How Photography on Safari Has Changed

Photographing on safari has changed and to say that it has gotten easier is an understatement. It’s night and day from my first safari over 20 years ago. Even in just the last 10 years, so much has changed about going on safari including technology, comforts, and wildlife.

On my first safari in 1997, I took two film cameras and 60 rolls of film in two lead-lined bags. When I started selling safaris almost 10 years ago, I had a backpack full of digital camera gear plus laptop and that totaled 30 pounds. For the safari I’ll lead this February, my camera kit weighs 10 pounds – yet has much higher image quality, incredible autofocus, and cards that equal over 100 rolls of film and fit in my pocket.

Cameras have gotten better in almost every way: more pixels, sharper optics, more precise autofocus, and other features like video. Mirrorless is a huge win for safaris because of its lighter weight. Autofocus performance remains a slight weak spot but, with practice, recent models give superb results (rumors of Sony expanding the A9’s face-detection algorithm to include animals are particularly exciting). Even something as “old-fashioned” as manual focus has gotten easier: both SLRs and mirrorless bodies now offer manual focus tools on their displays to show which edges in your image are sharp — critical for that cat peeping through tall grass that autofocus systems still struggle with. Recent models are adding IBIS and that leads to an even higher hit rate.

Memory cards have gotten cheaper (and don’t require lead bags at the airport x-ray!). I used to advise clients to bring a couple of memory cards plus hard drives for backups and we would download every day and reformat. Now I skip the bulk and weight and advise them to bring lots of memory cards and don’t overwrite them. But if you do want a hard drive backup with you, devices like Samsung’s T5 SSD drive are small, have enormous capacity, and weigh almost nothing.

Smartphones used to be dismissed as toys but even “serious” photographers now use them for a backup or at least quick, grab shots. There are even high-quality accessory lenses for the iPhone. I own both wide-angle and telephoto lenses from Moment that fit in a shirt pocket at the same time. There are, of course, plenty of apps for processing photos on your phone but don’t ignore the rest of a smartphone’s utility: there are wildlife and birding apps for identifying species and logging sightings too. Why would you bring your bulky paper camera manual? Put that PDF on your phone instead. You’re bringing more but carrying less.

Back in 1997, I was in a backpacking tent and sleeping bag on the ground. Now, the camps and lodges in the parks compete and leapfrog each other frequently so that food and amenities are constantly improving. Even in the most remote areas of the Serengeti, there are private, hot showers and flush toilets in your tent and beds with nice duvets (really, they’re canvas cabins – not tents). The chefs are even aware of special diets so clients who are vegetarians or dairy or gluten-free can eat well. Planning for charging your camera and laptop batteries used to be a concern. Now if your tent doesn’t have its own power outlets, they’re in the common areas with plenty of outlets to share.

Some camps even have WiFi. I have mixed feelings about this since being forced to be off the grid is good for the soul but there’s no denying the benefits if you need to be connected. Sharing an amazing sighting online with the caption, “Happening now in the Serengeti” can create a real-time sense of connection with your friends back home.

