The Palouse has been “discovered” by photographers who flock there primarily during the colorful summer growth and fall harvest periods. We begin this article with our only color image to give a sense of what the area looked like during early spring.

tilled soil; natural and manmade lines and shapes document the early spring Palouse landscape.

We decided to visit the Palouse for a week in mid-April, and during our time there we did not encounter a single other photographer. While we were unsure what the conditions would be at that time, we were hoping to capture the earliest manifestations of this year’s wheat cycle, including tilling and preparing the soil, planting, and early emergence of a new crop. Our intent was to concentrate our efforts on monochrome imagery.

Why Monochrome?

Just as emergence theory addresses pattern recognition in complex systems, we were interested in discovering and emphasizing the abstract and artful patterns in the Palouse ecosystem, including lines, textures, shapes, and tones in both the natural and manmade landscape. This early spring period could also be described in terms of the emergence of color. Monochrome allowed us to concentrate on the foundation that forms the canvas on which the new growth and colors will be painted.

We are interested both in artistically pleasing compositions and in the story the Palouse can tell us about the place and the people who farm it through a better understanding of its foundational elements as revealed to us in black and white early in the crop cycle.

the artistic patterns created by the farming of the soil.

The farming machinery draws regular patterns over the rolling hills, guided by computers, GPS, and 3-D modeling. But viewed from ground level, at sharp angles, the patterns form intriguing abstractions that do not look utilitarian at all. The strong contrasts in the soil and crops enhance the artistry.

without being held to journalistic or scientific standards.

creating a graceful curve.

creating a mysterious echo.

but viewing at a slant suggested the farmers have hidden artistic goals and talents.

Living in the Palouse

The Palouse has a fascinating story to tell throughout the seasons of the year, and that story begins in the spring where last year’s crop must be tilled into the soil to prepare for planting the new crop.

We spoke with one farmer who had just burned off last year’s stubble and weeds, leaving black ash on his fields. He said he leases the 9,000 acres that he farms. The investment of time, skill, and effort on the part of the Palouse farmers is extraordinary.

The winds that created these fertile soils tens of thousands of years ago continue to blow today and further shape the landscape. While we were there it was quite windy, creating dust devils and blowing great plumes of dry topsoil during the tilling of the land.

We were struck by the vastness of these farms and the amount of effort it must take to keep them productive. In addition, we wondered how these farmers adapt, working out alone in this vast landscape.

We may look at farming the Palouse as a lonely lifestyle, but these farmers have been working this land with dedication and passion for generations. They farm with precision and efficiency, and the patterns etched in the landscape are works of art, all nicely documented in monochrome imagery.

