Inspired By David Pye Part 2

The Designs Of Previous Artists

It needs to be said and heard – it’s OK to be who you are.

Hailee Steinfeld

Introduction

In my previous essay, I looked at David Pye’s concept of design as it applies to the world of fine art. In this first essay, I focused on how the role that design plays in the creative process. In this second essay, I continue my study by looking at why we either create new designs or re-create the designs of previous artists.

The Designs Of Previous Artists

I concluded the first essay by explaining that landscape photography design is defined by three main factors: location, composition, and processing. As such these three elements define an artist’s style.

There are two ways to create a design and, by extension, to create a style. We can create a new design, or we can copy an existing design. In the first instance, we create something that has never been seen. In the second instance, we copy the design created by another artist.

Creating a brand-new design is challenging. When making something entirely new we must invent every aspect of the design. All we have to go by is our vision and imagination because we are trying to make visible something that so far exists only in our mind. We are trying to create something that does not have a three-dimensional presence yet. Something that only we can see.

Making a copy of a pre-existing design is much easier. When making a copy, we only need to follow a model, a blueprint. We are re-making something that is already visible to all, something tangible that can be touched, felt, and experienced with all our senses, something that exists in three dimensions. All we need to re-create the photographs of those who came before us, of the artists we respect and admire, is to find the locations where their images were created, re-create their compositions, and process the photographs in a similar way so that our final prints are comparable to their final prints.

However, design, as we saw in the previous essay, is an abstract concept, a Platonic construction. It is the shadow of objects passing in front of the entrance to the cave, not the objects themselves. So, when trying to re-create a pre-existing design, we can never duplicate that design exactly because we do not know what the vision of the original artist -the ‘object’ in the cave allegory- was. Duplicating the photographs of those who came before us is, therefore, an impossible goal. It is tempting to believe that this impossibility is caused by changes in the three design variables. Certainly, locations have changed and are different today. Certainly, gear has changed and is different today. Certainly, processing has changed and is different today. And certainly, put together, changes in these three variables mean creating exact duplicates is a near-impossible task. I agree to all that.

However, the most challenging aspect, and the reason why making a copy of an existing photographic design is virtually impossible, is because we are not the original artist. We are not those who came before us. We do not think like them, see like them, or feel things like them. We do not see what they saw and we do not feel what they felt. We do not have their vision. We cannot experience the emotions they experienced. This is a fundamental problem because to re-create a work of art one must not only recreate the physical situation in which the artist was, one must also recreate the emotional condition the artist experienced. This means that one must become that other artist. This is impossible because we can never become someone else. This goal is a Platonic construction, a goal that is impossible to reach. To return to the allegory of the cave, the best we can do is imagine what the objects those who came before us saw looked like, based on the shadows passing in front of the cave. What these objects actually are, what they look like in the light of day, in the three-dimensional world, is forever out of our reach.

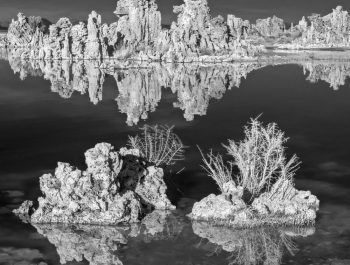

Who knows who took the first photograph or made the first drawing or painting of the Left and Right Mittens? What we do know is that this is one of the most iconic photographic designs in the world.

It is also one of the easiest to duplicate.

