The Language of Art Part 5 – Mythology

Introduction

In the first essay in this series, I presented several situations in which a lack of knowledge of the artist’s referent led to an erroneous understanding of the work. In this fifth essay, I want to mention additional examples of misunderstandings. Because this aspect of the language of art is affected by the referent, I decided to publish it after my essay on the referent.

The Referent and The Archaeological Record

In my first essay, I talked about how I decided to disregard the original intent, the referent as I call it, of Inca funeral weavings. I took this decision not because I did not know the original meaning of these works of art but because I did not feel that the original referent applied to me. The reasons behind my decision were multiple: I am not an Inca, the art period during which these weavings were produced is no longer in existence, and for me, these weavings have a decorative value that transcends their original purpose.

However, there is another element at work here: the culture that created these works of art not only no longer exists but is lost to the sands of time. Little is known about it. There is no written record of their religious beliefs. There are no texts explaining precisely how and why these weavings were used. In short, the archaeological record is lacking. While some cultural aspects are known, much is left to supposition and personal opinion. Even the opinions expressed by archaeological experts are tentative rather than objective.

It could be said that this applies to ethnic artwork. However, such is not the case because a large amount of ethnic artwork is produced by cultures that are still in existence, even if these cultures have been affected by the infringement of today’s technologically advanced cultures. Such is the case of African masks, for example, and more precisely, Congo Masks. Congo Masks are largely unintelligible to an audience not fluent in African Art. However, these masks continue to be produced and used in ceremonies today. Therefore, a lot of ethnic information about their production and their role in the society in which they are used is known and accurate. This information is fact, not opinion.

However, even though accurate ethnographic information is available, Congo masks often come across to Westerners as scary or obscene. For example, they often show bare genitalia, which is not favored in traditional Western imagery. This type of representation is not widely accepted in our culture. However, in Congo, they are considered normal depictions of the human body.

We are talking about mythology here as it applies to different cultures. These representations are mythological, not symbolic. They represent mythical beings, not real people. Here again, lack of knowledge of the artist’s intent, of the referent, leads to both a discriminative and an erroneous interpretation of the art.

Mythology

Ekkehart Malotki is a linguist who studied and recorded Hopi mythology stories. Many Hopi stories are frightening because they address the passage from the living to the afterlife, often with dire consequences. In Hopi mythology, the transition from life to after-life is not easy. It is filled with challenges that affect how the departed’s soul will fare in the after-world. I expressed this concern to Ekkehart in a private conversation, explaining that I found Hopi stories to be scary. His response was enlightening. He simply said, ‘Well, of course they are scary if you believe them!’

Implied in his response is the fact that mythological stories depend on belief to be effective. They are scary if we believe them, and they are not scary if we do not believe them. How we understand the meaning of these stories, of this language, depends on our personal perspective, our cultural baggage, and most importantly, the referent we bring to them. The implications of these stories are real if we believe them and non-existent if we do not believe them.

Joseph Campbell points to this aspect of ethnographic interpretation in his writings about myth. For Campbell, myth understanding requires cultural understanding. In other words, understanding the culture that created the myth is necessary to understand a specific myth.

Campbell’s writings focus essentially on oral or written stories. However, the dependence on cultural knowledge extends to mythical visual arts, works of art that physically depict mythical beings. For example, and to return to my previous example, Hopi dances feature beautiful costumes, complex timing based on the seasons, and elaborate choreography. However, their actual meaning is inaccessible to the non-initiated because the dances themselves do not give away this meaning.

To take another example, the same is true of Navajo Yei Bei Chei rituals. In Navajo culture, the Yei Bei Chei are both tricksters and messengers whose role is to carry the messages of the gods to humans. In one specific ritual, the Yei Bei Chei go around town stealing objects from humans and demanding a ransom for their return. They are bare-chested, dressed only with loincloths, and their bodies are painted white. In an instance that I personally witnessed, the Yei Bei Chei stole the plastic tube container used to transfer cash from the customer to the teller at the Chinle Wells Fargo Bank drive-thru. According to the ritual, their goal was to give the plastic tube back in exchange for a donation of money or gifts.

