Following an Inner Path – Colin Prior

We all know, instinctively, when we see a great photograph, but to become a great photographer takes a great deal more than that. Call it talent or vision or a combination of the two, manifesting itself in a subject about which an artist is passionate. If there is no passion at the outset between the photographer and her or his subject, then we are very unlikely to be moved. The other aspect worthy of consideration is how much depth there is to the work which is directly proportional to the amount of time the artist has invested into the project and increasingly, this quality is largely absent from much of the work I see today.

The reasons for this are not difficult to see: the currency of photography has been devalued and no one is investing in photography in the way that they once did. Few magazines, have the circulation to put money behind big photographic projects, brands are largely focussed on video production for visual communication and publishers are being extremely cautious about the type of projects they are prepared to invest in. The bottom line is that depth takes time and time takes money and for many working professionals, myself included, it takes a certain level of discipline, to ensure that you are continually investing in your own vision and creativity, otherwise you end up living other peoples’ dreams and not your own.

Throughout my career, I have managed to fund my personal work on the back of a commercial photography and publishing business, but the demands that this puts on my time are enormous. As a creative artist, I really don’t have a choice – I need to work to live, but my ambition in life has always been self-fulfilment. Despite the fact that images are now largely consumed on screens, I continue to believe that as photographers, it is imperative for our work to be published. A book remains the most authoritative way to showcase your work to the general public, and perhaps internationally. What most artists seek, above all else, is recognition for our work, although money is pretty good too! If you can attract a mainstream publisher this is always going to be your best route to marketplace. They have the editorial expertise, importantly, the distribution and the publicists which the marketplace demands. Whilst many photographers are successfully self-publishing books, they only get to sell to the choir and not the congregation and there is also the kudos that comes with the association of being published by an established publishing brand.