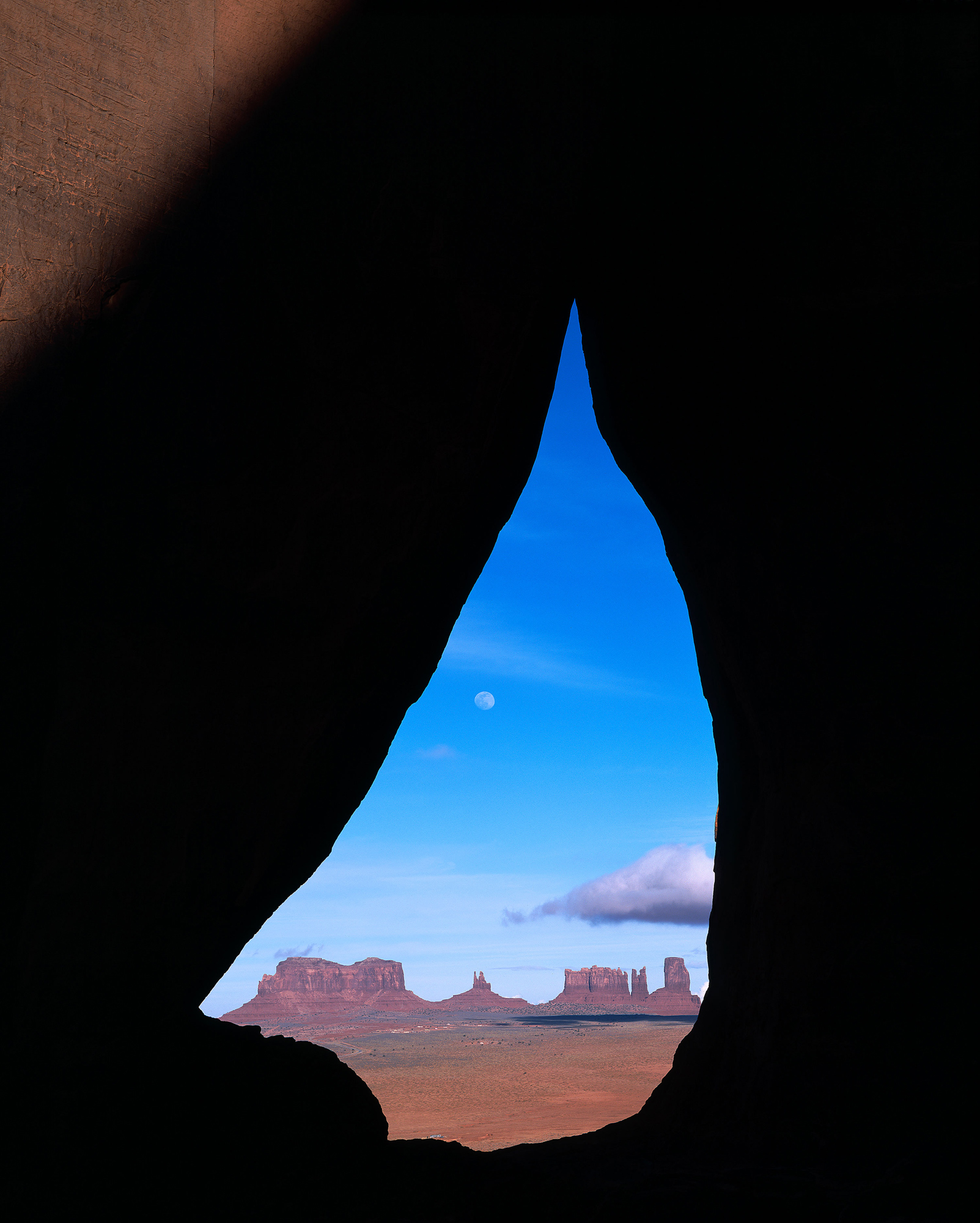

Teardrop Arch

The allegory of the cave phenomenon, the shadows interpreted as reality, was never made clearer to me than the day I photographed Tear Drop Arch in Monument Valley for the first time. In all honesty, at the time, this allegory was not present in my mind. I knew about it because having studied rhetoric and philosophy, I had read Plato and was familiar with platonic concepts. However, back then my goal was simply to recreate a photograph that had made a strong impression on me and nothing else.

I had seen that photograph in a book by David Muench. I had the image in mind, but I did not have the book with me. It was a perfect ‘shadow as reality’ situation. I remembered or thought I remembered, that in Muench’s image the clouds in the sky were perfectly spaced, almost with geometric precision, and that the moon was rising in the middle of the image. Also, the rock face in the foreground, the Teardrop Arch, was fully lit. I had timed my visit to be there on the day of the full moon. There were clouds in the sky, but they were not positioned where I wanted them to be. The moon was rising, but not in the ‘right’ place. So, I waited for things to improve, for the elements of the composition to be similar to those in the image I carried in my mind. I had the right location. I had the correct lens, a short telephoto, and I had framed the image in a similar fashion. Now if the clouds, the moon, and the sunlight would just cooperate, I would be golden.

