The Language of Art – Part 9 – Levels Of Abstraction In Photography

Introduction

My previous essay focused on defining the concept of abstraction in art and photography. At the end of that essay, I mentioned that abstraction is not a unified concept. I explained that there are different levels of abstraction depending on how far an artist decides to move away from reality. Abstract art can be relatively close to reality, making it possible for the viewer to find out what the subject is by comparing it to reality, or it can be so far from reality that it is impossible to know what the subject is because comparing art and reality is impossible.

Levels of Abstraction in Photography

In photography, most photographers have shied away from abstraction. The majority have remained close to reality, making it possible, and in most instances easy, to find out what the original subject of their work is. However, a few did move away from reality, creating work that distances itself from reality in various amounts, from small to large.

In his book Secret Knowledge, David Hackney provides a timeline showing the distance between reality and artistic representations from 1400 to 2000. A study of this timeline shows that the period during which the distance between reality and artistic representation was the shortest is in the early 19th century, roughly between 1800 and 1870. This coincides with the time when lens-based representations made their appearance.

By lens-based representations, Hackney refers to not only photographs but also other forms of representations that use optical projections. These include the camera lucida, an optical apparatus that uses a series of mirrors and lenses to project reality onto a sheet of paper, making it possible for the artist to draw by following the contours of the projected image. It also includes a second optical device called the chambre claire, a dark room in which a lens placed on one side projects an inverted image onto the wall on the other side, again making it possible for the artist to ‘draw’ by following the contours of the projected image which, once turned right side up, is closer to reality than any previous artistic representation.

These devices made it possible to create artistic representations that were closer to reality than ever before. In fact, these representations were so close to reality as to be photographic, making it possible to identify the exact location shown in the image by comparing it to reality. This can still be done today if the buildings, the streets, or the subjects still exist.

Hackney compares lens-based representations to eyeballing traditional representations. Eyeballing traditional representations refer to drawings or paintings done handheld by looking at the subject directly, without the use of an optical device. Hackney calls them traditional because, until the apparition of lens-based representation in the 18th century, they were the only kind of representation done by artists. They are, therefore, traditional in the sense that this is how reality was represented for over seventeen centuries.

Eyeballing representations are less realistic than lens-based representations. This is why the apex of realistic representations occurred when lens-based devices were invented and became available to many artists. Prior to that, representations were done by eyeballing and were far less realistic, if not definitely abstract.

