Inspired By David Pye – Art Of Risk and Certainty

In the workmanship of risk, the quality of the result is not determined but depends of the judgment, dexterity, and care that the maker exercises as he works.

David Pye

Introduction

In the two previous essays, I looked first at David Pye’s concept of design and second at how the designs of previous artists influence us. In this third essay, I look at David Pye’s concepts of workmanship of risk and workmanship of certainty. I also draw conclusions about how these two concepts influence artists to either play it safe by re-creating pre-existing work or to take risks by creating new, never-seen-before work.

Workmanship of Risk and Workmanship of Certainty

Workmanship is the manufacturing process through which an object is created. This process can be manual, mechanical, or a combination of both. For David Pye there are two different types of workmanship: the workmanship of risk and the workmanship of certainty. The difference between workmanship of certainty and workmanship of risk is that in the first instance the final outcome is known while in the second the final outcome is not known.

Workmanship of certainty is commonly used in industrial production. A prototype is made and afterwards the object is produced by machines in an industrial production setup. When they come out of the production line each item is similar. No differences are present from one to the next. By contrast, the craftsmanship of risk is used in manual production with hand tools. If several items of the same design are created there will be visible differences between them due to the fact that hand tools do not leave the same marks twice.

The workmanship of risk involves a constant risk of failure. The workmanship of certainty on the other hand guarantees a known outcome. However, the differences do not end here. In the workmanship of certainty approach, the craftsman/artist knows what the final item will look like before starting production. The outcome is certain and success is guaranteed, hence the appellation ‘craftsmanship of certainty.’ In the workmanship of risk approach, the craftsman/artist does not know what the final item will look like until production is completed. The outcome is uncertain and failure is a possibility, hence the appellation ‘craftsmanship of risk.’ Success versus failure. The two approaches are poles apart, antithetical to each other.

Another way to look at these two approaches is by saying that the workmanship of risk is motivated by creativity while the workmanship of certainty is motivated by safety. When using the workmanship of risk, the craftsman/artist is open to the final item being different from his original expectations and the process offers the possibility of making creative changes during the creation of the piece. When using the workmanship of certainty, the craftsman/artist wants to make an exact copy of the original design and the process guarantees that each piece will be identical.

There is another aspect to this, a caveat if you will. Separating the two types of craftsmanship as being done by hand or by machine is not enough. Pye points out that creating something by hand instead of by machine does not automatically qualify as workmanship of risk. This is because when working by hand a jig can be used to control the hand tool. A jig, another of Pye’s cryptic terms, is a device that controls the action of a hand tool. It is something that guides the tool in order to control the outcome of the work. In woodworking a jig can be a guide that controls the movement of a planer keeping it at 90 degrees to the wood being worked on for example. With photography, it can be a plugin, an action, artificial intelligence input, or any preset operation that guarantees a known result.

Regardless of the medium used, when using a jig, the outcome is predefined. Certainty is present even though a hand tool is used. In photography, using a preset, a plug-in, an action, artificial intelligence or any automated process, is comparable to using a jig. When an artist uses an automated process uncertainty is removed from the outcome. The artist knows what they are going to get before they apply the plug in, the action or whatever automated process they are using. In that situation they are approaching the work with a craftsmanship of certainty mindset rather than a workmanship of risk mindset. For all practical purpose the risk is removed because they know what the outcome will be like.