However, as I waited, the clouds refused to cooperate. The moon continued to rise, but in a different location, the wrong one. As time passed, the sun went down and the rock face started to get in the shade. By the time I took the photograph, it was almost completely in darkness, with only a sliver of light still present in the top left corner. I left with a feeling of defeat.

When I returned home, I compared my image to the one in the book. There I saw that the clouds in the Muench image were not where I thought they were. They were spaced randomly. The moon wasn’t in the center either; it was off to the side. My memory of the image I wanted to copy was inaccurate. I realized I tried to create a copy not of an image that existed, but of an image I imagined.

In the end, I was left with a photograph that featured a completely different organization of the elements than I originally intended. The location was the same as in Muench’s image. The composition and the lens I used were the same. But the photograph was not the one I wanted to get. However, it was unique. It was mine. It was not just as good. It was better because it was mine.

This realization was a breakthrough. An aha moment. An epiphany. I had created an image against my will, in spite of myself. I had failed in creating a copy of Muench’s design, but I had succeeded in creating something new and different. I had created an image that I did not know could be done, a photograph I had not seen before, a photograph that was entirely mine.

This is the photograph whose creation I described above.

The Inspiration Of A Lifetime

We all go through the same experience: we look at books, we visit exhibitions; we attend gallery shows; we scour the web, we subscribe to magazines, and more. In doing so we see and experience the work of previous photographers in different ways and we are inspired by it. Over time, given enough books, shows, museum visits, web viewings, and so on, we zoom in to the work of specific photographers who are photographing a specific subject and treating it in a specific style. We are attracted to their work for personal reasons. Often those reasons are difficult to explain because they are emotional rather than rational. We find it challenging to describe them or put them into words because they are non-verbal. We just know that we love their work and that we want to do what they did. We want to photograph the same subjects, go where they went, find the locations they photographed, be there at the same time of day and year, compose our images the way they composed theirs, and finally process and print our images the way they did. We are enamored with the outcome of their work and we long to create work that is as good, as beautiful, and as inspiring as theirs. It is a guttural reaction.

This process is pretty much the same for all artists and by extension for all photographers. We are inspired by the work of other photographers and we start by imitating the style and the work of those who came before us. This is pretty much the approach we all follow when we decide to create our own work. Few, if any, launch into the creation of original work immediately, while they are students learning the ABC of Photography. Certainly, there are exceptions, and I am sure that some examples can be found, but it addresses such a small number of practitioners that it is just as well be ignored because it is not representative of the situation I am discussing here.

At some point, as our learning and practice progress, we face a decision: do we want to create our own designs, our own photographs, or do we want to re-create the work of those that inspired us? Some artists gradually depart from the work of those who inspired them and eventually end up creating their own work. Others continue finding motivation in re-creating the work of those who they consider being their masters.

Of course, it can be said that given enough time, practice, and experience we will inevitably create, one way or another, through thick and thin, success and challenges, our own photographic style. I truly believe that to be true because it is inevitable. No matter how small the changes we make to the work of those who first inspired us, if we make enough changes and if we do so over a long enough period of time, we will ineluctably find that our work becomes increasingly different from their work.

The issue then is not whether we imitate the work of previous photographers or create our own style. The issue is how long does it take for us to create our own style? This is a question whose answer is found in time and dedication. Are we going to be committed to photography long enough to eventually be able to create work that is original, uniquely ours, and no longer a copy of previous photographer’s work?

Attempting to answer this question leads to asking other questions: why does it take so long to move from re-creating the work of previous artists to creating our own work? And, more importantly, perhaps, why does it take some of us longer than others? I believe it has to do with the difficulty of the task, or rather with what is required, to complete this task. I think that what is required is asking difficult questions and finding answers to these questions. These answers, and these questions, relate to our vision of the world. How do we see the world and how do we want to represent the world in our photographs? These questions have to be asked and answered by ourselves. We can talk to others about it, and we can get ideas about possible answers, but eventually, the meaningful answers have to come from us. This is because we are seeking answers about ourselves and about our work, and this is a process that can only be done by us.

For many, the move to creating art is a move away from the science and technology-based society in which we all live to a field dominated by opinion and personal experience. It is a move that calls for expressing our own experience, regardless of outside opinion, without adhering to generally accepted notions. So then why follow the style and the approach of those who came before us? Doing so is counterproductive. It is against the very foundation of art.

