Art and Design – Inspired By David Pye

Design proposes, workmanship disposes.

David Pye

Introduction

2022 marks the beginning of a new series of essays inspired by the writings of David Pye. I am starting this new series because the issues raised in my previous essays lead me to question how I can shake loose from the influence of the artists who came before me. Why is it that I want to copy the work of previous artists instead of creating my own work? Why is this desire so strong as to cancel my own desire to create something original, something entirely ‘me’?

I found answers to these questions in the writings of David Pye which I read during the pandemic while practicing woodworking, one of the hobbies I engaged in during isolation times. Pye is difficult to read because he uses terms to which he attaches a personal meaning, such as regulation, jig, workmanship, design, variety, and more. At first glance, these are commonplace words. However, the meaning Pye attaches to them is markedly different from the one we are used to. This meaning is cryptic because it is explained gradually, over the course of his books, and according to the whim of his reflection. This means that a careful reading of Pye’s books, complemented by detailed research, is necessary to define these terms and understand what Pye means.

Pye’s two most important books are The Nature and Aesthetics of Design and The Nature and Art of Workmanship.

They cover Pye’s two central concepts: design and workmanship. I will explain the meaning Pye gives to these terms as I proceed. However, to keep the organization of this series of essays simple and logical, I decided to write about Design first and about Craftsmanship second. While these two concepts form a dualism that provides opportunities for insightful conclusions, I found it best to introduce each in separate essays before looking at how one plays upon the other.

Before I start, I want to mention that this is not a self-contained essay but the first of a series of essays. As such, it needs to be read like the first chapter of a book because the conclusions I reach will be presented over the course of the series. As of now, there are six essays, however, this number may change because the series is not completed yet. The number of essays is in part due to the necessity of keeping the length of each essay manageable for web publication.

