How Long Do Art Movements Last?

Almost always, the men who achieve the fundamental inventions of a new paradigm

have been either very young or very new to the field whose paradigm they change.

Thomas Kuhn

Introduction – Difference Between Paradigms and Movements

In my previous essays, I talked about how paradigms shape our approach and perception of art. I reflected on how paradigms define what kind of art we create and what kind of art we like. Because the outcome of a paradigm’s influence is the emergence and the disappearance of art movements, the logical continuation of this reflection is to look at how long art movements last.

Artistic Paradigms Define How We Understand Art

Thomas Kuhn is the historian of science who coined the term paradigm shift to describe scientific revolutions. In his book, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1962) Kuhn explains that paradigms determine the way we approach and understand specific aspects of society. Kuhn looks at paradigms in the context of science. However, paradigms are present in all fields of human endeavor. This means there are artistic paradigms.

In the context of my series of essays, I look at how paradigms define the way we practice art. My point is that the existence of different art paradigms explains why we approach art in different ways. Each different paradigm asks different questions, sets unique challenges, defines different purposes, and changes the rules of the game for the artistic medium.

For example, Classicism is based on a different artistic paradigm than Modernism or Postmodernism after it. According to the Classical paradigm, the purpose of art was the representation of religious beliefs. Classical art was representational and flawless technique was important.

Modernism followed a completely different paradigm. According to the Modernist paradigm, the purpose of art was to challenge previously accepted aesthetic concepts. When Modernism came about, art shifted from representational to abstract. Modernism was concerned with expression and symbolism rather than with representing reality. Modernism was also not concerned with creating flawless paintings. For Modernism, any technique, from sophisticated to primitive, could be used to create art. As a result, Modernist paintings are far less realistic and polished than classical paintings. The goal of the modernist artist was not to make the subject visually recognizable or ‘pretty.’ Instead, their goal was to challenge accepted aesthetics and express the inner reality of the subject, its essence, and its symbolism.

Today the current paradigm is Postmodernism. According to the Postmodern paradigm, the purpose of art is the expression and representation of cultural concerns. In the Postmodern context, art is the vehicle used to express cultural and political concerns, issues, and challenges. During the shift from Modernism to Postmodernism, the purpose of art shifted from abstract to political. For Postmodernism, the goal of art is no longer to represent the essence of the subject but to use the subject as a vehicle for social change and for the expression of social concerns.

The Difference Between Paradigm and Movement

Because I am talking about artistic movements, it is important to address the difference between an artistic paradigm and an artistic movement to see which aspects of these two concepts are similar and dissimilar.

A paradigm is a shared set of assumptions, beliefs, or concepts that define how we perceive the world. An artistic movement is a set of tenets followed by a group of artists who share a common philosophy during a specific period of time.

Modern art as a whole, meaning the many different isms that emerged during the 19th and 20th centuries, had as a goal to challenge the aesthetic concepts established before the First World War. The goal was to create a new aesthetic based not on beauty but on personal choice. That was the paradigm at work in the modernist art world. How this paradigm was implemented by different artists gave birth to a variety of art movements. Each movement interpreted this paradigm differently. The originators of these movements all believed in the modern art paradigm. They all wanted to implement this paradigm in their work. However, each of them had a different idea about how to do this. The concretization of their individual ideas, their interpretation of the modernist paradigm, is what gave birth to artistic movements such as Impressionism, Post Impressionism Fauvism, Surrealism, Dadaism, Hyper-Realism, and more.