Pye’s Concept of Workmanship Applied To Photography

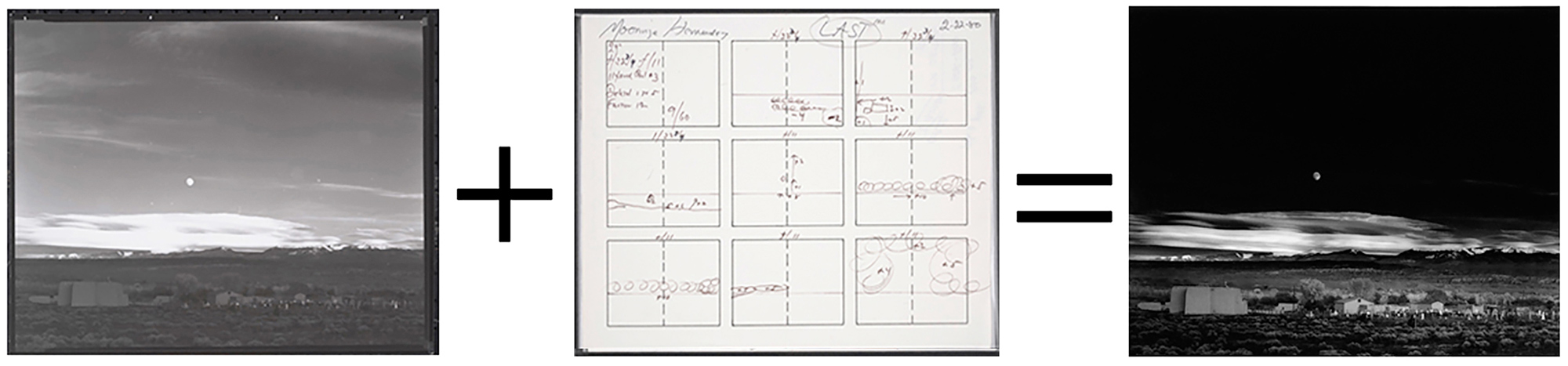

Does the creation of a photograph call for a craftsmanship of risk or a craftsmanship of certainty? To answer this question let’s see how photographic creative practices can be interpreted in the light of Pye’s philosophy. I am primarily interested to compare the approach taken by film and digital photographers. One of the most famous film landscape photographers is Ansel Adams. Adams’ concept of visualization is well known, and for a good reason: it is still valid today. For Adams, and I quote, ‘The negative is the score and the print is the performance.’ What Adams means is that the negative, the film on which the image was recorded in the camera, contains the necessary information to create a fine art print that expresses the photographer’s pre-visualization. Pre-visualization is Adams’ term for the process of expressing what the artist saw and felt in the field. Back in the studio, the negative is developed and a print is made. This is when the performance takes place. It is during the creation of the print that the artist creates a rendition of the score/negative, which exhibits what he or she saw and felt in the field.

Applying Pye’s terminology to Adams’ concept is illuminating. If the score is the origin of the print, then the score is the design. If the print is the outcome of the score, then the print is the workmanship. When Pye’s and Adams’ concepts are combined, the negative is the design, and the print is the craftsmanship. We also see that there is nothing in the negative that describes the final print precisely. To become real and visible to all, a physical print has to be made from the negative. Doing so involves a translation of what the artist saw and felt in the field into shades of grey on paper, using the negative as the intermediary device. To become a print the negative has to go through a radical transformation which can only be done by the artist.

It is therefore clear that Adams’ score/negative concept is just as platonic as Pye’s design concept. What the negative captured are shadows. Only when printed will it show its true potential, its true capabilities, its true content. Only then can the audience see what the artist saw and felt, what the artist pre-visualized in the field.

Notice that this pre-visualization is not a pre-visualization of the negative. It is a pre-visualization of the print. Hence a step is ignored in the process of pre-visualization because, in his mind, the artist goes directly from the scene in front of him to a print on paper. However, this print cannot be created before a negative, or today a raw file, is created. The negative, or the raw file, is the intermediate step between the original scene and final print. It is indispensable and yet is it not visualized.