About David Pye

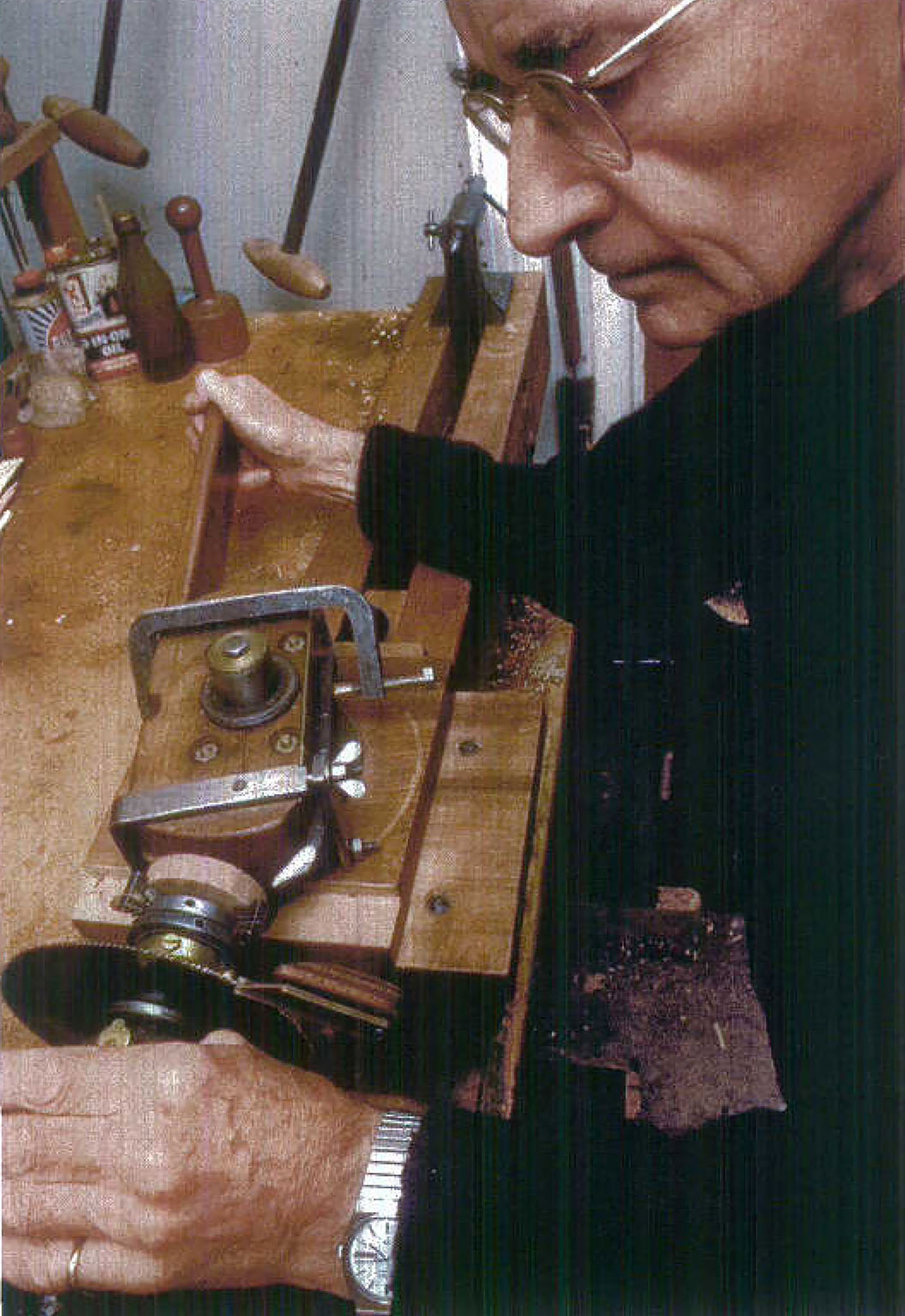

David Pye was a maker of wooden bowls, the teacher of several generations of furniture designers, and one of the most respected British craftsmen. In his time, he was one of the few who wrote about craft in an unsentimental fashion.

Pye studied at the British Architectural Association at the peak of Modernism. He was against the use of concrete in buildings, preferring wooden buildings. Pye’s interest in wood led him to design furniture for industrial production and to carve wooden bowls. In 1950, Pye built what he called ‘the fluting engine’ with which he cut fluting patterns on the inside of his bowls. This machine was in effect a guided hand tool, what Pye would later call a ‘jig’. It embodied the concerns about design and craftmanship expressed in Pye’s writings. His goal was to bring diversity (another of Pye’s cryptic terms) to the object, in this instance the bowl, by enlivening the quality of its surface and by offering the viewer the opportunity to focus on both the general shape of the bowl and the details of its carving.

Pye’s texts are fundamental to understanding the process of designing and constructing items, both by manual and machine processes. Even though Pye writes about design, woodworking, machines, and hand tools, Pye’s writings are philosophical in nature. His books are not instructional texts aimed at teaching design or woodworking. Their purpose is to reflect upon how everyday objects are designed and produced and to analyze the implications of producing these items by hand or with machines.

Pye’s writings are essentially focused on woodworking. However, Pye’s writings bridge the gap across disciplines. His theories and conclusions apply not only to crafts but to fine arts. I applied them to fine art photography by drawing parallels between Pye’s ideas on design and craftsmanship and my reflections on photography and creativity. My main focus is to find out why the work of those who came before me affects my artistic and photographic creativity.

What Is Design?

Looking at the definition of design online brings up traditional definitions such as ‘an outline, sketch, or plan,’ ‘an arrangement of lines or shapes,’ ‘the process of envisioning and planning the creation of objects,’ ‘the specifications for the construction of an object’ or, my favorite because of its minimalism, ‘a plan to make something’.

Pye agrees with these definitions but adds an important stipulation: a design is an ideal form that cannot be translated into a physical object without being altered significantly. Pye adds that a design can also be described verbally, something which does not appear in traditional definitions of the term. For Pye, design is something that can be conveyed with both words and drawings. By comparison, workmanship cannot be described with words and drawings. It can only be described by making. Simply put, design is the idea and workmanship is how the object is created.

For Pye, a design is an ideal form. It is conceivable but not attainable. It is an unrealistic perfection. It cannot be literally translated into a physical object. It needs to be adjusted, adapted, and changed to make it into a real object. This is because a design does not have to take into account the physical reality of the world. Things can be drawn in two dimensions or described with words, that cannot necessarily be physically built as three-dimensional objects. When creating an actual work of art, the artist must take into account the realities of the medium. He must accept that perfection is not possible. This means that differences between the original design and the actual product will exist. The final work of art will be different from the original vision that the artist had. This vision will need to be adapted. It will have to be modified or transformed so that it can become a physical reality.