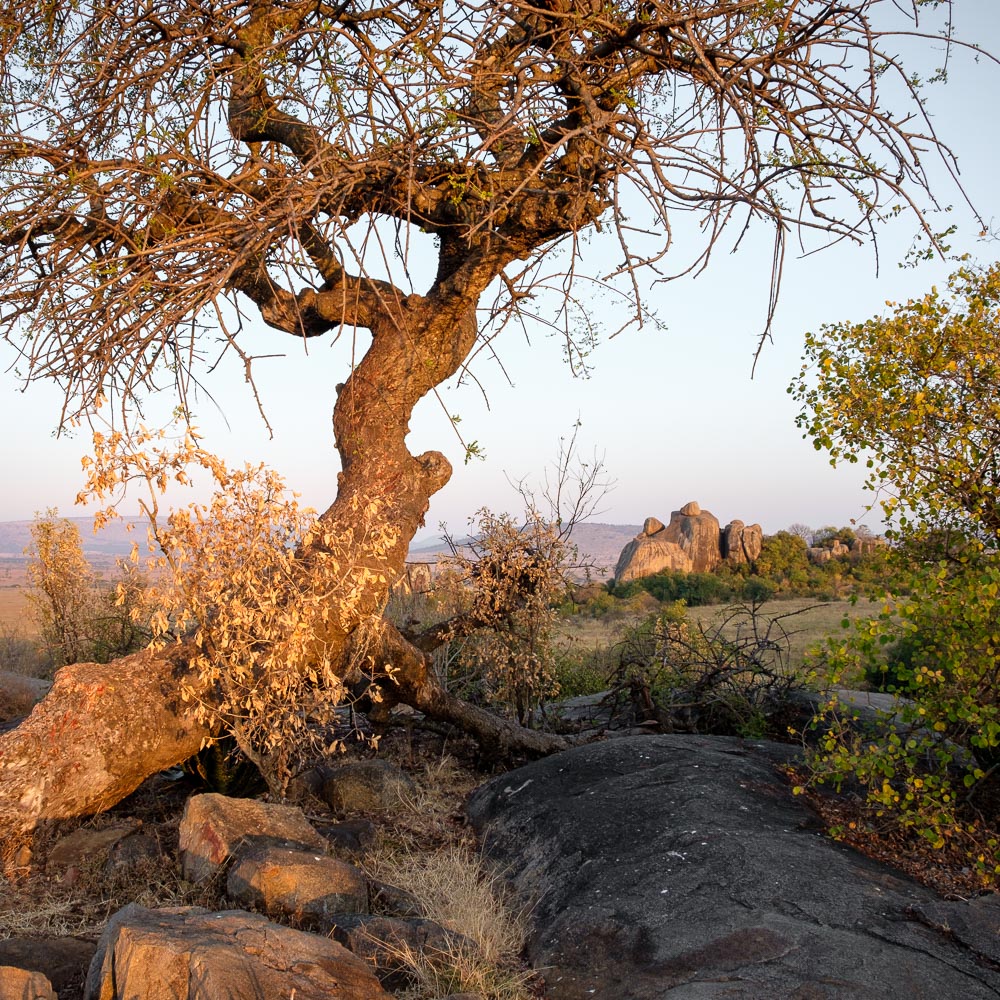

When I was in Tanzania in 1997, I was off the grid for 5 weeks and out of touch with family and friends until I returned. Even just a few years ago, I had to buy a local mobile phone SIM and climb a kopje near camp in the Serengeti to the “cell phone tree.” That’s the tree the camp staff use to call their family; if they stand there and point their phone the right way, they get one bar of signal. But now, it’s amazing to call home from camp using WhatsApp and hear a crystal-clear connection.

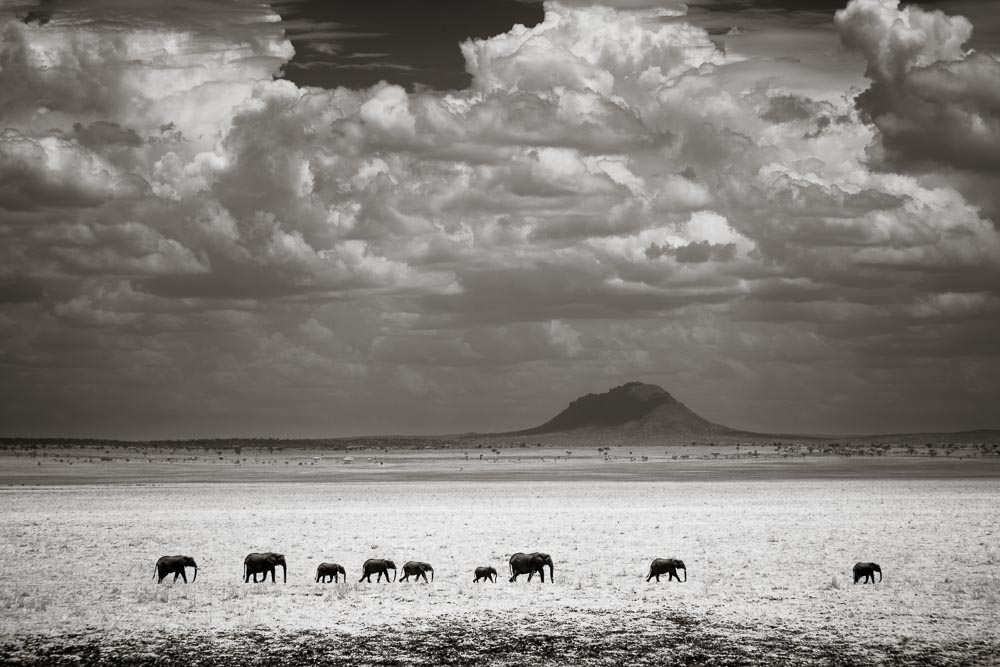

So, what hasn’t changed in all this time? Great safari photography is still some of the most challenging you can do. You need to be able to respond quickly to emerging situations with subjects that aren’t interested in posing for you. You need to know your camera’s buttons and dials intuitively. And you still need to be patient: once I waited 2.5 hours for a herd of wildebeest to cross the Mara River. Was it worth it? Resoundingly, yes. Witnessing an iconic event like the great migration will send shivers down your spine and I came away with many shots I’m happy with.

One positive trend I’ve seen is a change in attitude towards huge lenses with a long reach. While close-ups and advice to “fill the frame” are great, I’ve always felt this was driven by photographers who are more interested in seeing what high-end gear can do rather than make beautiful photographs. Now I see many people happy with mid-range zoom lenses (e.g. 70-200mm) that show wildlife within a larger scene. It depends on the scene of course. Long lenses are obviously useful and zoom lenses with good ranges for safaris have improved. Canon’s 100-400mm is a common lens to see and their 200-400mm with the built-in 1.4x converter is considered a perfect safari lens.

Sadly, one thing that has deteriorated over time is the abundance of wildlife. You will still see many – just last October my vehicle was surrounded by a herd of 70 elephants – but poaching is still rampant across the continent. Tanzania has seen some of the worst elephant poaching and, by some estimates, they have lost 70% of their elephants in the last 10 years.

When it comes to photo tours, the marketplace has exploded in the last 10-15 years and now you can find a tour to almost any destination you want. But one thing that hasn’t changed is that an African safari is still a bucket list item for nature photographers. And whether it’s your first safari or your tenth, each one is a different experience.

Kevin Raber and I are discussing offering a safari in spring of 2021 and we’re gauging interest levels. If you’re interested in joining us to photograph these iconic landscapes and wildlife, contact me at [email protected] to be included on our safari list.

Dave Burns

December 2019

Boston, MA

Dave Burns is an award-winning photographer specializing in wildlife, travel, and landscapes. He has had a camera in his hand as long as he can remember and his favorite subjects range from the African savanna to the streets of Paris. His first safari to Africa in 1997 started a passion that led to several returns and, after 25 years in the software industry, he started selling safaris to other photographers in 2012. He now leads safaris two to three times per year. Classically trained in the black and white darkroom and the Zone System, Dave presently works digitally from capture to print. He was born and raised in the Washington DC area and now resides in Boston. His photographs have been exhibited in galleries in the Boston, New York, and DC areas and are part of numerous private collections. To contact him, check out www.daveburnsphoto.com.