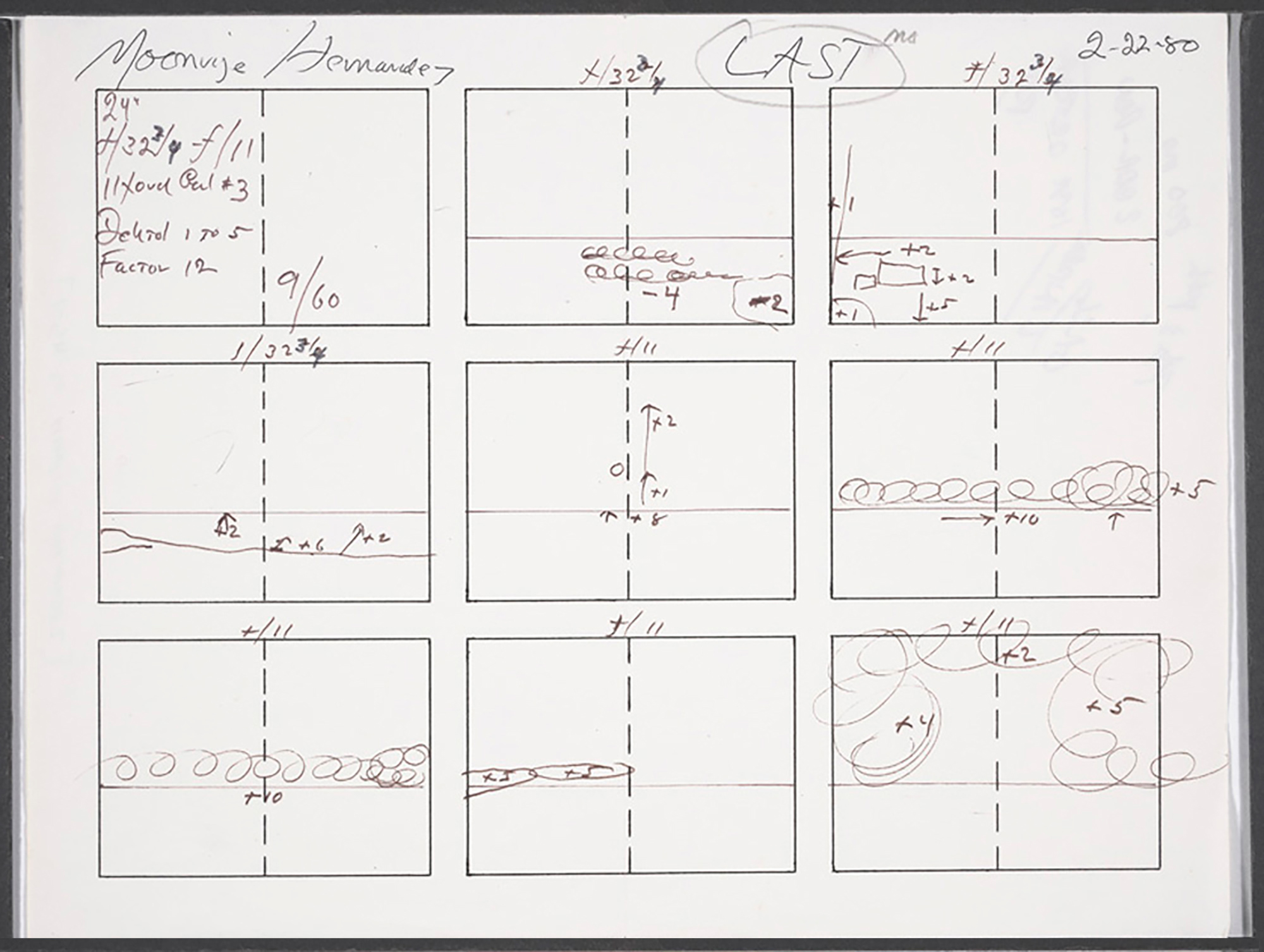

Yet the negative requires vision just as much as the final print. Making a negative that has all the artist needs to create the print he visualized requires a lot of work on the part of the photographer. It is not an accidental creation. It is a carefully monitored process. The negative must be exposed precisely according to the zone system, an approach to exposure invented by Adams to give him control over the creation of the negative so that it captures the precise range of tones he wants to have in the final print. The negative has to be developed precisely, according to specific variables set by the exposure. This means that exposure and development of the negative must work in tandem. If we expose the negative a certain way it should be developed a certain way. Development is dictated by exposure. This is a technical process, not an artistic process. The terms used to indicate the exposure and development required are technical: N, N+1, N-1 meaning normal, long and short exposure and development times. The temperature of the development baths has to be precise. The duration of the development has to be timed exactly, in minutes and seconds.