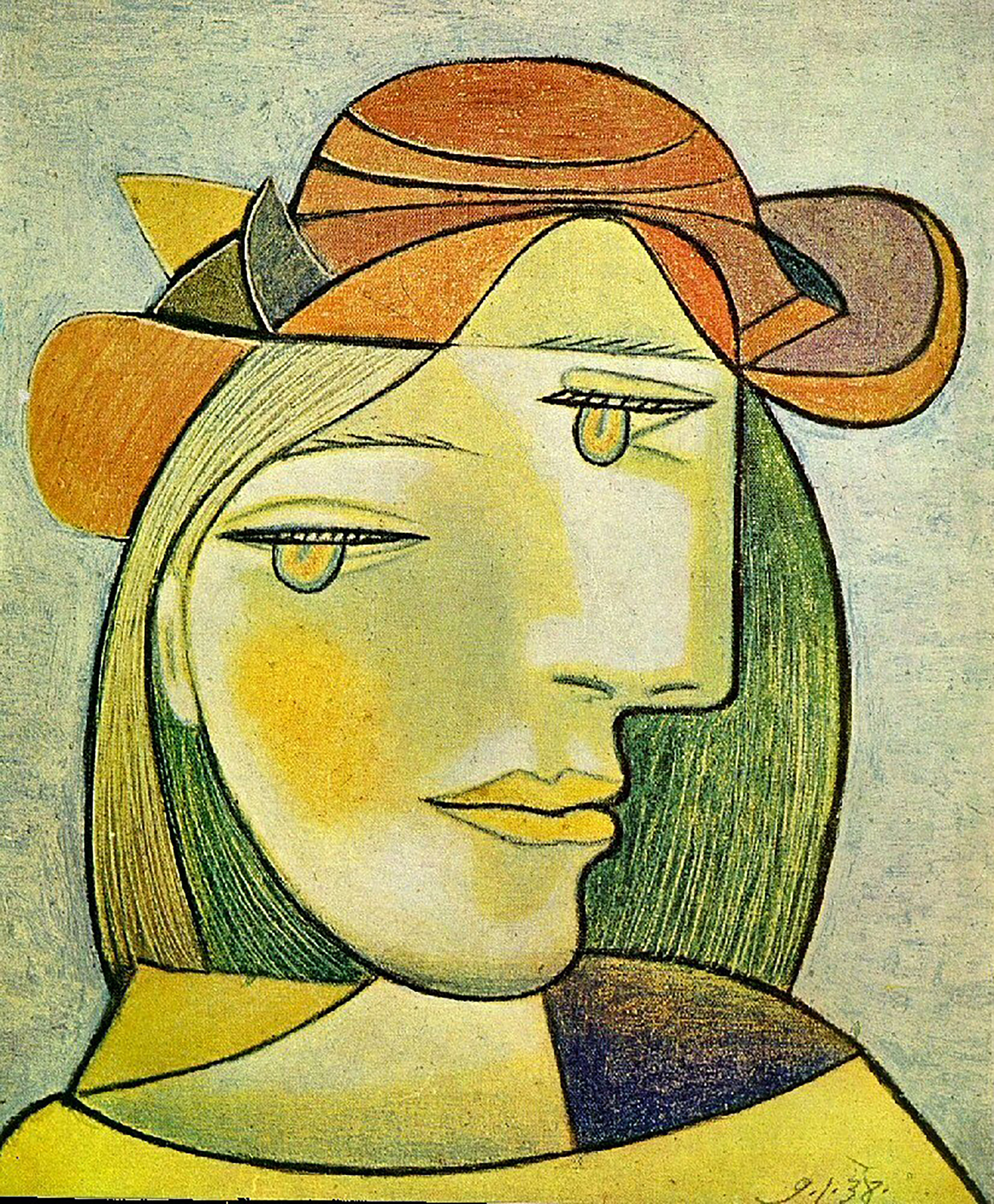

On top, we have a classical portrait of a woman, and at the bottom a modernist portrait of a woman.

The subject is the same, but the representation of the subject is completely different.

This difference is caused by the fact these two artists followed two different artistic paradigms.

Paradigm Shifts Are Spotty

Paradigm shifts take place in spotty fashions. They are not tidal waves. They are localized rainstorms. The whole cultural landscape does not get covered at once. Instead, one area gets flooded while other areas stay bone dry. During our workshops, when we tell students they cannot use tripods in Antelope Canyon, they get up in arms and tell us they cannot take good photographs of a dimly lit area without a tripod. They say Ansel Adams and other Modernist masters of photography all used a tripod to photograph such places. This is true. However, what is also true is that Adams and other Modernist photographers used 4×5 cameras, developed their film in chemical baths, and made prints in a darkroom under dim amber lighting. Do workshop students do all that? Of course not. They gave up on these aspects of film photography when they switched to digital. So why did they not quit using tripods as well? After all, excellent photographs, as good or better than film photographs, can be taken with a digital camera without using a tripod in Antelope Canyon. Successful examples abound. So, what is going on?

What is going on here is a spotty adoption of the new paradigm. Students did not quit using tripods because they only adopted part of the digital paradigm. They fully embraced certain aspects of digital photography (digital capture and processing in this instance) while refusing to stop using certain aspects of the previous paradigm (using a tripod). Part of their approach continued to follow the practices of the older paradigm. Because the reasons behind this decision were not examined, students are shocked when they find out they will be able to get great photographs even though they are not allowed to use a tripod in Antelope Canyon.