Designs are therefore Platonic in nature. To make a parallel with Plato’s allegory of the cave, designs are the shadows seen passing in front of the cave, and the three final pieces are the actual objects located outside of the cave. For Pye, the designer is located inside the cave. From there only the contours of objects are visible. This gives the viewer no real clue as to the three-dimensional aspect of the objects passing in front of the cave opening. Presented with only shadows the viewer must imagine what the actual objects look like. Left with minimal clues the viewer is bound to be largely wrong. Freed from the reality of the physical world, the viewer in the cave can imagine things that are vastly different from what they are in reality.

The craftsman, on the other hand, is located outside of the cave. His job is to transform two-dimensional shadows into three-dimensional objects. To do this, the craftsman has to interpret the shadow designs. He has to make changes and concessions. While he is free to use his vision and inspiration, he must contend with the constraints imposed by reality. Unlike in the cave, where shadows were largely open to interpretation, the objects he constructs must abide by the laws of the physical world.

The outcome is a departure from the original design. While the final object retains the general aspect of that design, the work of the craftsman causes inevitable transformations to the drawings of the designer. It modifies in order to make the creation of a three-dimensional object possible.

These differences, this gap between design and craftsmanship, led Pye to say that ‘design proposes and workmanship disposes.’ What Pye meant is that the design of an object, be it a drawing or a verbal description, is a proposition, an idea, a starting point. The creation of the actual physical piece is by definition a departure from the original design. The craftsman will dispose of the proposed design by making changes because he has to contend with the limitations of the physical world. While there are no limits to what can be designed, there are limits to what can be built. The transition from design to craftmanship is the transformation of an idealistic description into a realistic construction.

In industrial practice, the designer and the craftsman are two different individuals. The designer creates the drawing, gives it to the craftsman, and hopes that the workmanship will be as close to the design as possible. However, it is the craftsman who controls the quality of the workmanship. This means that the quality of the finished object depends in large part on the craftsman’s skills.

In artistic practice, things are different because both the design and the workmanship are created by the same person. The artist is both designer and worker because he is both the initiator of the idea and the manufacturer of the final piece.

This means that an artist does not just design an ideal form. He also attempts to turn this ideal form into a physical object that can be touched and felt. This creates two problems. First, the artist has to transform an ideal form into a physical reality, something which by nature is an impossibility. Second, the artist has to decide which level of craftmanship will be used. This decision offers little leeway since in art craftmanship is expected to be of the highest level. This is because artists are not only uncompromising, they are also aware that their artistic creations are the physical embodiment of their artistic mastery. Doing anything less than their very best will be a poor reflection of their personal skills, their personality, and their level of artistic achievement. The bar is therefore set as high as it can be and failure is lurking around the corner, waiting to happen.

Needless to say, the process of artistic creation is filled with stress. It is a journey during which the artist navigates between success and failure as best as he or she can, trying to avoid crashing upon hidden reefs while navigating seas alternately calm and furious, unable to predict when the change from one state to the other will take place.

Design Is Universal

I believe that design is universal. I do not believe that design is limited to creating practical objects such as a car, a piece of furniture, a building, and so on. I believe that as creative individuals we all use design, regardless of the medium we use. We all use design, whether we work with a visual medium such as photography, drawing, or painting. With a written medium, such as fiction or nonfiction. With a representational medium such as theater, dance, or trapeze. Or with any other creative medium.

I, therefore, find it necessary to expand the concept of design to all artistic mediums. When creating a work of art, a design is either an idea in the mind of the artist, a sketch, a verbal description, or a previously created work that the artist uses as inspiration and guidelines. The physical outcome can be a painting, a drawing, a photograph, a book, a theater play, a trapeze act, or any other creative work.

Design And Photography

When I apply Pye’s concept of design to photography, I find that in landscape photography design is a combination of three variables: location, composition, and processing.

During fieldwork, location and composition are what I used to create the design of a photograph. These are the two elements that define the construction of a photograph. They define the where and the how: where a photograph is taken and how the location is depicted.

During studio work, image processing is what I use to complete the design started in the field. Processing the image, be it in the chemical or digital darkroom, is an interpretation of the photograph captured in the field.