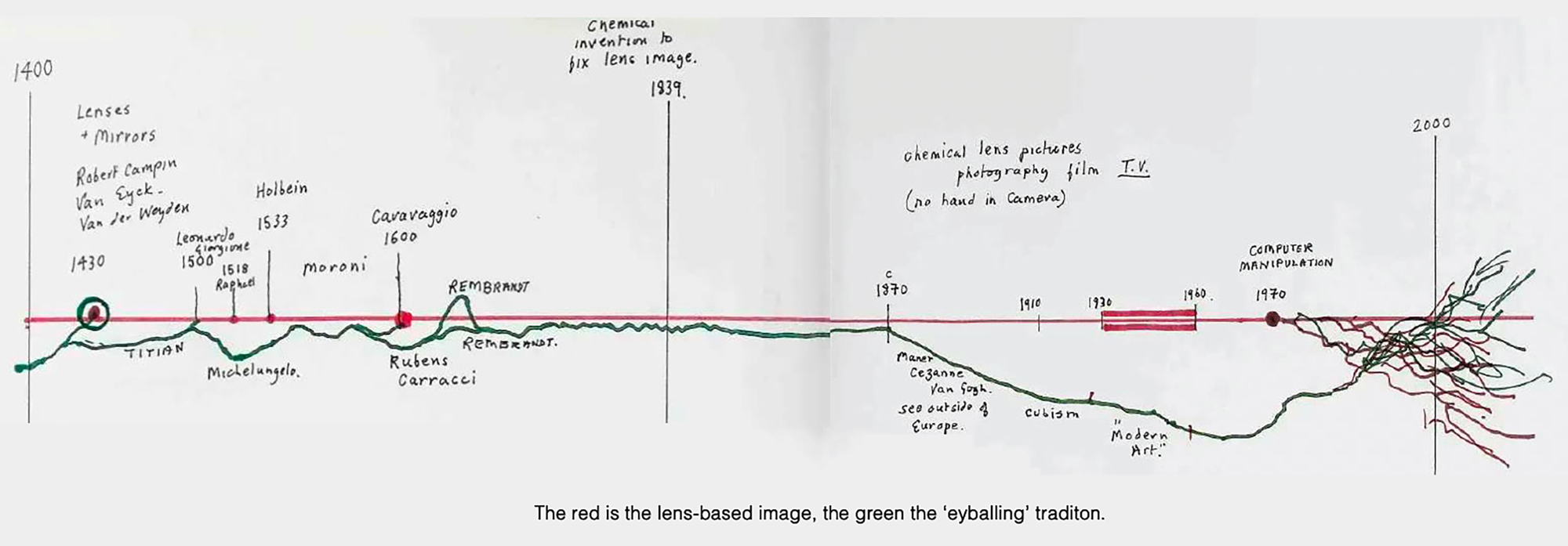

The timeline below is from David Hockney’s book. This timeline shows a red line and a green line. The red line is the lens-based image. The green line is the eyeballing tradition.

The emergence of photography pushed lens-based representations one step further by making it possible to create representations that were virtually indistinguishable from reality. The only difference between an unmanipulated photograph and reality being that the photograph is flat, two-dimensional, smaller or larger than the real subject, and, whether black and white or color, exhibits colors and contrasts that are different, to a greater or smaller extent, than reality.

Examples

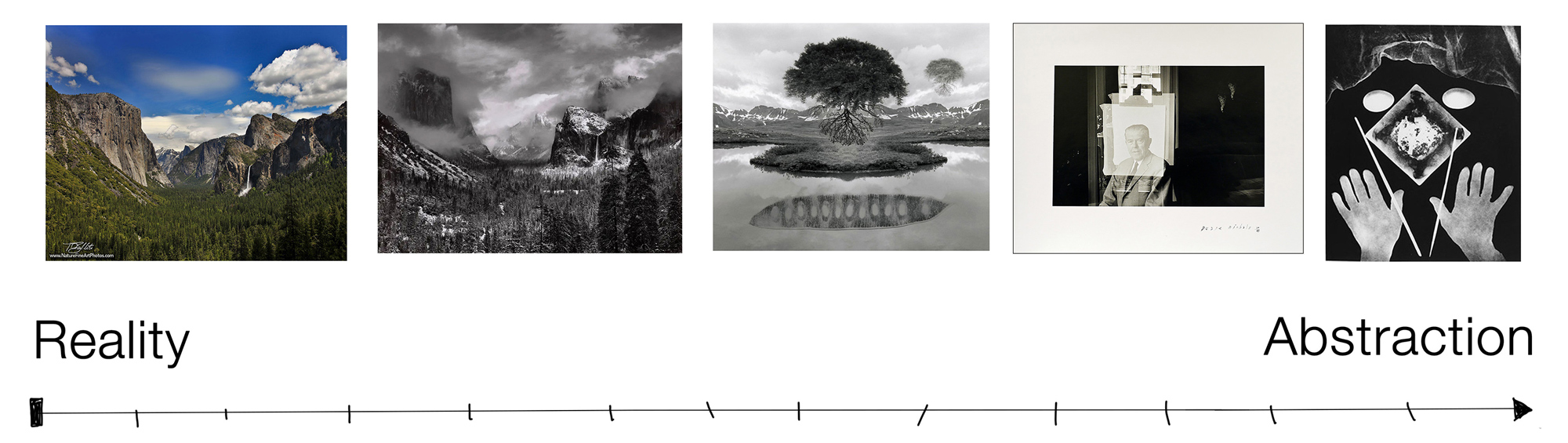

The image below shows five photographs, each demonstrating a progressive departure from reality, going from left to right.

The first is a color photograph of Yosemite exhibiting no manipulation. This image is as realistic as it can be. I would call it a documentary image. It is pretty, pleasant to look at, but shows no distancing from reality besides the changes brought by the photographic medium which I outlined previously. This photograph can be considered, for our purposes, to be a ‘normal’ photograph of Yosemite Valley, similar to the photograph that most people would take when they visit this location.

