History of Photography – Gertrude Käsebier

I am fascinated by photographic portraits. Our big brains devote huge amounts of resource to “reading” the faces of our fellow humans. We have an almost magical ability to guess how someone feels, what they are thinking, merely by glancing at their face. Not to suggest, of course, that we always get it right! But, we get it pretty close to right an amazing amount of the time.

A photograph of a person gives us enough detail, and it’s true enough, to give our big brains something to work on. We see a good portrait, and we can often imagine what the subject was feeling, thinking. Of course, it’s not quite true, the photograph is just an instant in time, perhaps an accident of expression, nothing like observing a living person in real time. Still, we feel that some of the same intimacy, that same kind of almost psychic ability, that we feel with a living person. This, regardless of whether our guesses are true or not. In this way, it is completely unlike a painted or drawn portrait.

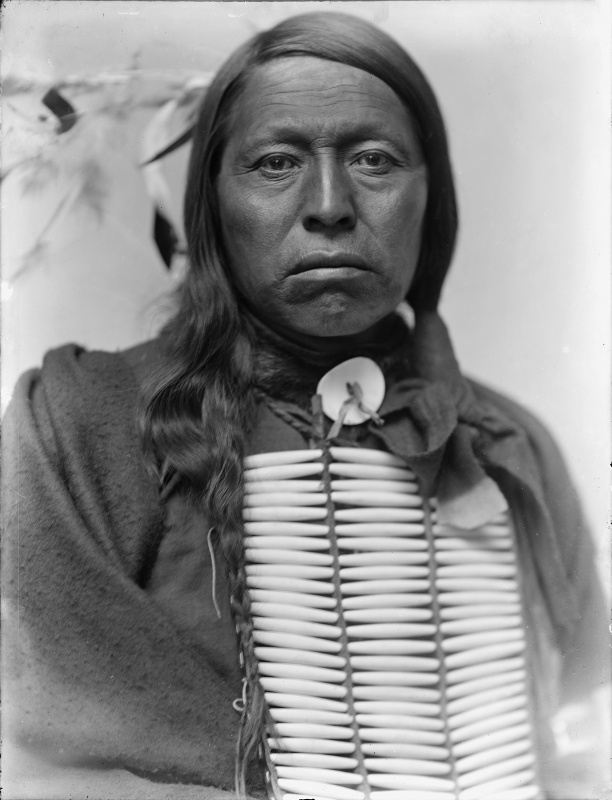

Gertrude Käsebier was one of the great portraitists working around the turn of the 19th century, an artistic and a commercial success at the same time. In 1898, near the beginning of her career, Käsebier photographed some of the Native American performers with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show. She took a humanist, and for the time somewhat unorthodox approach. Edward Curtis, working at around the same time, was developing ideas around a photographic record of the culture, and so focused on clothing, regalia, and other trappings. Some people see an unsavory sniffy of the noble savage in his pictures alongside his undeniably sympathetic viewpoint. Käsebier was interested in the individual character of people, and thus felt that her job was to reveal the individual character of the subject.

Accordingly, she shot Chief Iron Tail with no regalia whatever, and, perhaps more notably, did not discard the photograph of Chief Flying Hawk whose individuality so thoroughly dominates the frame.

It may seem peculiar to treat this notion of portraiture as special. Surely, after all, this is the entire point of a portrait? Well, not quite so. In prior generations, painted portraits were as often about the possessions and social stature of the sitter as about anything else. Indeed, even today, the Senior Portrait session so beloved of retail photographers is as much about the guitar, the boots, the car, as it is about the awkward near-adult being photographed.

This idea of revealing true personality, while probably not new (what truly is, after all) reaches new heights with photography, and Käsebier is in the van of the change.

After the Native American pictures, Käesebier aligned with Stieglitz, and her work appeared for a little while in the fabled Camera Work publication helmed by Stieglitz. Her later embrace commercial success apparently led to a falling out with the purist Stieglitz, and in the same general interval she entered the artistic orbit of Clarence White.

I think it is instructive to compare Käsebier with the earlier portaitist Julia Margaret Cameron. The latter used wet plates, with their inherent long exposure times measured in seconds, or occasionally minutes. Käesebier, in contrast, used faster dry plates. While dry plates are still ludicrously slow by modern standards (ASA 2 or thereabouts) they are faster than wet plate.