Location, composition, and processing are the three major factors of photographic design. However, sub-factors must be taken in consideration.

In regards to location, these sub-factors include the time of day, the time of year, and the weather conditions. As we know, some locations are best at sunset, some at sunrise and some at a specific time of the year because that is when the sunlight creates the most dramatic effect. Where a photograph is taken is not enough to create a specific design. All the variables I just mentioned must be taken into consideration.

In regards to composition, these sub-factors include knowing the specific lens used, the film or digital sensor format, the positioning of the camera, the shifts and swings if a view camera or a tilt-shift lens is used, the exposure settings and the type of film or digital sensor used because these define which dynamic range was recorded. These have to be known to create a specific image design.

In regards to processing, sub-factors include knowing how the film was developed in the darkroom, or how the image was converted in the computer. Here countless variables come into play. In the chemical darkroom, these variables include how long the film was developed for and in what kind of developer? Which paper was the image printed on? Whether dodging and burning were done and if yes in which areas of the image and for how long? What kind of enlarger was used? Was it a cold head or a condenser? How long was the print developed for, in which developer and at what temperature was the developing bath? Was selenium or another toner used? How was the print dried? Knowing what the final print of a photograph looks like is not enough to uncover the ‘secrets’ that led to the creation of its look.

In the digital darkroom, these variables include which type of software was used? What type of processing was applied? What amount of manipulation was done to the photograph? What substrate was the image printed on? Because digital processing allows me to apply many more changes to the image than film processing, these sub-variables have to include both the amount of manipulation applied to the photograph and the nature of these manipulations. Is the goal to make a realistic photograph or is it to create a total departure from reality?