The process is highly technical. Yet the desired outcome is artistic because the print is an artistic creation. No two prints can be exactly alike because small variations of exposure, dodging, burning, toning, drying and more will inevitably creep in. This is a manual process after all, not a mechanical process, even though machines such as an enlarger, timer, automated washing tanks, etc. are involved. These machines do not create the negative or the print. They support and facilitate their creation. The process is helped by the presence of machines but the process is not controlled by these machines. It is controlled by the artist. It is the hand and the mind of the artist that creates the negative and the print. It is the artist who, at any time, is free to modify what the machines do.

From Film to Digital

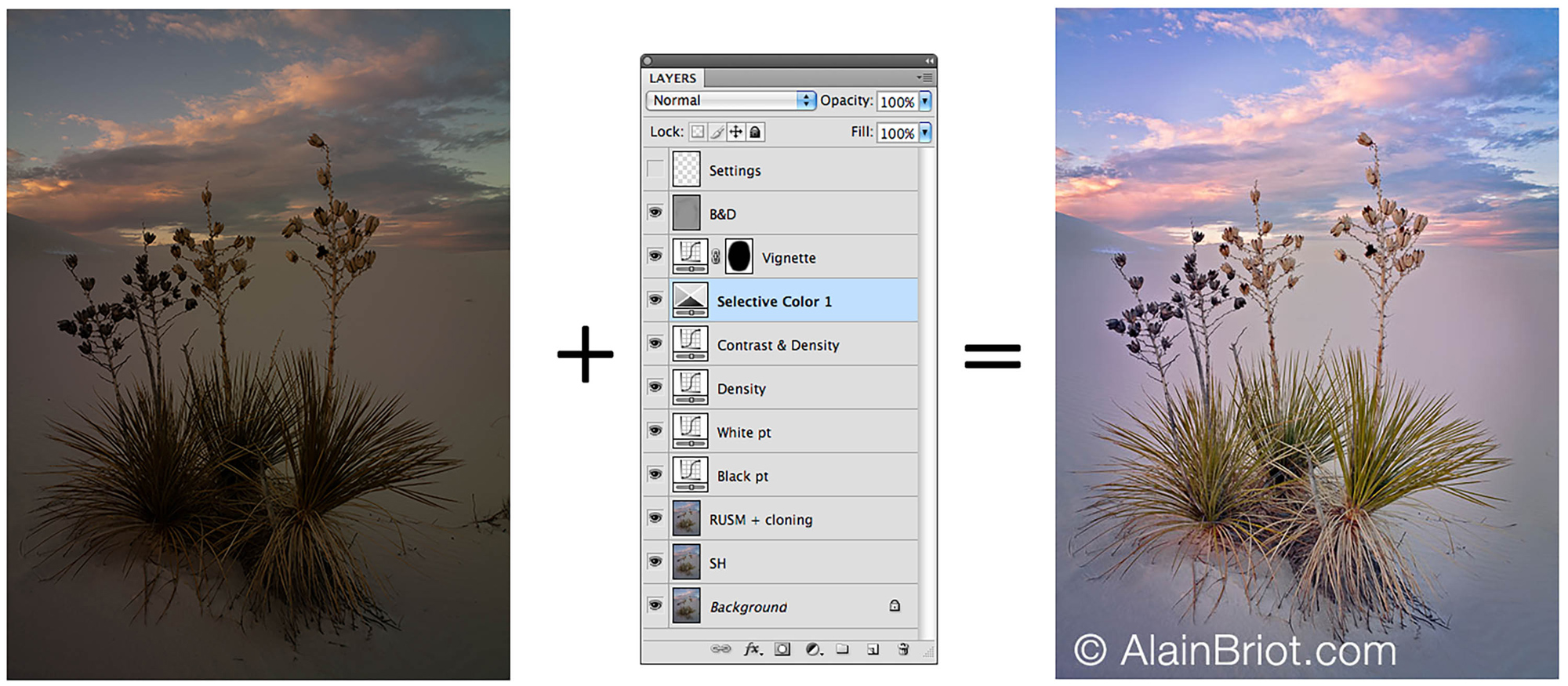

Today digital photography has replaced the negative with the raw file. We can therefore say, to paraphrase Adams, that the raw file is the score and the print is the performance. However, the raw file does not fall under the same technical limitations than the film negative. A raw file is much more forgiving, more malleable, than a negative. The ever-increasing dynamic range of digital cameras means that calculating the exposure precisely is no longer an absolute requirement. The same raw file, exposed to capture shadow and highlight details in the scene, can be converted a number of different ways. This is very different from negatives for which exposure and development had to be closely related. A raw file capture, therefore, removes the risk from the photographic process: the risk that the raw file will not give us the freedom to create the print we see in our mind. Unless the raw file is extremely under or over exposed, we will be able to interpret it pretty much any way we want. Even if the exposure is dead wrong, we can combine several raw files and create a composite image that has the exposure range we desire.

This means two things. First, Adams’ score and performance concept continues to be valid and applicable to today’s digital capture. Today the raw file is the score and the inkjet print is the performance. Second that pre-visualization is no longer limited to fieldwork, to the time at which the image is captured. Because the same raw file can be interpreted, or ‘performed,’ in a variety of ways, visualization now extends to studio work. We can even give this new double visualization approach two different names: pre-visualization in the field and post-visualization in the studio.