Historical Perspective

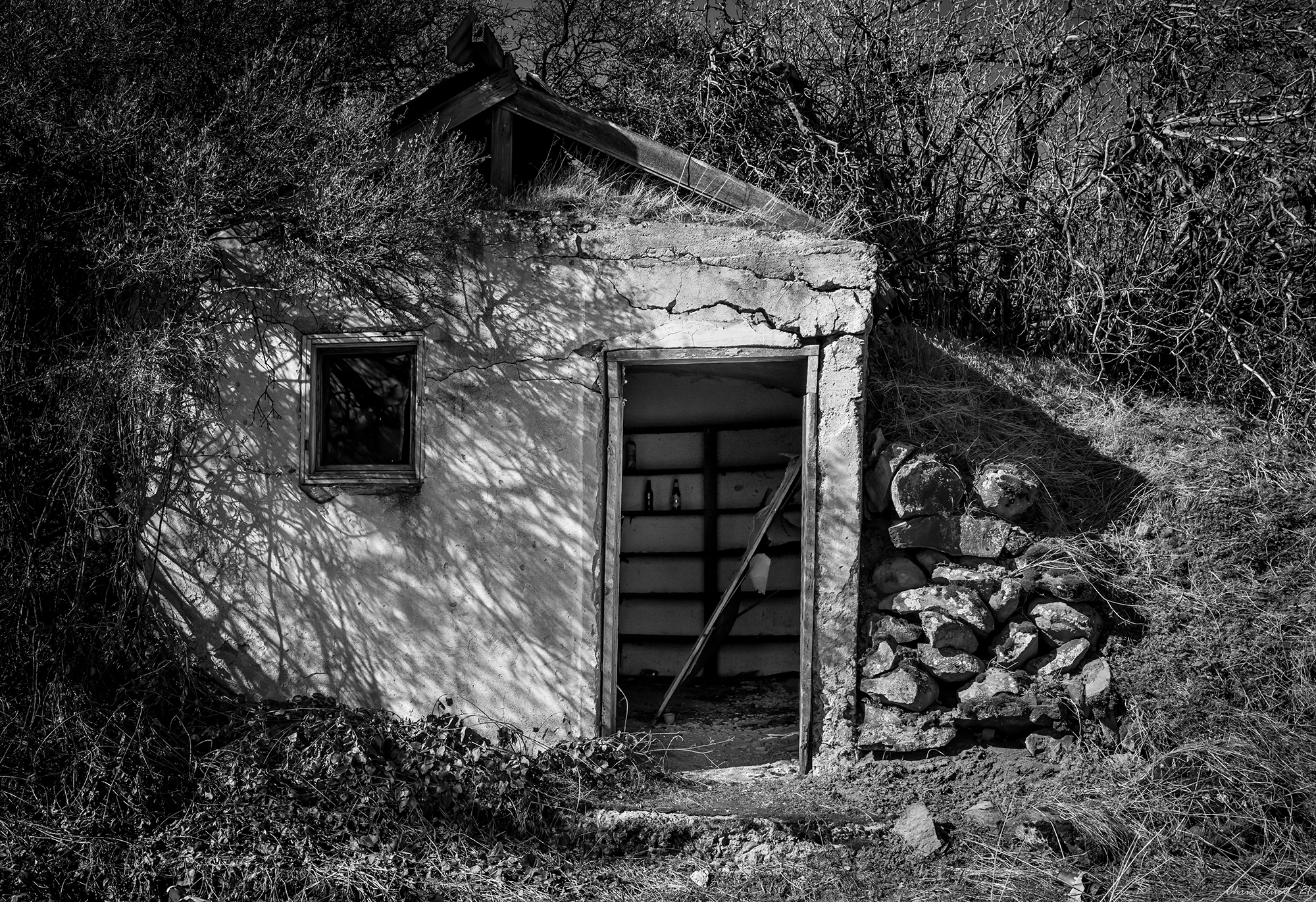

Evidence of their long presence is readily identifiable in the old barns, vehicles, and farm machinery scattered throughout the landscape, a popular subject matter for photographers. Monochrome images of these human artifacts emphasize the details, shapes, and tones, effectively rendering the weight of history, perhaps no more effectively than color images, but in a striking and impactful way.

Monochrome is particularly effective in communicating imagery in a graphic, artistic way that offers contrasting tones that emphasize important parts of the story, and gradations in tones that help direct the viewer’s eye through the image. The image below of the side of an abandoned barn emphasizes construction details, including joinery and saw kerfs, and then draws the eye to peer through the opening at hints of what might have been stored inside. It leaves us wanting to be able to see and discover more. The image is simple and straightforward, with no extraneous colors to distract the viewer.

a couple of cold ones, then walk out the door one last time never to return?

A Brief Comment On Gear

Images selected for this article were taken with medium format cameras (Hasselblad and Fuji) and with the Leica Q2M dedicated monochrome camera. Each camera and lens combo rendered these monochrome images with remarkable fidelity in raw format and were comfortable to work with.

We primarily used short lenses. The Leica Q2M has a fixed 28 mm lens. It is wonderful in all ways, and the short lens worked well. An orange filter was used on many of the Q2M images to enhance contrast. For the MF cameras, we primarily used 80 and 90 mm lenses, slightly longer than a “normal” lens—with a 0.8 crop factor, they are “field-of-view equivalent” to 64 and 72 mm in full-frame terms. For many of the wider landscape views, we stitched multiple images into panoramas. The dramatic patterns in the landscape often encourage longer lenses, but something about this trip inspired using the shorter lenses, maybe the different appearance in the spring, maybe the monochrome approach — technology, psychology, and art working together in mysterious ways.

In Closing

Against a background of burned-off weeds and stubble in preparation for tilling and planting, we stumbled upon a derelict vehicle partially imbedded in the side of a dirt road. It was full of bullet holes, suggesting a variety of explanations that went unanswered. But it was there, and obviously had been there for some time, adding yet another interesting element in the Palouse mosaic.

We enjoyed our time in the Palouse and feel that our visit in the “off-season” offers a new perspective on the place. While any time of year spent in this beautiful area of the country offers wide-ranging opportunities for photography, we took away a few “lessons learned” from our experience during this early spring season.

- We recognize that each of the main seasons experienced in the Palouse convey something unique about the place and its people, and offer photographers varied opportunities to tell the Palouse story.

- We encourage photographers to be flexible and consider the potential opportunities outside of the “normal” timeframes considered optimal for photographing in various locations.

- We suggest including monochrome imagery, along with color, to highlight the underlying artistic elements in the landscape and its associated constructs.

- Photographers of the Palouse emphasize image capture during the early morning and later evening hours to benefit from the golden hour lighting on the wheat fields and rolling landscape, along with the dramatic shadow effects created by a low sun and clouds. However, looking back on our experience with monochrome during early spring conditions, daylight photography offered advantages in highlighting the lines, shapes, and textures of both the natural and man-made landscapes. This is another example of the value of keeping an open mind about our assumptions.

- One of us had photographed in the Palouse twice before in the summer and the fall. Although we started out with a general sense of the place and some specific locations, we made a point of exploring off the usual routes to discover what we might find. This revealed many photographic opportunities that a more rigid itinerary would have precluded – another advantage of thinking outside the box.

By Chris Cluett and Anders Vinberg

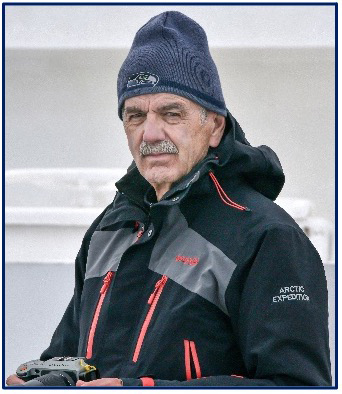

Anders and Chris met on a photo workshop to Greenland arranged by Kevin and Rockhopper. In that international group, by coincidence, they both live in Seattle. And both bought the Leica Q2M the same week!

ANDERS VINBERG

Seattle, Washington

Website: https://andersvinberg.photo

Retired and enjoying photography, so much to learn, so many masters to be inspired by. Medium format is lovely to work with, but so are smaller formats. Mostly monochrome at this time, but a lot of color in the background, including the Palouse.

CHRIS CLUETT

Seattle, Washington

Website: https://clueless.smugmug.com/

Photography is his avocation in retirement, and he has traveled across the globe creating images that reflect landscapes, cultures, and natural and man-made environments. He currently works in MF with an emphasis on monochrome imagery.

Chris Clett and Anders Vinberg

June 2022

Kirkland, WA

Anders is a photography amateur, he does it for the love of it. He is a retired software architect, and tries to avoid letting the computer technology dominate what is supposed to be art. He has a lot to learn, which is good, we should always be learning.