When we explain why good photographs can be created in low light locations with a digital camera and no tripod, (by using high ISO, wide f stops, auto stabilization, and so on) our teaching is met with suspicion. It is only when students see the outcome of their shoot on their computer and realize that their photographs are as good or better than if they used a tripod, that they believe that the techniques we taught them are accurate and effective. As they say, the proof is in the pudding and trust must be earned. Perhaps. However, most often it is time that is wasted when the proven effectiveness of a paradigm shift is questioned.

This attitude demonstrates the challenges and the problems that accompany a partial paradigm shift. Going back to the metaphor I used earlier on, I find the tidal wave preferable to the spotty rainstorm. I prefer to make a complete change than to change a few things here and there. If I make partial, localized changes, how do I know that I am changing the correct elements? The fact is I don’t. I am using a trial-and-error process, an approach I know to be costly of both time and money. If I make a complete change, no questions asked, I jump in wholeheartedly, right or wrong. If I win, I win big. Of course, if I lose, I lose big as well, but as we just saw the spotty change approach is no guarantee of failure either. So, the choice is between runaway success or inescapable failure, in whole or in part. I definitely prefer to take the option of full success. Whether it comes or not, at least I have the exciting prospect of looking up to it.

How Long Do Artistic Movements Last?

It is time to answer the question after which this essay is titled. Let’s start by stating the most important aspect first: how long an artistic movement lasts depends on the number of practitioners. Not just followers, but active practitioners. Not the number of people who like this style, or who collect it, but the number of artists who create art following the tenets of this movement. The practitioners of a movement are the artists who create art in the same style, or in a style comparable to or influenced by the founder of that movement. In the next essay we will see that while the style of these artists varies, the tenets of the movement they follow are always present in their work.

Prior to photography, a new artistic movement lasted one or two generations. One generation if there was a low number of practitioners, two if there was a large number of practitioners. However, a movement can last more than two generations if there is a huge number of practitioners. This is the case of photography whose number of practitioners exceeds those of any artistic movement. Because of the popularity of photography, how long a photographic movement lasts no longer follows the duration of previous art movements. Photographic movements may last much longer than any other art movement. They may also evolve in different ways than previous art movements.

This situation is uncommon and unexpected. Most of the artistic movements created during the 19th and 20th centuries lasted only as long as the original artist was alive. These movements started and ended during that artist’s life. While there were practitioners there was not enough to guarantee the survival of the movement past the death of the founding artist.

The popularity of an art movement is different from the number of practitioning artists who embrace this movement. A movement can be popular while having a small number of practitioners. This happens when only a small number of followers are artists, or because artists refuse to embrace a popular art movement. Artists tend to stay away from popular movements because they find them suspicious. Many artists believe that true art is reactive, counter-cultural, and thus by nature unpopular and of interest to a limited audience. As a result they look at popular movements with suspicion and often stay clear of them.

Most art movements do not outlive their creator. They disappear when they are replaced by a more popular movement. However, movements do not vanish right away. They fade before they disappear. They progressively lose traction and followers. They eventually become passé and are seen as historical events instead of contemporary trends. This is also true of style as we will see in the next essay.

Movements And Technology

Art movements are affected by technology. The availability of new technology is one of the factors behind the creation of new art movements. The emergence of Impressionism was in part fueled by new painting technology. The availability of tube paint, portable easels, and lightweight pre-stretched canvases made it possible for artists to carry their gear in the field and paint outdoors. This new technology not only gave birth to a new art movement, it gave birth to a new approach to painting: Plein Air. The literal translation of Plein Air is ‘in full air’ meaning it is done outdoors, in the landscape. Plein Air was a dramatic shift from the previous paradigm which was studio painting. At that time painting gear was cumbersome making painting outside of the studio impossible. Easels were heavy and could not be transported under one’s arm. Paints had to be ground daily in large jars using pigments and linseed oil making them impossible to carry in the field. Paintings took months to complete. Because the light had to remain the same during the creation of a painting, studio windows faced north because north-facing windows provide a light source that is the same from day to day having no direct sunlight. In comparison outdoors natural light changes during the day making it necessary to paint quickly, usually starting and finishing a painting the same day.

Digital photography brought comparable changes to film photography. The combined availability of digital capture, battery-operated laptops, flashcards, computer software, and other digital technology made it possible to capture and process images in the field.