This distancing, this decision to not follow the status quo, the accepted norm, the fashionable styles, the rules, and by implication, the work of the successful artists that came before us, takes more time for some than for others. For some, it is almost instantaneous. A short learning time is all they need before they are able to launch into a full-fledged demonstration of their inner vision. For others, it takes much longer. Their childhood, their training, their professional life, their parents and friends, even to some extent their social activities, all combine to create a chasm between what they have been trained to do and have done so far and what art calls for them to do now. The questions take longer to come up and, of course, the answers take that much longer to be found. The process is often arduous and conflicted. Periods of progress and forward motion are followed by long instances of questioning, doubting, and hesitation. Whatever progress was made is put on hold, if not closeted or worse forgotten altogether.

This pattern of forward progress followed by backward retreat is often repeated multiple times. Some, quite a few I would say from experience, stop somewhere along the way, at a particularly difficult moment, usually when the situation becomes untenable. Having to make a decision, they make one in favor of the status quo, of the norm, of what is accepted, washed, and safe. Others press on regardless, unsure whether the future will bring success or failure, but aware that their sanity hinges on not quitting. For most, if not for all, this process is a struggle, and those who stick with it, those who do not give up, are those who eventually develop an unmistakable personal style, a style that we may say is born of the challenges they faced along the way. Those are the artists, the true artists, and their art is all they need to show to prove that the battle, for it is a battle, raged intensely, was worth it because it led to victory in the end.