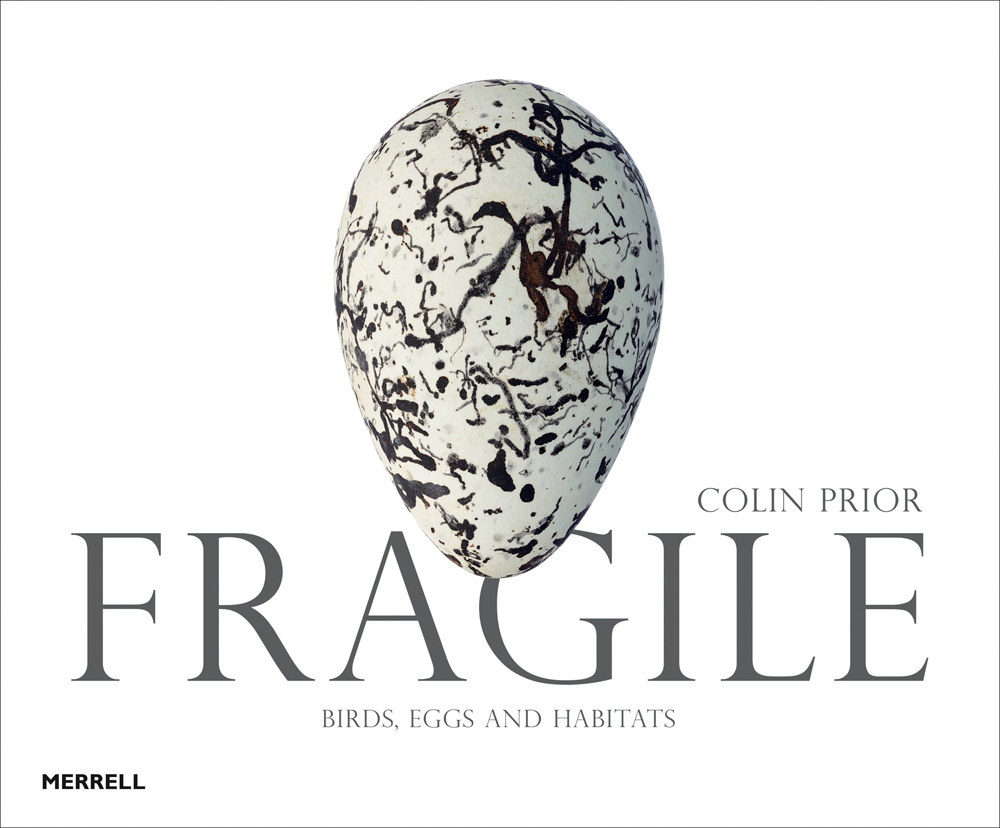

Returning to the subject of passion, over my 38 years as a professional photographer, I have published nine books – seven with Constable and more recently, two with Merrell and it is about these two most recent projects that I would like to discuss. The first, entitled Fragile, was published in September 2020 and is the culmination of ten years work. Having spent much of my time photographing landscapes in the Scottish Highlands with a Fuji GX617, I reached a point where I found that the panoramic format had become a bit of a creative straight-jacket and I knew it was time for me to hunt new game. Despite my first love being birds, I concluded in the earlier years of my career that I could say more about the way I felt about the natural world through the medium of landscape photography rather than by photographing wildlife. For me the opportunity to disassemble the elements of a landscape in my mind and then reassemble them through my viewfinder, in accordance with the way I felt, was infinitely more rewarding for me, than attempting to capture wildlife, where so often, the actions of what the animal does, in an instance, is the difference between a great image and a mediocre one. So, I began to think how I might fuse my passion for birds with that of the landscape but without having to photograph them – I felt that there were so many well established and excellent bird photographers out there already, that there was little I could do on that front that was new.

Since childhood, my life had been enriched by the birds I encountered on my sojourns and over time, I became increasingly conscious of their diminishing numbers or in some places, their complete absence. Many may be all too familiar to you – lapwing, curlew, moorhen, song thrush, kestrel, skylark, swallow, swift, largely missing from their former ranges and I began to think about how I might visually interpret this, without the need to photograph birds themselves. If I was hoping to attract the attention of the public in an effort to raise awareness of what I had witnessed, first hand, I would need to come up with something that they hadn’t seen before and to which they would instinctively be drawn.