The second is a photograph of Yosemite Valley by Ansel Adams. Titled Clearing Winter Storm, it was taken from the same viewpoint as the first photograph. However, despite being taken from the same spot, this image demonstrates a higher level of distancing from reality than the first image. First, it is in black and white while we see the world in color. Second, it was taken at a particularly dramatic time of day and year, showing a snowstorm in the process of moving out, with fresh snow, transient clouds, and active weather. Because most people visit this location on clear days, this view is surprising. Third, it exhibits a high level of artistic manipulation in the darkroom through selective dodging and burning of the negative under the enlarger as well as the use of advanced darkroom processing for film and print developing and for toning. These techniques are not available to most people. The abstraction in this photograph stems from the comparison between the ‘normal’ representation of Yosemite, as shown in the first photograph, and the artistic representation created by Ansel Adams.

The third is a photograph by Jerry Uelsmann. It shows elements that are easily recognizable and found in many landscape photographs. A tree, a pond, a mountain range, clouds, and a grassy knoll. These are as realistic as they come. What makes the image abstract is how these elements are organized. The tree is floating above the grassy knoll. The roots of the tree are visible instead of being underground. A shadow image of the tree is floating in the sky. The reflection of the tree in the pond looks nothing like the tree. These elements may be realistic but their organization is illogical and unlike anything that exists in reality. On top of that, some of these elements are purely impossible. Trees do not have shadow images floating next to them. The reflection of a tree cannot be the image of something which is not a tree. Roots do not grow out of the soil. Trying to understand this image from a rational perspective is frustrating, if not outright impossible. The only way to make sense of it is by approaching it as a surreal image, as the representation of a dream state. Surreal images are abstract. One of the techniques used by many surrealist artists is to combine realistic and unrealistic elements. Salvador Dali made extensive use of this technique. Uelsmann does the same in his photography.