This act is perfectly understood by Navajos because it takes place each year. Chinle residents are familiar with it, understand its true meaning, and act accordingly. They are culturally fluent, know their ‘alphabet, and are mythologically literate. They have gained this literacy because they grew up surrounded by Navajo mythology.

However, the same act is incomprehensible and often misinterpreted by non-Navajos because we do not share the cultural literacy necessary to understand the Yei Bei Chei actions correctly. To non-Natives, Belagana as white people are called in Navajo culture, the Yei Bei Chei stealing the money carrier tube at the Chinle bank is understood literally as a theft of bank property and of customers’ money. This is because to non-native onlookers, the true ethnographic meaning of the Yei Bei Chei ritual is unknown. We do not understand that the goal of the Yei Bei Chei is to get donations for the items they ‘stole’ temporarily and will return upon being given something of value to them, be it food, money, or other.

Not All Art Can Be Explained

These examples of potential ethnographical and mythological incomprehension provide an opportunity to make a bridge with the interpretation of Modern Art. Let’s take as an example the work of Picasso or Dali, two artists working in a modern art movement. Who knows precisely what Picasso really meant when he painted the images of women in the style he is known for? We do know that he represented several angles of view in the same painting and that he was more interested in the facture of the painting than in the depiction of a realistic portrait. Similarly, we know that Dali expressed a dream-like state in his paintings. His referent was Surrealism, and each piece, no matter how ‘off the wall’ it might appear, featured at least one element painted in a realistic manner. This element, be it an object, animal, person, building, or other, could be identified as real.

Yet, despite this knowledge, who can tell exactly what went on in Dali’s mind, or in Picasso’s mind, or in any other Modernist artist’s mind for that matter, when they created their work? After all, the meaning they wanted to express and share with their audience was shared visually. Just like the Inca and other pre-historic artwork, no written record exists. No text was written by these artists explaining precisely what they meant to say in their paintings. Why not? Because they are visual artists, not writers. They express their vision in images, not in essays or novels. The meaning of their work is contained in their paintings, and it is up to us to ‘fill in the blanks’ left by their lack of textual or factual information.

Mythology, Modern Art, and Referent

Art can never be totally explained, whatever its inspiration might be. Whether it is mythological, cultural, or personal to the artist, the referent can never be fully known. The absence of a fully-revealed referent is what gives art its mystery. It is also what allows artists to give an ambiguous dimension to their work.

This ambiguity also allows the audience to reach diverse interpretations of the work.

The language of art is not meant to be fully descriptive. It is not meant to reveal everything. Its purpose is not to shed light upon every aspect of the work. Instead, the language of art allows the creation of a message with multiple meanings. A message that is ambiguous, open to interpretation and subject to personal interpretation.

I will present additional examples of ambiguous art in my next essay, number 6 in this series, which focuses on Modern Art. Because this movement emphasized abstraction, it is an excellent subject of study in regard to the challenges of understanding the art language.

About Alain Briot

I create fine art photographs, teach workshops with Natalie, and offer Mastery Tutorials on composition, image conversion, optimization, printing, business, and marketing. I am the author of Mastering Landscape Photography, Mastering Photographic Composition, Creativity and Personal Style, Marketing Fine Art Photography and How Photographs are Sold. All 4 books are available in eBook format on our website. Free samplers are available.

You can find more information about our workshops, photographs, writings and tutorials as well as subscribe to our Free Monthly Newsletter on our website at http://www.beautiful-landscape.com. You will receive 40 free eBooks when you subscribe.