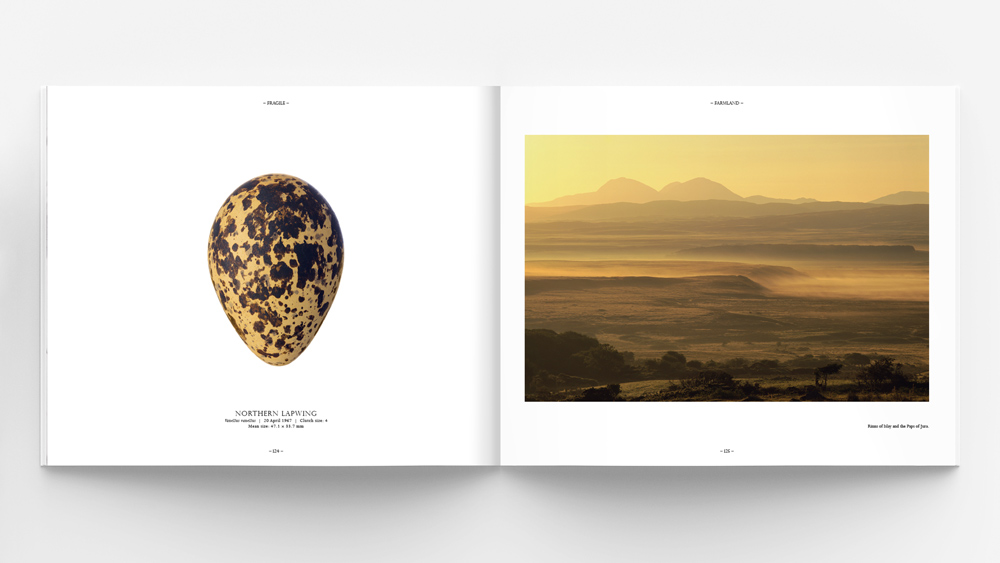

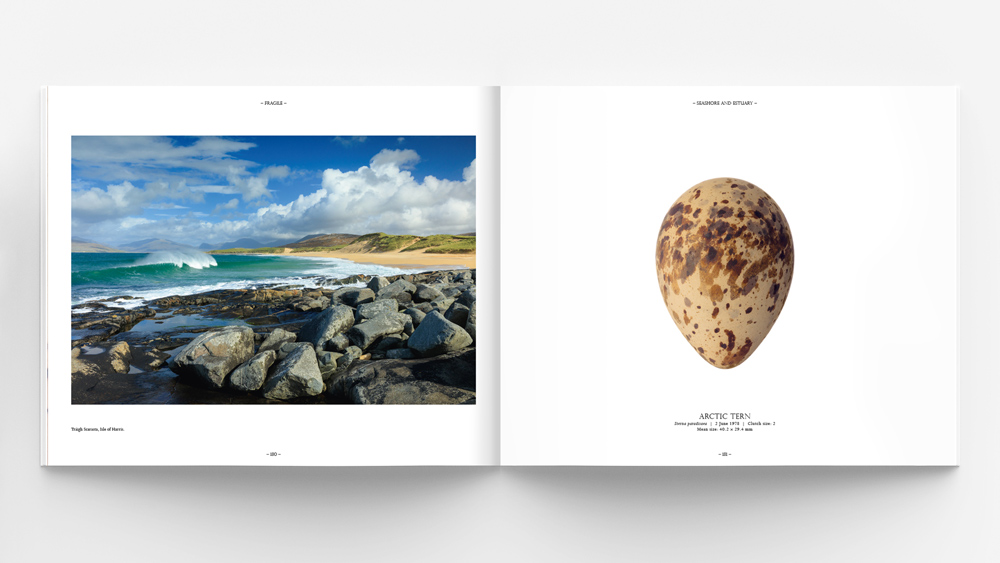

The idea for Fragile had been fermenting in my mind for many years – I could see it all clearly in my mind’s eye. I favoured the idea of creating diptychs; a spread showing two photographs together; one, an image of a bird’s egg, the other of its habitat – essentially, two disparate images and yet related on several levels. My criteria for the habitats were based on each eggs’ dominant colour, as I wanted to create a visual synergy between egg and habitat and in some cases, this meant revisiting certain locations at different times of the year.

I was aware that some of the museums had large collections of birds’ eggs bequeathed by collectors who had mostly been active in the early part of the 20th Century. Some of these eggs are exquisite, displaying the most beautiful combination of colour, patterns and shapes. So, I contacted the National Museums Scotland in Edinburgh and gained permission to photograph their egg collections.

From the outset, I was aware of the technical challenges that I would need to overcome to photograph eggs in the way I envisaged. In order to ensure sharpness from the front to the back of each egg, I would need to employ focus-stacking (where multiple images of an egg are captured at fractionally different points of focus). Each of the eggs photographed in this book are a compilation of between 40 to 80 separate exposures and subsequently blended together into a single image in Helicon Focus. The final image shows the exquisite shape, colours and patterns of each egg in an almost three-dimensional rendition.

To achieve this would necessitate sourcing a programable focus-stacking device onto which both the camera and lens are clamped, and which would need to be supported above the egg. By adopting this approach, however, a major problem arises – the combined weight of camera, lens and stacking unit would be such that only the heaviest and most sturdy of studio tripods would be able to provide the necessary rigidity which this process would demand – and even then, I still had reservations. Then there was the issue of studio flash and the need to build a custom lighting table, specifically designed for shooting the eggs on a white background and finally, I would need to prove a lighting technique before setting up in the Museum of Scotland and that would mean moving the rig, in the first instance, into my own studio first. In time, and with the help of a colleague, Derek Rattray, who owned all the necessary equipment, we set up a studio in the Museums of Scotland in Edinburgh and spend five weeks photographing around 250 eggs.

The final challenge was to complete the photographs of each birds’ habitat, which I had been working on for many years and this required continual research and planning. Ultimately, the success of the diptychs hinged on a synergy between egg and habitat, which was determined by the dominant colour of each egg. This necessitated travelling to a typical habitat, at a certain time of the year, to ensure that the tonal qualities of the landscape closely resembled those of the egg. When the egg and habitat images come together successfully, the result is symbiotic – one gives value to the other and vice versa. Retrospectively, I feel that the project has breathed new life into the eggs – the process of taking them from the darkness of the museum’s storage cabinets and bringing them into the light has, for me, been deeply rewarding – perhaps an atonement for the sins of the past?

Four decades of photographing landscapes have instilled in me an even deeper respect for the natural world and this book is an exploration of how the links between people, birds and their habitats have changed over time.