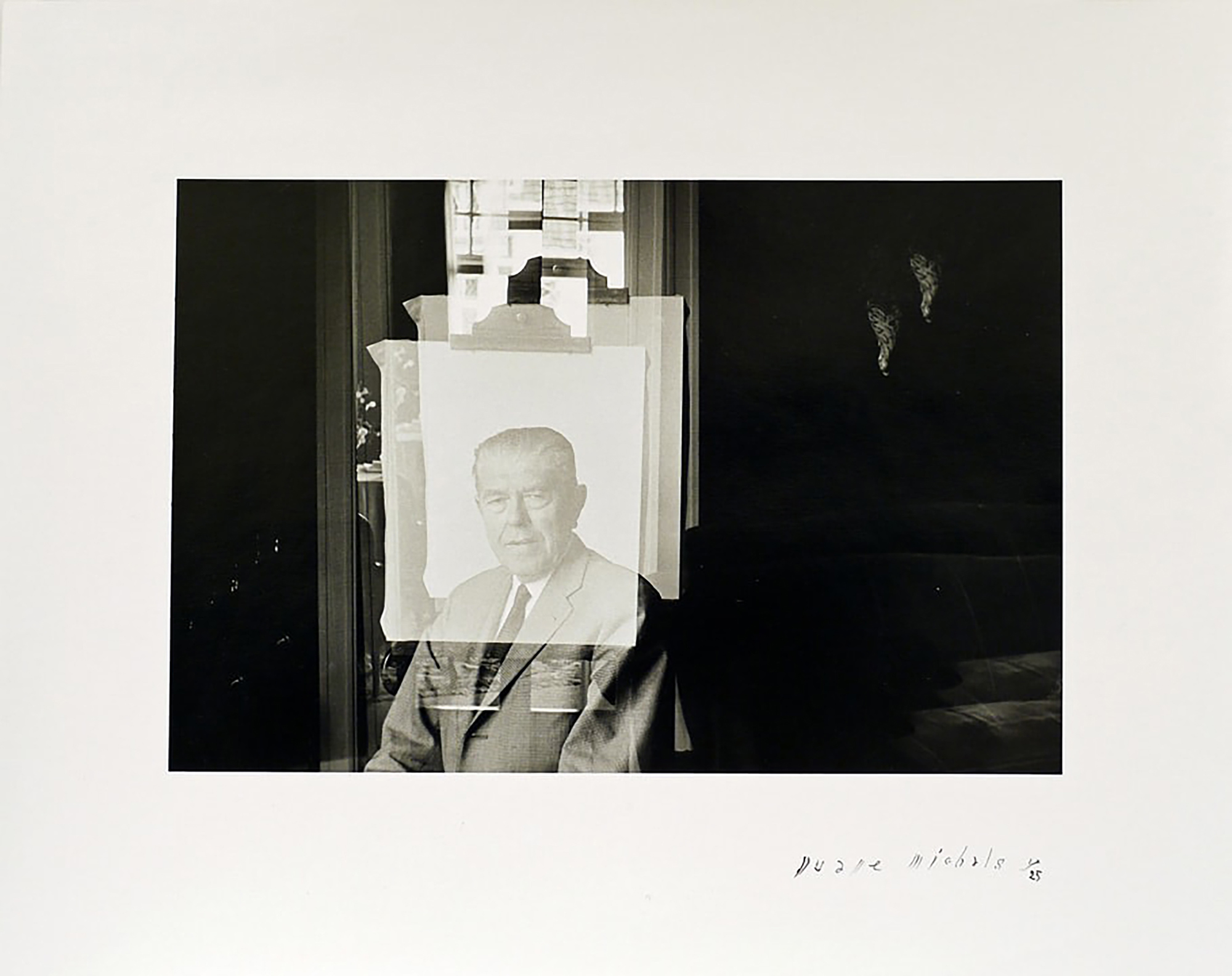

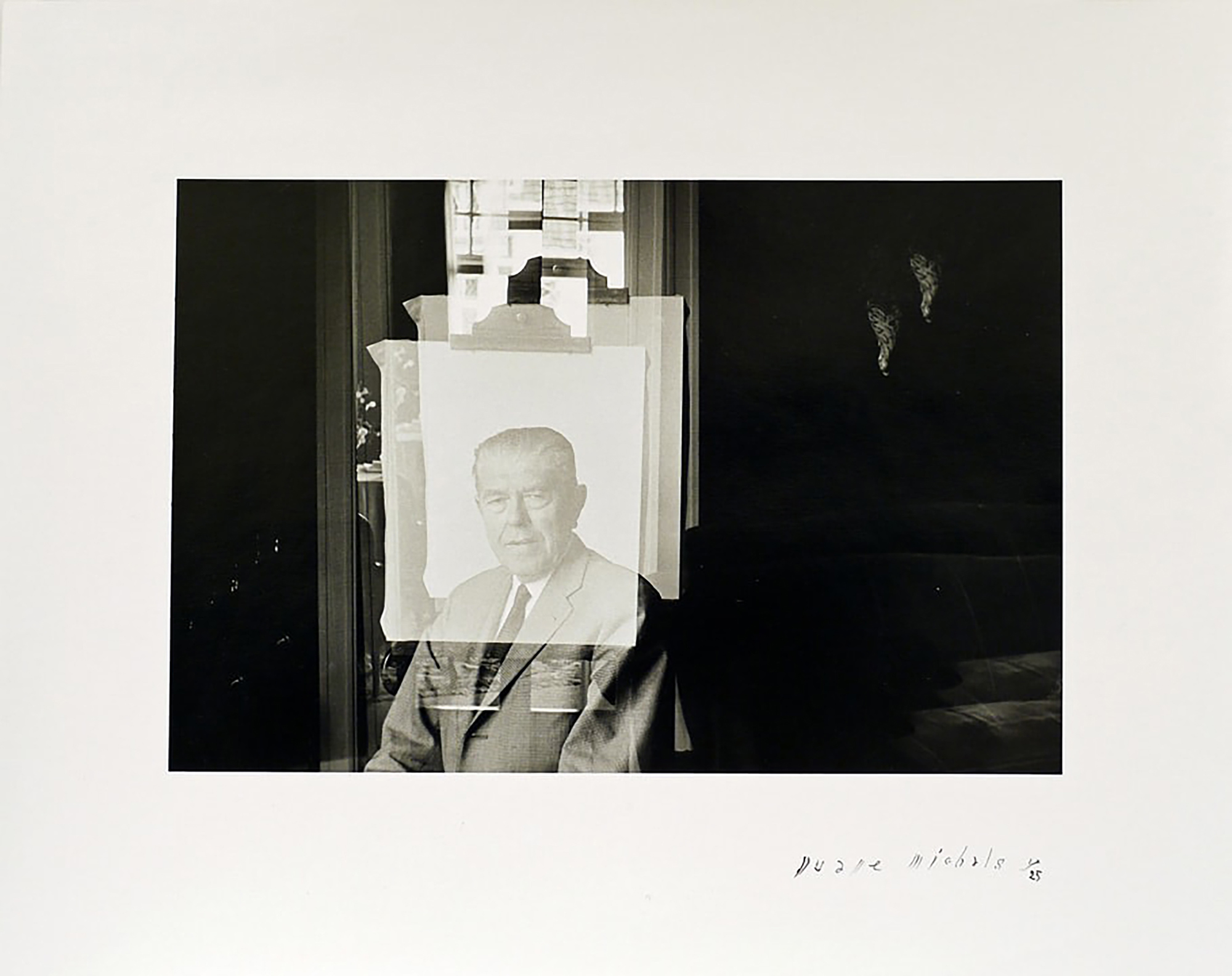

The fourth is a photograph by Duane Michals. It shows an older man seated in front of an easel with a sheet of paper clipped on it, as if it was ready for the artist to draw or paint. The background shows elements found in a bedroom or a living room. Door jambs, window, a bed maybe. Again, as in Uelsmann’s photograph, nothing is strange in this itemization of the image elements. However, when looking at how these elements are arranged, strangeness is all over the place. The old man’s face is covered with a semi-transparent sheet of paper attached to a clipboard. See-through rectangular images are superimposed on his torso. The background of the room is dark, and the elements in that space are hard to distinguish. The overall effect is surreal. I feel I am looking not at a person but at an apparition of a person who is either dead, missing, ethereal, or somehow not physically present. It is about who that person was rather than about what that person looks like in a

portrait. It is definitely an abstract image, but one that does not use unreal elements the way Uelsmann’s photograph does. Instead, Michals uses realistic elements but creates an abstract effect by layering these elements in a semi-transparent manner and by using light and shadow to create not only mystery but also a space where the imagination of the viewer can roam and bring meaning to an otherwise inexplicable image.

The fifth is a photograph by Man Ray. Called a Rayograph, this photograph was created without the use of a camera. Instead, Man Ray positioned a variety of objects onto a sheet of light-sensitive photo paper, turned on the enlarger to expose the paper to light, and developed the print. The outcome is an image on which the areas covered by the objects, and therefore protected from the light of the enlarger, remain white, while the surrounding areas are black, having been exposed to the light of the enlarger. Man Ray’s photograph is interesting because no camera was used. In fact, at the time it was created, some people complained that it was not a photograph because photographs must be done with a camera. The fact is that the word photography means writing with light, from the Greek Photos, light, and Graphos, writing or drawing. There is no reference to a camera in the word photography. Man Ray’s images are, therefore, photographs just as much as those of Ansel Adams, Uelsmann, Michals, or any other photographer.