This shift is similar to the shift painting experienced during the emergence of Impressionism. While photography could be done outside prior to the introduction of digital imaging, it was limited to capturing the image on film. The rest of the process, processing, and printing, had to be completed later in the studio. Today digital photography makes it possible to see captured photographs in the field. It is even possible to print in the field, or in a hotel room if one uses a portable inkjet printer.

In many ways, with the film paradigm, creating a landscape photograph was similar to a painter making a pencil sketch of the landscape outdoors then retreating to his studio to complete the oil painting. Just like in pre-impressionist times, film photography gear was heavy and difficult to carry in the field. 4×5, the medium of choice for artistic film landscape photographers, was originally designed for studio use. Field use was possible but challenging. The first view cameras were monorail, making field use difficult. The invention of folding 4×5 cameras made fieldwork easier while still far from ideal. Carrying a heavy metal or wood camera in the field was a challenge. The camera was heavy, and the many moving parts made it fragile and prone to breaking. The presence of bellows meant that windy conditions had to be avoided. 4×5 cameras were not waterproof therefore rain was the enemy. Sand was another problem. It got in the fine gearing mechanisms damaging them and occasionally rendering them useless.

Setting up, focusing, and completing all the required settings to take a photograph with such a camera was a feat that took only seasoned practitioners could complete successfully. Learning was deemed complete when all the mistakes had been made and all the successful solutions had been found. Success was not guaranteed until the film had been developed, making anxiety a constant companion of fieldwork. One never knew if a shoot was successful or not until one was back in the studio and able to look at the developed film. Even then there was the issue of printing the images successfully, another ballgame altogether.

How Long Do photographic Movements Last?

Compared to painting, photographic movements have uncanny durability. In fact, most photographic movements have lasted longer than any painting movement. This is due to the popularity of photography. Being the most popular artistic medium means it has the largest number of practitioners.

Landscape photography has the largest number of practitioners of any contemporary artistic medium. This is because today everyone takes photographs and this makes everyone a practitioner. For this reason, photographic movements are lasting longer than movements in painting, sculpture, or other non-photographic mediums have in the last 200 years.

There is no doubt that the large number of adherents to the f/64 Modernist landscape photography movement made it last longer than it would have if there had been a small number of followers. We did not see that with other non-photographic Modernist movements such as Dadaism, Cubism, Surrealism, Fauvism or others. The lifespan of these movements, in regards to practitioners, was relatively short, most of these movements lasting only the lifetime of their creator. In fact, they sometimes lasted less than that because some artists created several movements, going from one to the next as their careers evolved. Such was the case of Cézanne who moved from Impressionism to Post-Impressionism, to Fauvism and eventually Cubism.

Conclusion

Movements last as long as they are relevant. They end when they become passé and no longer significant. They terminate when new ideas emerge or when a new paradigm replaces them. Because this happens progressively, the end of an artistic movement can be seen as a transition, as the progressive passing of one movement to another movement. For example, in photography, the Pictorialist movement which prevailed from the late 19th to the early 20th century, transitioned to the Modernist movement starting around 1930-1940 when some of its most notable practitioners started adopting Modernist tenets. Among them were Alfred Stieglitz and Ansel Adams whose early work was based on Pictorialist tenets and whose later work followed Modernist concepts.

What is interesting is that today both Stieglitz and Adams are known for their Modernist work, not their Pictorial work. In fact, their Pictorial work is often seen as a mistake or as an unsuccessful early attempt, as if the ebullience of youth had misguided their steps and led them in the wrong direction. It is as if this transition from one movement to another was not a transition but rather the emergence of their true artistic approach. Their embrace of a previous movement is forgotten. What is remembered is their adherence to a later movement. On a historical level, we remember artistic careers for the movement they ended with, not for the one they started with. On a personal level, we remember what is closest to us because it is more relevant to us.

It is my guess that today’s photographers who started with Modernism and later embraced Digital Imaging will be remembered not for their early work but for their later work. I believe this is because their later work is more relevant to the times they lived in and because this shift from one movement to another is perceived as progression and artistic development. It is seen as part of the process of finding their artistic way.

According to this version of history the true personality of an artist is defined by where they end up, not by where they started. This is true for the adoption of art movements and it is also true for the creation of personal styles, as we will see in my next essay: The Persistence of Style.

About Alain Briot

I create fine art photographs, teach workshops with Natalie and offer Mastery Tutorials on composition, image conversion, optimization, printing, business, and marketing. I am the author of Mastering Landscape Photography, Mastering Photographic Composition, Creativity and Personal Style, Marketing Fine Art Photography, and How Photographs are Sold. All 4 books are available in eBook format on our website at this link. Free samples are available so you can see the quality of these books for yourself.