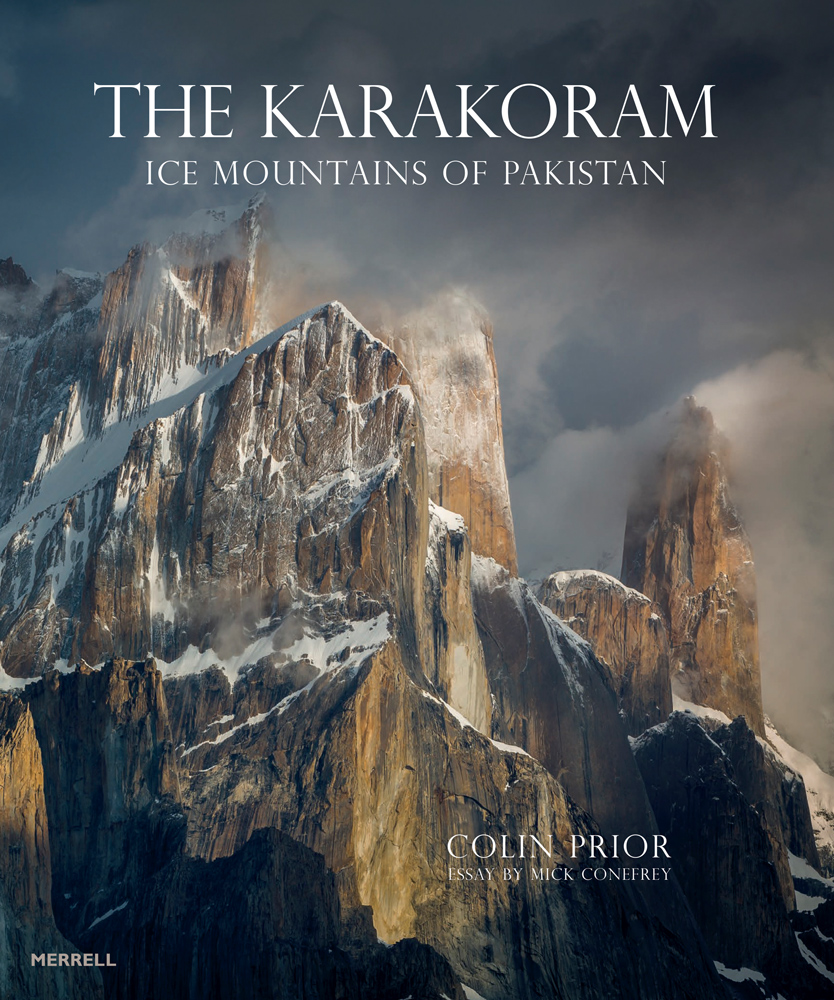

The second book, published in March 2021, The Karakoram, Ice Mountains of Pakistan, is the fruition of six expeditions over two decades and whilst I am elated to see the book finally in print, I am a little melancholy in the knowledge that another chapter in my life has come to an end. As I reflect, I am aware of the unique privilege it has been to venture out onto these remote glaciers with a small team of porters, much in the same way that the late nineteenth century explorers did as they surveyed these glaciers for the first time in 1892. From leaving the gateway village of Askole for the Biafo Glacier, there is no further contact with other humans, outwith our group until our return – something so rare anywhere in the world today and particularly where there is such mountain grandeur.

My fascination with the Karakoram Mountains began when I was twenty-three years old. In the travel section of my local library, I came across a book that was to change the course of my life. Written by the climber and photographer Galen Rowell, In the Throne Room of the Mountains Gods (1977) documented the 1975 American expedition to K2. I was familiar with K2, but had never heard of the Karakoram Mountains, and one photograph in particular, of the Trango Towers, captured my imagination like no other photograph ever had. What sort of place, I wondered, gave rise to mountains of this character, one that could transpose the mind to another realm? From that moment on, I was entranced and knew that my destiny lay there. It was not a question of choosing the Karakoram Mountains; they chose me.

For those not familiar with the Karakoram Mountains, they are all situated in northern Pakistan in the Gilgit-Baltistan region, and the range contains four of the world’s fourteen 8000-metre (26,247-ft) peaks (including K2), more than sixty peaks above 7000 metres (22,966 ft) and hundreds of spectacular rock and ice mountains over 6000 metres (19,685 ft) tall. Composed of granites and gneisses and sculpted by wind and ice into monumental spires, towers, cathedrals and pyramids, these rocks are a showcase of natural design and form.

I made my first trip there in 1996 on a commission for British Airways and it left an indelible impression in my mind. I was already familiar with the photographic ‘treasures’ that lay within the region of which I had only scratched the surface and eventually returned in 2004. The challenges associated with running and growing a commercial photographic and publishing business were not conducive to month-long excursions, to one of the remotest parts of the planet and where communication was by satellite phone only. However, I was determined to create a body of work there and realised that the only way that I was going to achieve this was with commercial sponsorship. So, I commissioned a copy writer and published an eight-page brochure, which I subsequently mailed out to photographic and outdoor brands. I called them, I spoke with their PR agencies and I visited them at exhibitions and in the course of time, I managed to attract three brands who supported me financially for a four-year period.

Please visit Colin Prior’s Website

In today’s world, even a pre-Covid one, this would now be unthinkable – there simply isn’t the budgets to support the efforts of an individual photographer in some remote part of the world. What has also changed in this short time is that if brands were considering supporting such a venture, the emphasis would now be on a producing a film and not simply stills and that would be a very different proposition. Ultimately, there has been a paradigm shift in the imaging world between 2012 and the present time where still photography has slowly been eclipsed by the moving image. It is not a change I relish – personally, I have no interest in producing moving content and it is not the reason I chose to become a photographer – it was the parallel with drawing and painting and a desire to produce images in the two-dimensional world of photography with the final expression in print that always appealed to me.