What makes Rayographs truly interesting is their relationship with reality. The objects in these images are, for the most part, easily recognizable. However, Rayographs are abstract because these objects are not presented in a logical or realistic manner. In the Rayograph featured here, the hands, the sticks, the square, and the circle are all identifiable as such. Yet, the combination of these elements is mysterious. No explanation, rational or other, is offered for their presence in the image. The viewer is free to decide what the image means and why these objects are shown together. It is up to the audience to decide whether this is an aesthetic arrangement of objects or if there is a deeper meaning to the image.

The abstraction in Man Ray’s Rayographs does not come from being unable to recognize the objects in his photographs. It comes from being unable to give an answer as to why these objects are featured in the image. We recognize these objects and these shapes. We know there is a square, two circles, two sticks, and two hands. However, we don’t know why they are shown together. We don’t know for what purpose. We don’t know what this means. Is there an unspoken message? If so, what is it? If we come up with an answer, how do we know this answer is correct? How do we know if it is the only possible answer? Clearly, many other answers are possible. Therefore, our answer, whatever it may be, is bound to be different than that of other viewers.

The impossibility of coming up with a single, definite answer is what creates the abstraction. Man Ray’s Rayographs are abstract because they do not mean something specific. They are also abstract because they do not refer to a specific reality. Each object and element looks real, yet together, these elements do not represent a scene that exists in reality. When we see a photo of Yosemite, even if it is in black and white and was artistically manipulated to exhibit fine gradations of greys, we know it is Yosemite. There is no question in our minds. Even if we have never seen or heard of Yosemite, we know it is a photograph of a landscape, of a valley filled with trees and lined by cliffs located somewhere on planet Earth. Not so with Rayographs. We don’t know where the objects in the image are located. We don’t know why these objects are arranged the way they are. We are left with a representation of objects and elements whose purpose eludes us.