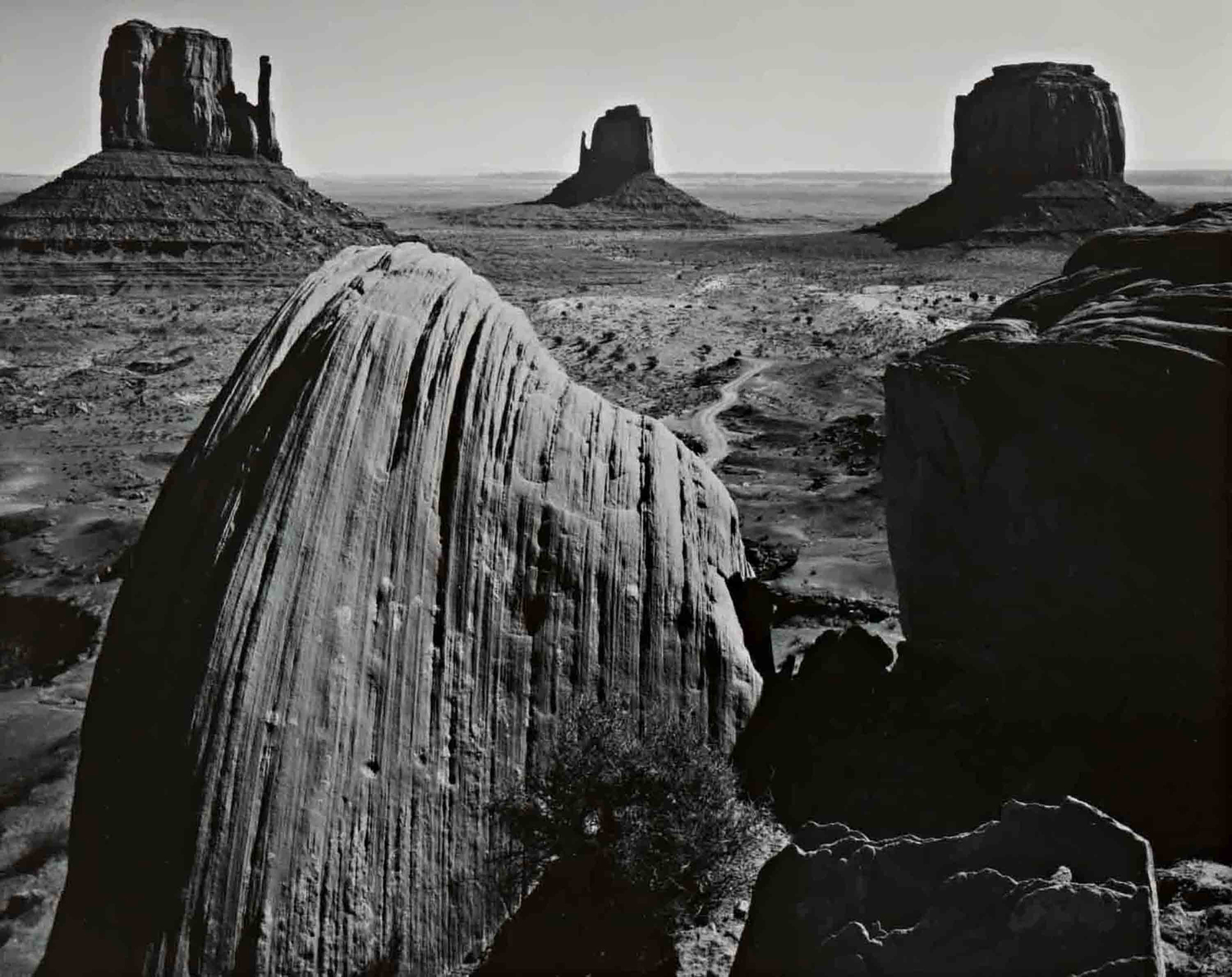

This alternate design, created by Ansel Adams, uses large foreground rocks to complement the left and right mitten. The necessity to precisely line up the foreground and background elements makes photographers look for the proverbial tripod holes. The foreground rocks have become so famous that they are called the “Ansel Adams Rocks’ by photographers.

This is my version of Ansel Adams’ photograph. Here too, just like with Teardrop Arch, my desire to create a copy of a photograph created by an artist who came before I was dwarfed by my partial recollection of the image. The original photograph features all the three monument valley buttes and the rock on the right is cropped. My version features only two of the buttes and the rock on the right side is larger. The original is in color while my version is in color.

Temptation

It is tempting to reproduce preexisting designs because we know they will be successful. They have been successful in the past and they will be successful again in the future. History is our witness and our safety. It provides us with a haven for the anxiety brought by creating something never seen before. By doing so we take no chances. There is no risk except being able to measure up to the original artists, something that, if we fail, we can chalk up to lack of experience and remedy on our next attempt. A trophy shot is exactly that. It is a blueprint we collect and add to our pantheon. There is no stress, no fear of failure. Success is guaranteed. When we show it to our audience, we revel in the astonishment and the compliments of admirers who are unaware they are looking at a design that precedes us. Rather than be critical, this audience admires our skills. If they are photographers, they long to do the same and create their own trophy shots collection.

In landscape photography, all we need is to find the same location, compose the image the same way, and process the capture to get the same look. The recipe is in the original image. If we need help, there are countless tutorials to help us along the way. It is no different than making something by following a template or a set of instructions.

The reason I understand this process well is that I have done it multiple times. I have to add that it provided me with much satisfaction. I found pleasure in proving to myself that I was as good as those who came before me. Until one day I tired of it and discovered that my own images, those I created without following a previously existing design, were more pleasing to me than the copies. They provided me with a different form of excitement. A satisfaction that was internal rather than external.

Tradition and common sense say that we learn that way. We certainly do. But the most important lesson is learning to stop doing it. There is no harm in doing. The only harm is in not stopping to do it. Because by not stopping, we do not give our imagination a chance to run free. We do not seize the opportunity to use what we learned for the sake of our own art. We do not put what we learned to the service of our own vision. In fact, this vision, our vision, is never given the opportunity to be born, to become part of the real world. It remains a shadow, limited by its superficiality. Far from being visible to all because it is accessible only in our mind, or through our verbal description. This does not work because creativity calls for personal expression. To deny it is to deny our art a chance to exist. Many are those who carry in their mind tantalizing images that will never be seen.

Some locations do not lend themselves to repeatable designs. Because the water patterns on the Death Valley Playa change constantly, it is not possible to duplicate this image.

Conclusion

A classical photograph is a blueprint. We re-create the designs of previous artists because we are inspired by the work of those who came before us. After all, it is because of their work that we chose to learn photography, to practice the medium they were practicing. Their photographs are our inspiration. All artists are inspired by previous artists and therefore it is logical that being in love with their work, we adopt and use the designs they created. These designs take different forms depending on the medium. In photography, it can be the location, the composition, or the color or contrast palette. In painting, it can be the fracture, the rendering of the subject as realistic or abstract or the color palette. In dance, it can be the poses, the movements, the choreography. In trapeze, it can be the aerial choreography, the use of accessories, the ways of holding the trapeze such as by the hands, feet, or the teeth using a special apparatus. In any medium, it can be following the tenets of a specific art movement and interpreting this movement in a style similar to that of a previous artist.