During the expeditions of 1996 and 2004, I worked with a variety of film cameras, including an Ebony 5×4, a Fuji GX617 and a Hasselblad XPan II. Compared to the weight and bulk of that used by my predecessors in the early twentieth century, this equipment made my undertaking to capture the mountain range a far less daunting prospect. Taking the 5×4 system with me was quite deliberate as I wanted to create a conduit with the past and allowed me to experience some of the challenges photographers like Vittorio Sella (who accompanied the Duke of Abruzzi to the Karakoram Mountains on his famous 1909 expedition) was confronted by. Sella had commissioned the London based company, J.H. Dallmeyer to make him a mahogany camera capable of exposing glass plates 40 × 30 cm (16 × 12 in.) in size. Prints made from negatives of this size reveal superb detail and clarity when enlargements are made, which smaller-format cameras were unable to rival. When I consider the ease and simplicity of using high-resolution digital cameras today, I wonder what the earlier photographers would have made of this new technology and its simplicity of use.

One of the biggest challenges for photographers working at altitude is the predominance of two colours – blue and white and regardless of the drama created by the mountains themselves, the repetition of white mountains and blue skies can create monotony in the pages of any book. I have witnessed this time and time again in so many mountaineering books and was determined not to create yet another. The Karakoram Mountains are a vertical landscape and the upshot of this is that the spires and towers naturally shed much of the snow they receive, so instead of large white masses that are so characteristic of the Himalayas, the Karakoram have large areas of exposed rock with snow lying on ridges. Accordingly, it is a paradise for black and white photography – powerful vertical graphics in myriad shapes, with lots of tonality in the granite rocks. I predominantly shot images best suited to reproduction in B+W, apart from situations where vibrant colours were encountered – this juxtaposition, I believe, is crucial to help the flow of a book. I would normally shoot what I refer to as ‘intimate landscapes’ which are essentially details from within the landscape and the mind maps these images very differently from the way it reads a view. The problem is that in the Karakoram Mountains the opportunities to capture this type of image are rare, so I am depending on the relationship between colour and black and white images to help the chapters flow and to keep the viewer stoked!

When I look at this book now it triggers many emotions and adventures over so many years, however it is still with a sense of incredulity that I consider how little has been published of this region given the visual drama of the Karakoram Mountains. I also can’t help thinking, that given the funding that was essential for the creation of this project and the with direction in which photography has moved, will there ever be another? It is with a certain sense of nostalgia that I close this piece and it is more than just the closing of another chapter in my life, it is the closing of a way of life which sadly includes photography as we have known it and regrettably, in time, the printed book.

I would like to thank my sponsors, Mountain Equipment, Lowepro and Lee Filters for funding this project and for the opportunity to fulfill a dream. I would also like to thank Zafar Iqbal owner of Baltistan Tours and my team of porters; in particular Karim and Hussein whose help and knowledge was crucial to my success.

Please visit Colin Prior’s Website

Colin Prior

December 2020

Glasgow, South Lanarkshire

ABOUT In a career spanning thirty-eight years, Colin Prior photographs capture sublime moments of light and land, which are the result of meticulous planning and preparation and often take years to achieve. Prior is a photographer who seeks out patterns in the landscape and the hidden links between reality and the imagination. He has produced nine books that include, The World’s Wild Places and Living Tribes, which were published internationally and has just completed a seven year project in Pakistan’s Karakoram Mountains. His most recent project, Fragile explores the links between birds, eggs and their habitats and will be published in September 2020 by Merrell. Colin has been the subject of three BBC documentaries entitled Mountain Man is Patrons Ambassador for the RSPB. BOOKS Karakoram | 2021 | ISBN 978-1-85894-687-0 Fragile | 2020 | ISBN 978-1-85894-688-7 Scotland’s Finest Landscapes | 2014 | ISBN 9781472111166 High Light | 2010 | ISBN 9781849013857 The World’s Wild Places | 2006, ISBN 9781845293505 Highland Wilderness | 2004 | ISBN 9781845290658 Living Tribes | 2003 | ISBN 9781552977460 Scotland The Wild Places | 2001 | ISBN 9781841193151 Highland Wilderness | 1993 | ISBN 9780094715608 AWARDS National Adventure Awards, Winner Business Category, 2015 Scottish Award for Excellence in Mountain Culture, 2020