Conclusion

The five examples I discussed are all photographs. However, these photographs have radically different purposes and goals. Most importantly, in the context of this essay, all five exhibit a different level of abstraction from reality. The first is so close to reality that the only differences are those created by the photographic medium. The last is so far from reality that the meaning and the purpose of this photograph are not only obscure but open to conjecture. The three others hoover between reality and abstraction, offering both a glimpse of reality and a push towards abstraction.

Creating reality is simple. Just take a photograph and do nothing to it. The only differences between that image and reality will be those induced by the photographic medium. It won’t be real, because it will be flat, two-dimensional, smaller or larger than the original, and with colors and contrasts different from those in the real world. However, it won’t be abstract either because the camera was used as a recording device. One can say the process of capturing the scene or the subject was left to the camera and that the photographer had no intent besides documenting what was in front of the lens.

Creating abstraction is more complicated, regardless of the level of abstraction the artist wants to reach because it demands work beyond the taking of the photograph. This work can take many forms, but it has to be done intentionally. In this essay, I showed the abstract work of five photographers. Many more types of abstraction work have been done by other photographers. For example, for some photographers, the abstraction takes place in the camera at the time of capture by recording events that are so uncommon as never to happen again, events that are never to be seen by another person. Such is the work of Henri Cartier Bresson, for example. Cartier Bresson created a large amount of his work in Paris. Many viewers assume that Bresson’s images are realistic photographs of Paris. These people are shocked when I explain that, despite being from Paris and having lived there 26 years, I have never witnessed any of the scenes captured by Bresson.

People suppose that the scenes photographed by Bresson occur regularly in Paris because they were recorded with a camera and are made available as prints that were not manipulated in regards to their content. The reality is that these scenes do not happen regularly. In fact, in my experience, they only occurred in front of Cartier Bresson. Most of them took place so fast that the only reason Bresson captured them was that he was looking for what he called the moment decision (the decisive instant) and because the camera can record events that last only a fraction of a second. Did I see such scenes? Not that I can remember. Why? Because I was not looking for them. And If I had, who knows if I could have recorded them. All it would take to go from reality to abstraction is pressing the shutter a fraction of a second too early or too late.

And yes, Bresson’s work is abstract. Even though he recorded scenes of everyday life, the way he recorded them is unlike the way most people see them. I know for one I did not see any of them. I also know that there is more to creating abstract scenes that meet the eye. In this essay, I described some of the techniques used by abstract photographers. However, there are many more, some known to all, and some known only to the artists who created them. As proof is a book featuring several of Cartier Bresson’s interviews and, published in 2023. This book is titled Puis-je garder quelques secrets? which translates as Can I keep a few secrets to myself?

The Next Essay

This essay focuses on levels of abstraction in photography. In this essay, I covered the work of 5 photographers in the context of the level of abstraction in their work. Because I am a photographer myself, I wanted to include a discussion of the level of abstraction in my personal work. However, I try to keep each essay to a reasonable length, and discussing my will make this essay unnecessarily long. So, I will talk about my work on the language of art in the next essay, number 10, in this series. In fact, there will be 2 more essays on abstraction because after discussing abstraction in my work, I will discuss abstraction in art in what will be essay number 11.

About Alain Briot

I create fine art photographs, teach workshops with Natalie, and offer Mastery Tutorials on composition, image conversion, optimization, printing, business, and marketing. I am the author of Mastering Landscape Photography, Mastering Photographic Composition, Creativity and Personal Style, Marketing Fine Art Photography, and How Photographs are Sold. All 4 books are available in eBook format on our website at this LINK. Free samplers are available.

You can find more information about our workshops, photographs, writings, and tutorials, as well as subscribe to our Free Monthly Newsletter ON OUR WEBSITE.. You will receive 40 free eBooks when you subscribe.

Studying Fine Art Photography With Alain and Natalie Briot

If you enjoyed this essay, you will enjoy attending a workshop with us. I lead workshops with my wife Natalie to the most photogenic locations in the US Southwest. Our workshops focus on the artistic aspects of photography. While we do teach technique, we do so for the purpose of creating artistic photographs. Our goal is to help you create photographs that you will be proud of, and that will be unique to you. The locations we photograph include Navajoland, Antelope Canyon, Monument Valley, Zion, the Grand Canyon, and many others. Our workshop listing is available at this LINK.

Alain Briot

January 2024

Glendale, Arizona

Author of Mastering Landscape Photography,Mastering Composition, Creativity and Personal Style, Marketing Fine Art Photography, and How Photographs are Sold. http://www.beautiful-landscape.com [email protected]