You can find more information about our workshops, photographs, writings, and tutorials as well as subscribe to our Free Monthly Newsletter on our website. You will receive 40 free eBooks when you subscribe.

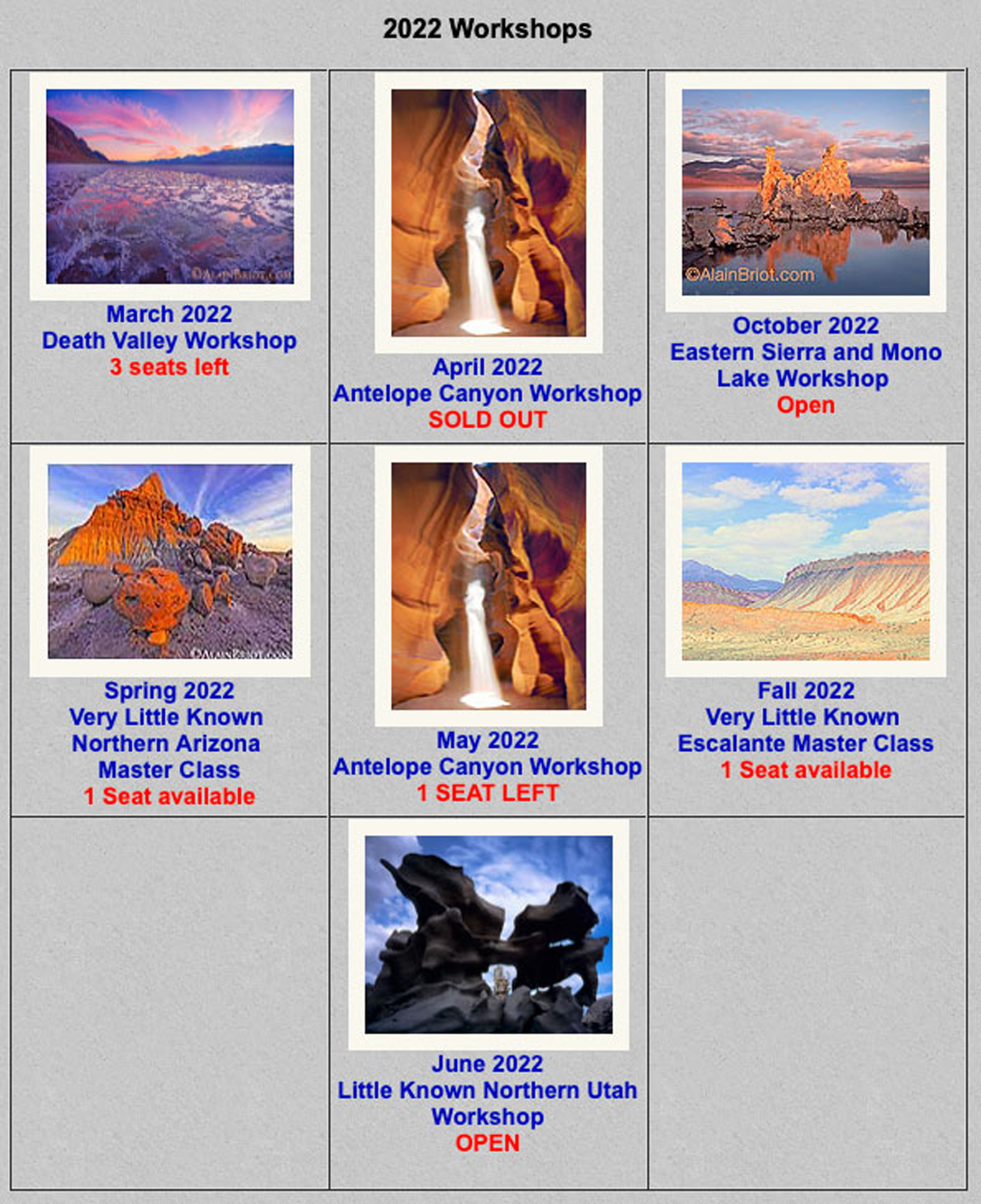

Studying Fine Art Photography With Alain and Natalie Briot

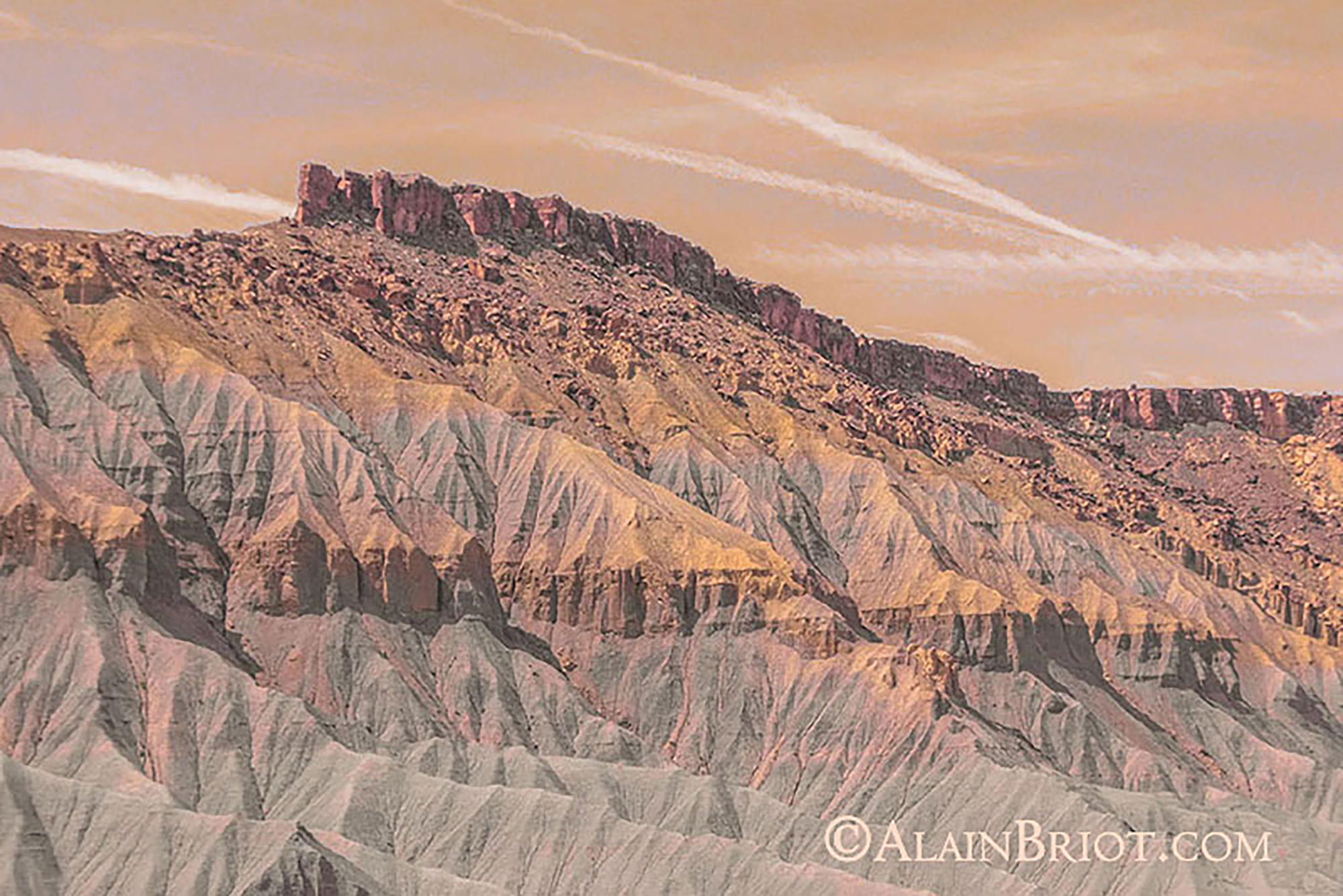

If you enjoyed this essay you will enjoy attending a workshop with us. I lead workshops with my wife Natalie to the most photogenic locations in the US Southwest. Our workshops focus on the artistic aspects of photography. While we do teach technique, we do so for the purpose of creating artistic photographs. Our goal is to help you create photographs that you will be proud of and that will be unique to you. The locations we photograph include Navajoland, Antelope Canyon, Monument Valley, Zion, the Grand Canyon and many others. Our workshops listing is available at this link.

Alain Briot

September 2021

Glendale, Arizona

Author of Mastering Landscape Photography,Mastering Composition, Creativity and Personal Style, Marketing Fine Art Photography, and How Photographs are Sold. http://www.beautiful-landscape.com [email protected]