Adams’ concept was the main model for creative photography in film days. However, it only applied to black and white photography because the zone system could not be fully applied to color film. Today digital cameras capture raw files in color and the choice of black and white or color conversion is done in the studio, after fieldwork is completed. Deciding that an image will be color or black and white ‘after the fact’ adds an additional creative opportunity. It is another aspect of the creative process where post visualization can take place. The final print can be pre-visualized in black and white in the field and post-visualized in color in the studio, or vice versa. The final image can even be part color and part black and white. Furthermore, countless additional post visualizations can be done, all made possible by digital technology. Film pales in comparison to the number of creative outcomes offered by digital capture.

I asked earlier whether Adams’ approach uses the workmanship of risk or the workmanship of certainty. The answer I believe is that it is a combination of both. There is no doubt that Adams’ goal was to express his vision of the world through his photography. This endeavor contains risk because he did not have a model to follow. He could only follow his own vision, his own design, which as we saw previously is nothing more than shadows and not reality itself. Adams was however practically minded and realized that creating this vision on the basis of shadows would not generate success. So, he created the zone system to take his vision from idea to reality. The zone system allowed him to control the main challenge presented by film, namely capturing the full range of tonalities found in outdoor scenes lit only by sunlight. The zone system represented the craftsmanship of certainty in an endeavor that, overall, was based on the craftsmanship of risk.

Another way to put it is to say that Adams’ art was risk but his technique was certainty. The expression of his vision via photographic images offered no guarantee of success. Each new photograph hovered between success and failure until the final print came out of the darkroom. There was no guarantee of success in the expression of the pre-visualization in his mind. However, because of the zone system, there was a guarantee of success in the capture of the tonalities through which this vision would come to life.

This careful approach, mitigating risk and certainty, continued when the negative was printed. The first series of prints were test prints whose goal was the creation of a master print that featured Adams’ pre-visualization, what he saw and felt in the field. When a master print that expressed Adams’ experience was created, Adams proceeded to write a ‘recipe,’ on a sheet of paper on which were written all the technical information Adams needed to recreate the master print as many times as he liked. The creation of the first master print used the craftsmanship of risk. The creation of the fine art prints afterwards used the craftsmanship of certainty. The print recipe acted as a darkroom jig, allowing Adams to follow the step-by-step approach he devised during the creation of the first master print.