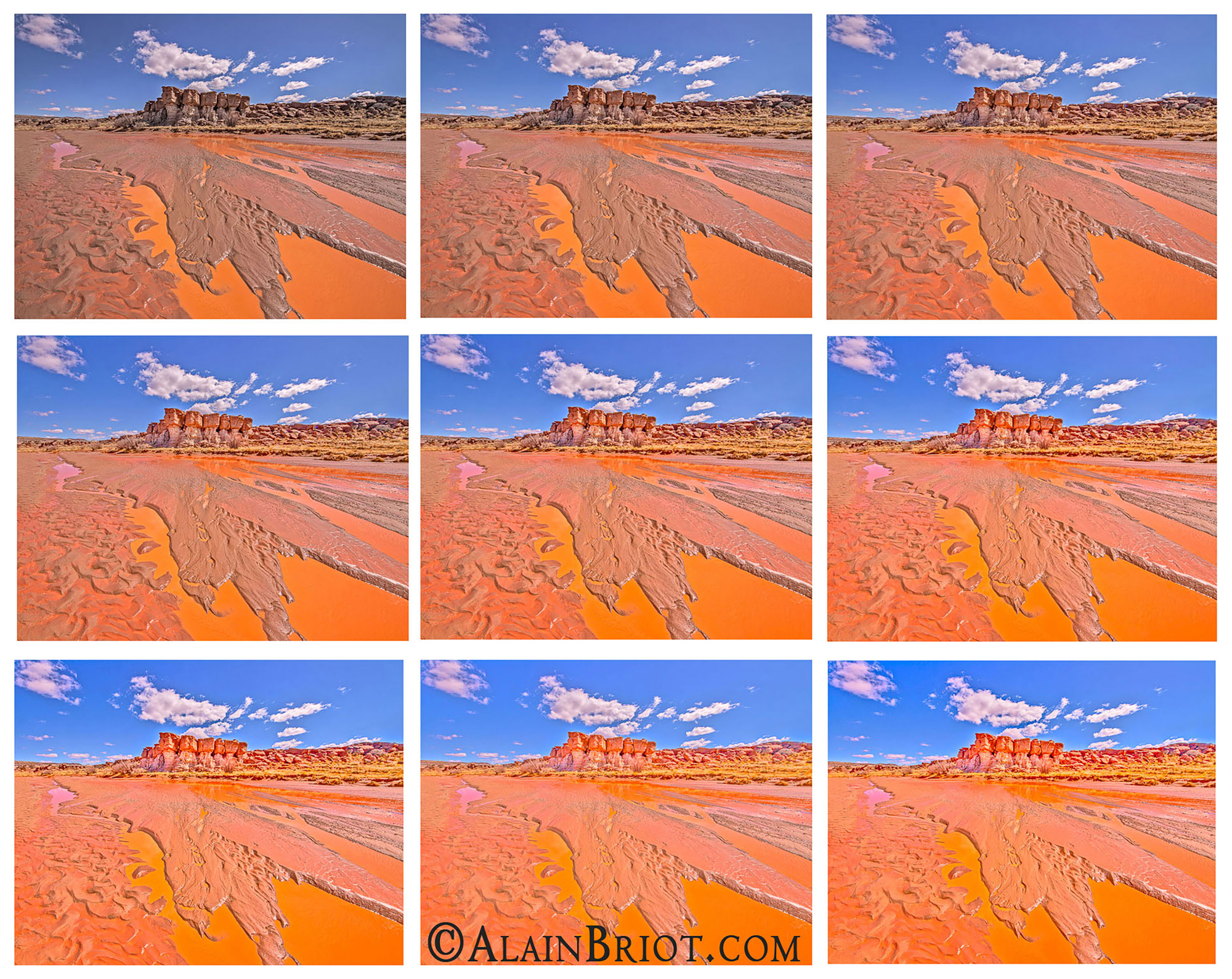

An important side note is that changing the design does not necessarily imply changing all three variables of a photograph. One can certainly do so, but it is unnecessary. A new design can be created by changing two, or only one of the three variables. The image featured in this essay, Wash Collage, is a demonstration of this design principle.

The many variables involved in designing a photograph mean that the same subject photographed by different photographers can potentially result in multiple interpretations and therefore in multiple designs. Depending on the time they visit a specific location and the choices they make the resulting images could be vastly different from one another. The lighting could be different. The compositions could be different. The processing could be different. The final prints could be different. The subject may be the same but because the artists are different their creations have the potential of being different because the three elements of photographic design –location, composition and processing– can be adapted to fit their individual taste, vision and ideas.

I use the words ‘potentially’ and ‘could be’ because doing so is not always the case. Despite the fact that the design variables can be interpreted in virtually endless ways, specific locations are often depicted in the same manner by multiple photographers. This puzzling effect has logical explanations which I will look at in the next essay.

All nine images feature the same location and composition. The only difference is the processing. Yet, the outcome is 8 different designs because changing one variable is enough to change the design.

What’s Next

This is the first essay in a series about applying the craft-based philosophy of David Pye to fine art photography. For the purpose of clarity, I am proceeding step by step in my dissertation of the subjects of design, craftsmanship, and art. To sketch the road ahead here are the tentative titles of the essays in this series, in chronological order:

1 – Art and design

2 – The designs of previous artists

3 – Art of risk and certainty

4 – Art is risk

5 – Diversity and variety

6 – Invention

In the next essay, I will reflect on how Pye’s concept of design applies to the work of past and current artists. I am particularly interested in looking at why we are influenced by the designs of past artists and what are the consequences of this influence.

About Alain Briot

I create fine art photographs, teach workshops with my wife Natalie, and offer Mastery Tutorials on composition, image conversion, optimization, printing, business, and marketing. I am the author of Mastering Landscape Photography, Mastering Photographic Composition, Creativity and Personal Style, Marketing Fine Art Photography, and How Photographs are Sold. My books are available in eBook format on my website. Free samplers are available so you can see the contents of these books for yourself.

You can find more information about my workshops, photographs, writings, and tutorials as well as subscribe to my Free Monthly Newsletter on my website. You will receive 40 free eBooks when you subscribe.

Studying fine art photography with Alain and Natalie Briot

If you enjoyed this essay, you will enjoy attending a workshop with us. I lead workshops with my wife Natalie to the most photogenic locations in the US Southwest. Our workshops focus on the artistic aspects of photography. While we do teach technique, we do so for the purpose of creating artistic photographs. Our goal is to help you create photographs that you will be proud of and that will be unique to you. The locations we photograph include Navajoland, Antelope Canyon, Monument Valley, Zion, the Grand Canyon, and many others. Our workshops listing is available at this link.

Alain Briot

January 2022

Glendale, Arizona

Author of Mastering Landscape Photography,Mastering Composition, Creativity and Personal Style, Marketing Fine Art Photography, and How Photographs are Sold. http://www.beautiful-landscape.com [email protected]