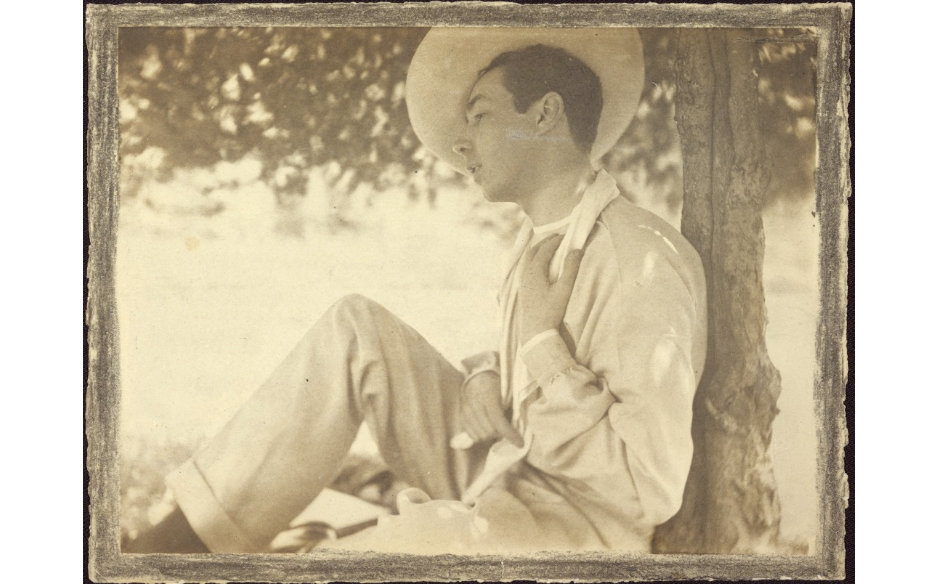

Looking at Käsebier’s portraits after Cameron’s, a sense of immediacy jumps out at you. There are genuine expressions present, a glare, a quirked smile, a glance. The faces are essentially mobile, rather than static, at rest. While these photographs are still leagues from the “instant photography” soon to come, it is beginning to have that instantaneous character which we take for granted today.

Both portraitists are still forced to pose their subjects, the exposure times are not really suited to any sort of candid photography (nor is an 8×10 glass plate camera, whether wet or dry). Cameron’s portraits capture the likeness of the subject, and perhaps something of the personality (at least, we can believe it) but nothing of the “moment,” whereas Käesebier’s photographs capture not only the likeness but also the “moment,” those brief expressions from which we glean so much about a person.

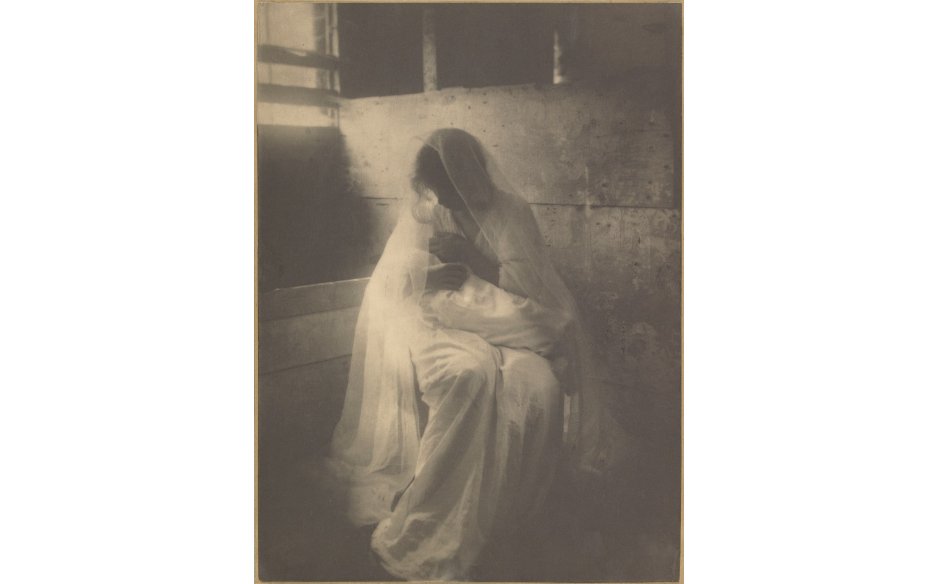

This is not to say that Käesebier was immune to Pictorial mawkishness.

She is a transitional character, at a time of transition.

Still, she is an exemplar of the ways in which increasingly sensitive emulsions, a mere technical detail, continued to fundamentally change the very nature of photography.

Andrew Molitor

September 2019

Bellingham, WA

Andrew is an ex-mathematician, ex-software engineer, full-time-dad. Sometimes he takes pictures, and sometimes he writes about pictures, and he's always got opinions.