Today the digital master file acts as our master print. The master file contains all the adjustments, manipulations, and changes we made to the raw file. It is followed by test prints and adjusted to compensate for variations between what we see on screen to what is printed on paper. The master file takes a significant amount of time and work to create, just like it took Adams a significant amount of time and work to create his master print. However, once created, the master file acts as a jig. All we have to do to create a fine art print is load paper in the printer and press the print button. Here too, with digital as with film, we have a combination of craftsmanship of risk and craftsmanship of certainty. The master file is done using the craftsmanship of risk. Nothing is certain until a satisfying master file and test print are created. Afterwards, the production of additional prints uses the craftsmanship of certainty. We know that each print will be the same as the original test print because the master file contains all that is needed to create a perfect print each time.

The Desire For Certainty

Pye’s opposition of risk and certainty is insightful. On the one hand, risk is desirable because it leads to the creation of unique pieces. On the other hand, certainty is also desirable because it brings piece of mind, guarantees a known outcome, and facilitates the production process.

The point can be made that all creation involves risk, whether we create something by hand or by machine, and whether the work is done at home by one person or by many in a factory. Artists get tired. Factory workers go on strike. Hand tools can break or can be setup improperly resulting in the production of substandard quality pieces. Machines can suffer mechanical failures. An assembly line can get jammed, be inefficient or even destructive to men, machines or both. Both artists and production workers get sick, do not feel well, or see their performance affected by personal problems. These risks are inevitable and they are present in both handmade and factory-made settings. This means that absolute certainty does not exist in either manual or mechanical production.

If certainty is something human beings aspire to, can we ever get rid of the desire for certainty? If we believe Darwin, survival is reserved for the fittest, implying that human existence hinges on overcoming risk. If so, controlling risk is an achievement. Similarly, engaging in activities that do not involve risk is something we look forward to. It is something that brings peace of mind because the outcome is certain.

I can see how the desire to minimize risk plays out in the arts. No artist or craftsperson starts working on a new piece or a new project without some certainty of success. If artists believed, before starting the work, that they are going to fail, they would not begin. This is a strong argument for the belief that most of us prefer to work within a certainty-based system. For sure, artists never know exactly what the outcome will be like. In that respect there is a risk. But they do believe that whatever the outcome it will not be a failure, and in that respect, there is a certainty.

Summary: Where Are We Now?

So far in this series, we saw that a photograph is a design and that this design consists of the combination of location, composition, and processing. We saw that the photographs of those who came before us can be approached as designs that can be used as models for our own photographs. We also saw that most of us start by creating images that are inspired and influenced by the designs of those who came before us but that, over time, we make small but constant modifications to these models. This process can take longer for some than for others. Finally, we saw that we can approach the creation of a photograph by using a craftsmanship of certainty or a craftsmanship of risk approach. The former guarantees a known outcome and the latter is prone to the vagaries of the creative process. However, because a work of art is by definition unique, using a craftsmanship approach that guarantees uniqueness is desirable, even if it brings with it an undeniable amount of risk and uncertainty.

Pye’s concepts of workmanship of risk and of certainty influence artists to either play it safe by re-creating pre-existing work or to take risks by creating new, never-seen before work. In the next essay I will look at the implications brought about by embracing the workmanship of risk or the workmanship of certainty when creating art and specifically fine art photographs.