The work of those who came before us is influential in generating our passion for photography. As we move forward with our careers, we find it difficult to distance ourselves from their work. There is a good reason for that. It is because their work acts as powerful guidance showing us what is good photography. The photographs of those who came before us are models of successful images done to the highest level of artistic and technical quality. They are the demonstration of mastery by artists whose work has brought them worldwide fame. They are good, both for us and for photography at large. All mediums need such work, such artists, such acknowledged masters.

Yet what is fascinating in art is an artist’s ability to create new designs. What makes an artist’s work compelling is the creation of images that have not been seen before. Seeing images indicative of the emergence of a brand-new vision is an unforgettable experience. It is being confronted with a new way of representing reality, a new way of seeing the world.

Creating art, ‘real art,’ means creating work that is new, never seen before, and entirely ours. This is how we create an artistic identity, what is commonly referred to as an artistic style. By attempting to match the designs of those who came before we are denying our own artistic identity a chance to come to life. We are so involved in attempting to find their vision that we deny our own vision a chance to be born, bloom, and grow. We become so engaged in re-finding the vision of previous artists that we do not give a chance for our vision to come out and to express itself. In practice, instead of becoming ourselves, we risk the chance of becoming them.

Early in our careers, it is difficult at first to create new designs because each time we try, we bump into the designs of those who came before. Two facts collide the fact we are new to this and the fact so much has been done before us. To create something new, we face a difficult choice: redo what has been done, or venture into the unknown with our own work and try to create something new now. Either option is unrealistic. We cannot recreate all that has been done because it would require many lifetimes. Venturing immediately into the creation of new work without any knowledge of what has been done before is likely to lead to unconscious recreation of what already exists. So, what are we to do? This problem is not new. Past artists dealt with it and future artists will have to. I propose that the best solution, the one I was taught at the Beaux-Arts, is to create work and listen when someone remarks that our work ‘looks like another artist’s work’. This situation will happen because it happens to all artists. When it does happen, we need to look up this artist’s work and learn all we can about him or her. We need to study their work, all of it, and learn what they did, where they stopped, and where they did not venture. It is important to study the artists whose work resembles ours.

We have to do it to learn what they have not done and proceed to create work that goes beyond theirs.

Summary

In this essay, I explained why the designs of previous artists can be used as blueprints, or models, or our own photographs. Instead of creating new designs, we have the option of using the designs created by the photographers who came before us. The problem is that if an artist re-creates the designs of a previous artist, they run the risk of becoming that artist instead of becoming themselves. This is antithetical to the concept of art because creating art means creating work that is unique to us. The solution is to learn as much as possible about those who came before us, find out what they have not done, then proceed to create work that goes beyond their work, work that is unique to us.

What’s Next?

In my next essay, I will explain how Pye defines workmanship and apply Pye’s concepts of Workmanship to fine art photography.