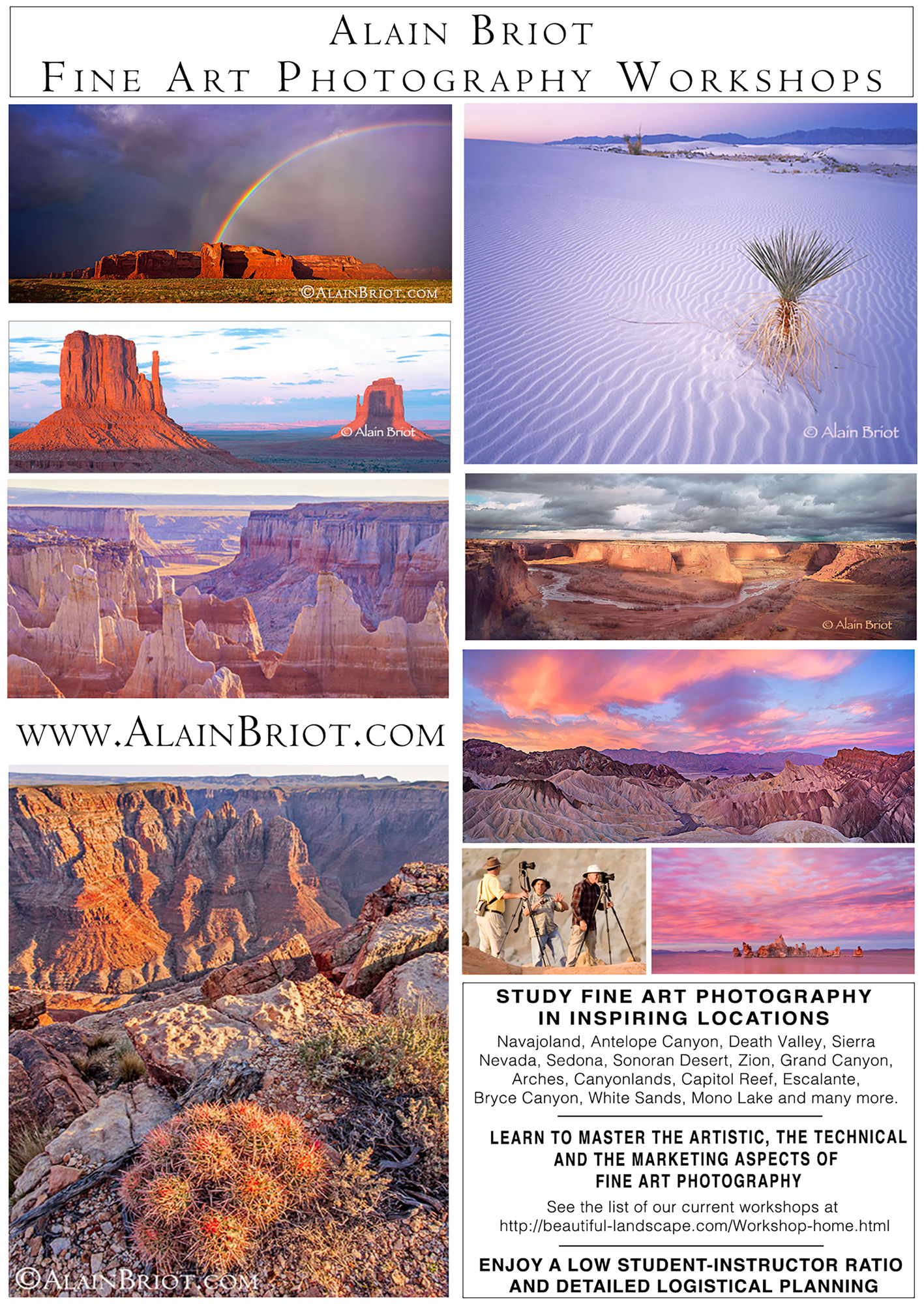

Studying Fine Art Photography With Alain and Natalie Briot

If you enjoyed this essay, you will enjoy attending a workshop with us. I lead workshops with my wife Natalie to the most photogenic locations in the US Southwest. Our workshops focus on the artistic aspects of photography. While we do teach technique, we do so to create artistic photographs. Our goal is to help you create photographs that you will be proud of, and that will be unique to you. The locations we photograph include Navajoland, Antelope Canyon, Monument Valley, Zion, the Grand Canyon, and many others. Our workshop listing is available HERE.

Alain Briot

September 2023

Glendale, Arizona

Author of Mastering Landscape Photography,Mastering Composition, Creativity and Personal Style, Marketing Fine Art Photography, and How Photographs are Sold. http://www.beautiful-landscape.com [email protected]