About Alain Briot

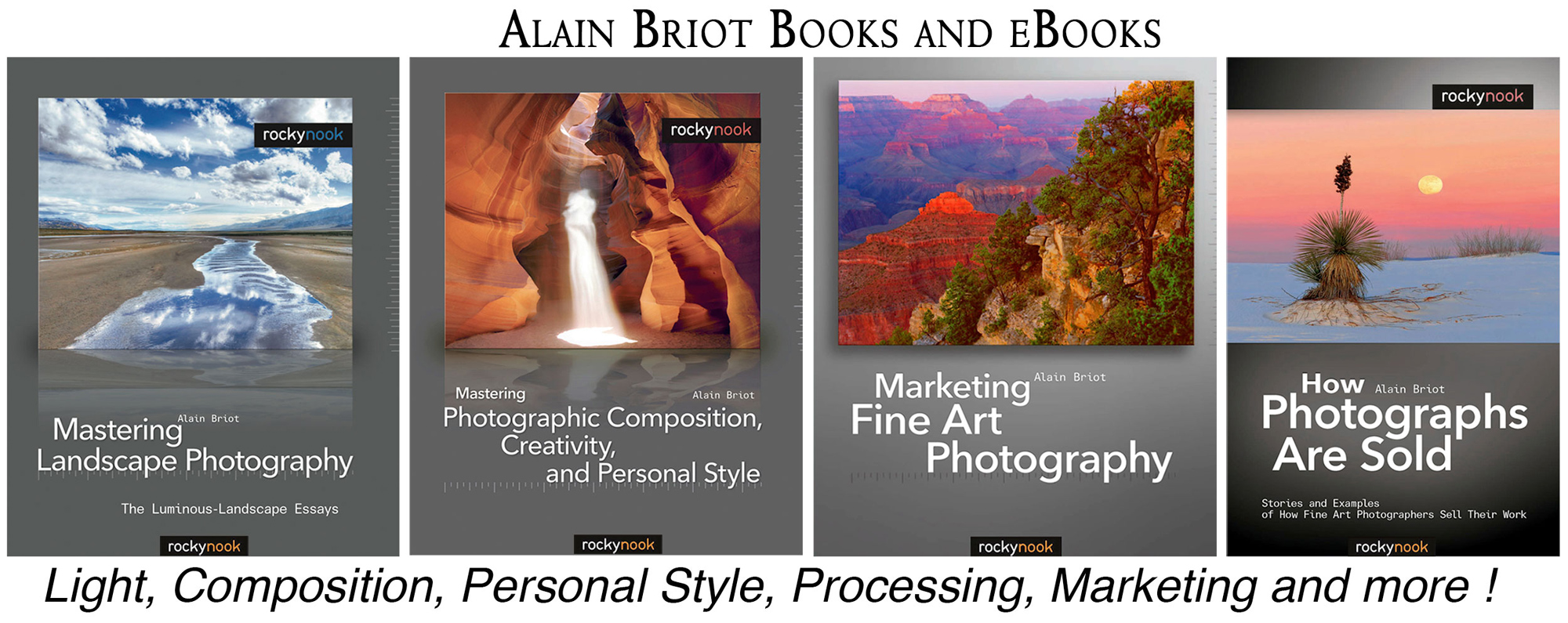

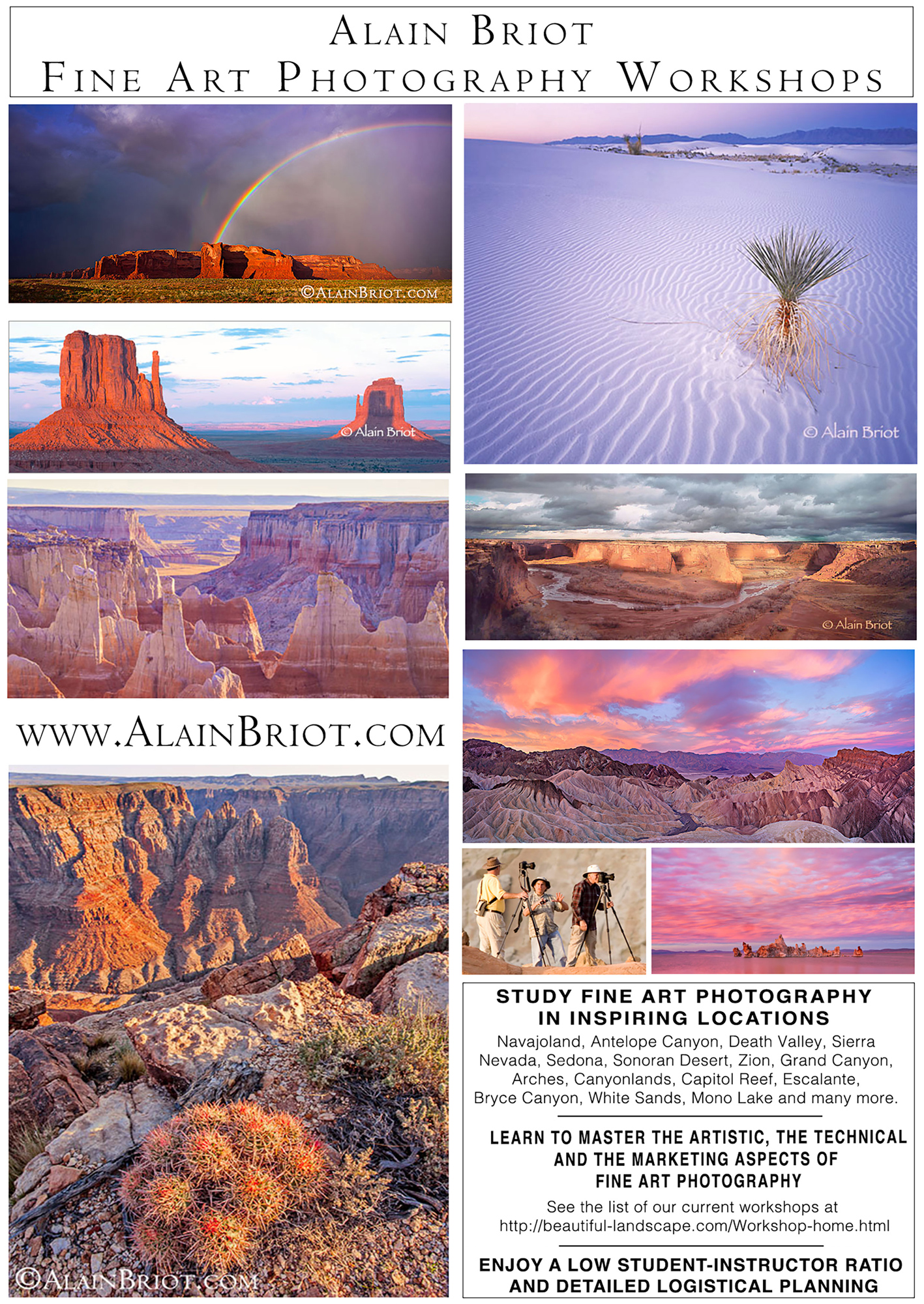

I create fine art photographs, teach workshops with Natalie and offer Mastery Tutorials on composition, image conversion, optimization, printing, business, and marketing. I am the author of Mastering Landscape Photography, Mastering Photographic Composition, Creativity and Personal Style, Marketing Fine Art Photography, and How Photographs are Sold. All 4 books are available in eBook format on our website at this link. Free samples are available so you can see the quality of these books for yourself.

You can find more information about our workshops, photographs, writings, and tutorials as well as subscribe to our Free Monthly Newsletter on our website at http://www.beautiful-landscape.com. You will receive 40 free eBooks when you subscribe.

Studying Fine Art Photography With Alain and Natalie Briot

If you enjoyed this essay, you will enjoy attending a workshop with us. I lead workshops with my wife Natalie to the most photogenic locations in the US Southwest. Our workshops focus on the artistic aspects of photography. While we do teach technique, we do so for the purpose of creating artistic photographs. Our goal is to help you create photographs that you will be proud of and that will be unique to you. The locations we photograph include Navajoland, Antelope Canyon, Monument Valley, Zion, the Grand Canyon, and many others. Our workshops listing is available at this link.

Alain Briot

March 2022

Glendale, Arizona

Author of Mastering Landscape Photography,Mastering Composition, Creativity and Personal Style, Marketing Fine Art Photography, and How Photographs are Sold. http://www.beautiful-landscape.com [email protected]