About Alain Briot

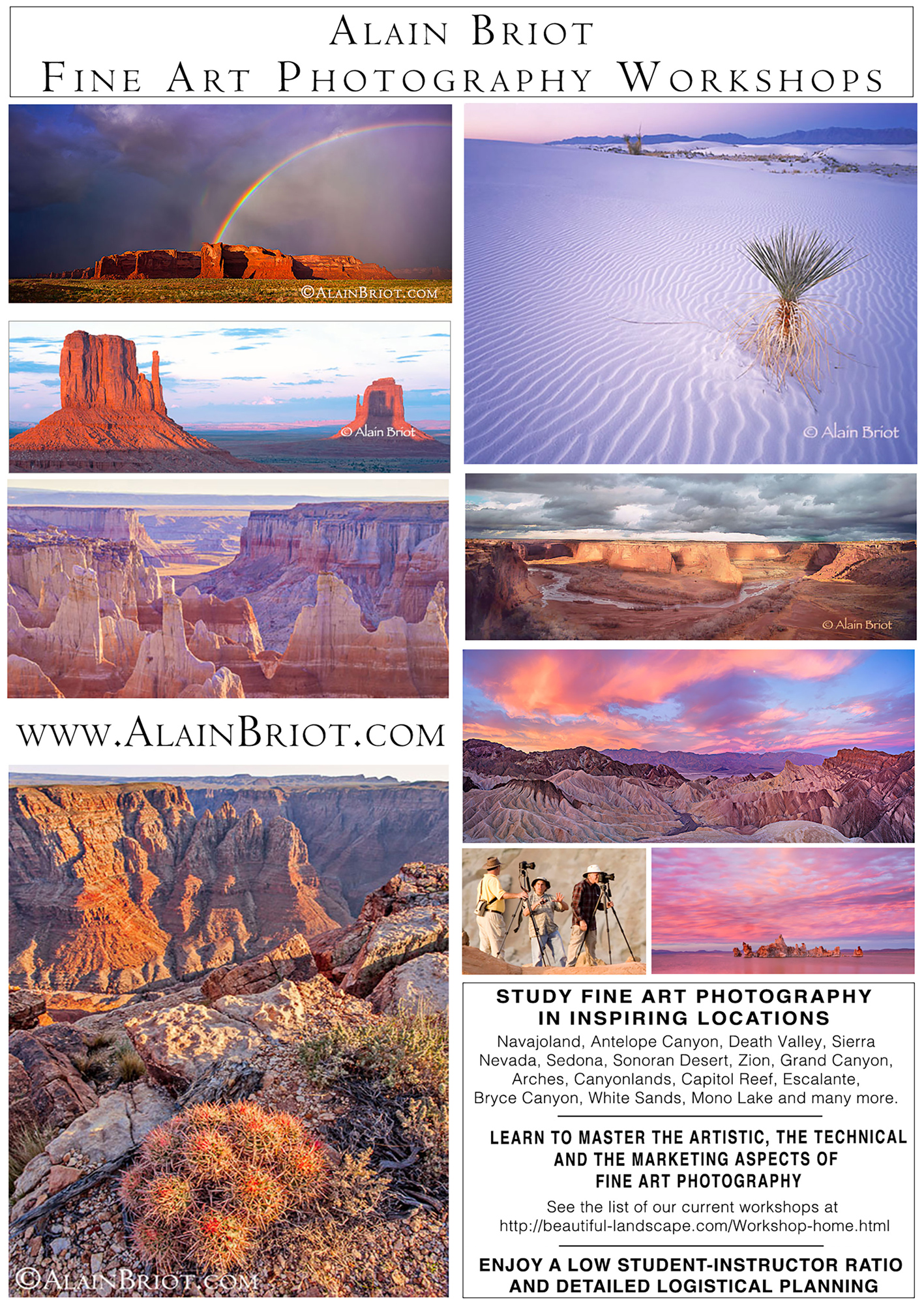

I create fine art photographs, teach workshops with Natalie and offer Mastery Tutorials on composition, image conversion, optimization, printing, business, and marketing. I am the author of Mastering Landscape Photography, Mastering Photographic Composition, Creativity and Personal Style, Marketing Fine Art Photography, and How Photographs are Sold. All 4 books are available in eBook format on our website at this link. Free samples are available so you can see the quality of these books for yourself.

You can find more information about our workshops, photographs, writings, and tutorials as well as subscribe to our Free Monthly Newsletter on our website. You will receive 40 free eBooks when you subscribe.

Studying Fine Art Photography With Alain and Natalie Briot

If you enjoyed this essay, you will enjoy attending a workshop with us. I lead workshops with my wife Natalie to the most photogenic locations in the US Southwest. Our workshops focus on the artistic aspects of photography. While we do teach technique, we do so for the purpose of creating artistic photographs. Our goal is to help you create photographs that you will be proud of and that will be unique to you. The locations we photograph include Navajoland, Antelope Canyon, Monument Valley, Zion, the Grand Canyon, and many others. Our workshops listing is available at this link.

Alain Briot

February 2022

Glendale, Arizona

Author of Mastering Landscape Photography,Mastering Composition, Creativity and Personal Style, Marketing Fine Art Photography, and How Photographs are Sold. http://www.beautiful-landscape.com [email protected]